The Cadet Company was first recognised by the Staffordshire territorial army in December 1917, and continued doing drills and exercises until 1931 when the ministry of war discontinued it, ostensibly to replace it with a new organisation. This, however, did not materialise until 1942, when the ATC finally came into existence made up of sixty-nine boys who were a mixture of past and present members of the school.

The Cadet Company was first recognised by the Staffordshire territorial army in December 1917, and continued doing drills and exercises until 1931 when the ministry of war discontinued it, ostensibly to replace it with a new organisation. This, however, did not materialise until 1942, when the ATC finally came into existence made up of sixty-nine boys who were a mixture of past and present members of the school.

In the following year, 1943, a Flight of the 351 Squadron was formed. Frank Read was CO of the 351 Squadron ATC which met in a building near to the Ferry Bridge off Bond Street throughout the war. He was assisted by Ron Illingworth.

This was to go on to gain more proficiency badges than any other squadron in the Midlands region with over two hundred in all.

The picture shows BGS Cadets engaged in rifle shooting at Lee-on-Solent camp in 1944. Jim Mayger is lying second from left, while Harry Rothera is standing at the far left.

Both shared their Headquarters down by the end of the Ferry Bridge but in 1944, the school pupil population had reached 381 and out of necessity, the HQ became used for other school activities. First year pupils used it for morning assembly, some used it for PE. Les Simpson, himself a cadet, also recalls music lessons being held there with Dickie Starling.

Ex-Grammar school pupil, D.A. Richards was awarded the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) in 1945. K. Rodbourne and C.B. Douglas later added to this role of honour. In 1946, the headmaster of the school at the time, Harold Moodey, recorded in his Speech Day Report “the heights reached by the 351 Squadron during the war deserve permanent commendation in the school annals“.

Ex-Grammar school pupil, D.A. Richards was awarded the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) in 1945. K. Rodbourne and C.B. Douglas later added to this role of honour. In 1946, the headmaster of the school at the time, Harold Moodey, recorded in his Speech Day Report “the heights reached by the 351 Squadron during the war deserve permanent commendation in the school annals“.

In 1949, a unit of the Combined Cadet Force was formed. Under the competent command of Major D. Davies assisted by Captain Harry Smith, two masters who were both to have long association with the school right through until the Winshill days, the fifty original ATC cadets was swelled to over one hundred cadets by 1953. When Peter Boulter joined the staff as an English teacher in the 1950s, he served as a Pilot Officer in the CCF.

Some may remember the Basic exam followed by the Army Proficiency Certificate which in turn led to Certificate ‘A’ Parts I and II. Successful completion allowed a badge to be worn on the sleeve with pride and many Certificates, such as Bob Fletcher’s shown here, survive to this day. This certificate was presumed to indicate that the cadet was ready for a ‘call to arms’ should World War III ever start, and assuming the Enfield .303 was still in use. In fact, Certificate A’s were important to the cadet force because financial support came from the War Department and the size of each school’s budget was calculated by the percentage of cadets who passed Certificate A, Parts I and II.

In the early 1950s, David Hopkinson was an NCO in the Army section and remembers stripping, cleaning and reassembling rifles and Bren guns in H.Q. and learning some of the theory that was involved in being a cadet. The playground in the school was used for drill and there was a rifle range behind, at the side of the bike sheds. A small hole appeared one day in the wall of one of the two classrooms down the passage from the bike sheds and, though it was ‘hushed up’ at the time, it was later revealed to have been caused by a stray bullet!

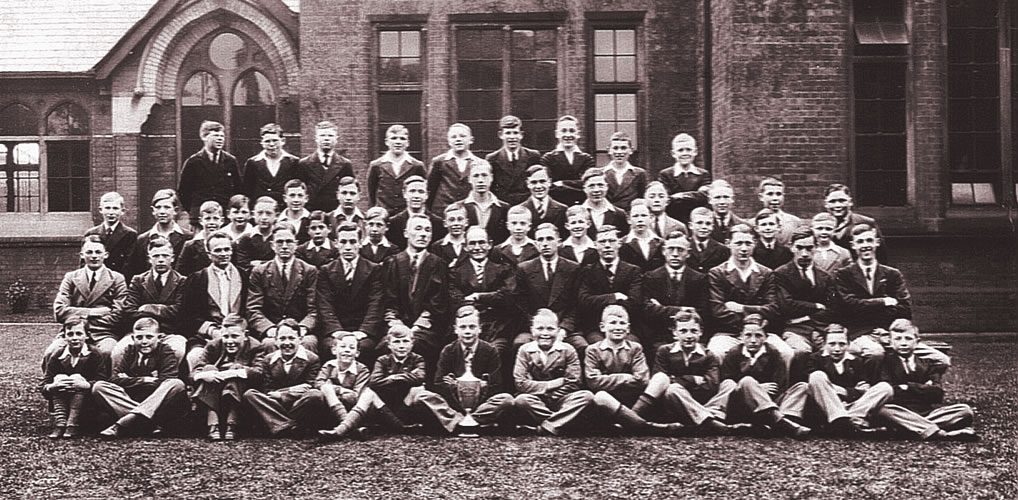

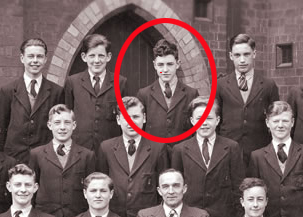

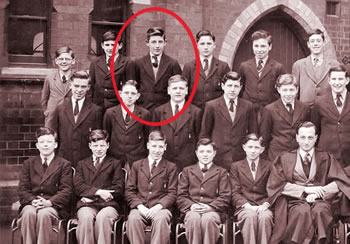

The below photo taken in 1952 shows only arond a quarter of the cadet membership of the time. There was still seperate Army and smaller Air Force sections. Only two Air Cadets can be seen here, with a different uniform and, conspicuous by his absence, is Bill Read who was their CO.

Partial group photo (from around 100 members) 1952

Partial group photo (from around 100 members) 1952

Back Row: Ward, Owen, Allis, Brian Hall, Alan Marshall, Langstone, Askey, Tony Butlin, Booth

Middle Row: Norman Lord, Bill Vernon, Newton, Geoffrey Salt, David Kirk, David Harper, M07, Mick Jordan

Front Row: Shorthose, Cooper, Williams, Sinclair, Major ‘Taffy’ Davies, Captain ‘Brab’ Smith, *Ted Ufton, Bailey, Shaw

* Ted Ufton, who went on to be a Lieutenant in the Royal Marines, was tragically killed in action during the Suez Crisis in 1956. Ufton had been an outstanding and very popular member of the school.

He was buried with full honours at Clayhall Royal Naval Cemetery. The headmaster, Mr. Pitchford, and Major Davies represented Burton Grammar School at his funeral and a plaque to his memory was erected in the school foyer.

His grave remains visited, the below photo taken in 2010 by his classmate Tony Prevett.

In 1957, the now CCF (Combined Cadet Force), having received a substancial sum under the direction of Colonel Scaife of the Staffordshire Territorials, acquired a new purpose built premises within the new Winshill Grammar School grounds which now included a Rifle Range.

Moving into the new premises was postponed for a while, together with the transfer of the school from Bond Street to Winshill after the roof blew off before the school was completed. The new CCF quarters were officially opened in 1958.

At this time, Harry ‘Brab’ Smith was no longer at the school (although he was soon to return at the request of the new Headmaster, Bill Gillion), and Major Davies became seriously ill and was no longer able to continue. This left Flight-Lieutenant Frank Read and a few NCOs to continue on their own. Added to this, with WWII ending some 13 years ago, the force did not really have the same relevance. By 1963, the ranks of the CCF fell below the minimum number required by the War Office and was closed.

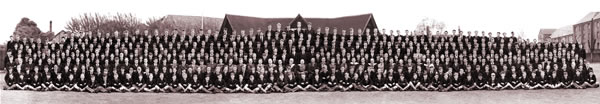

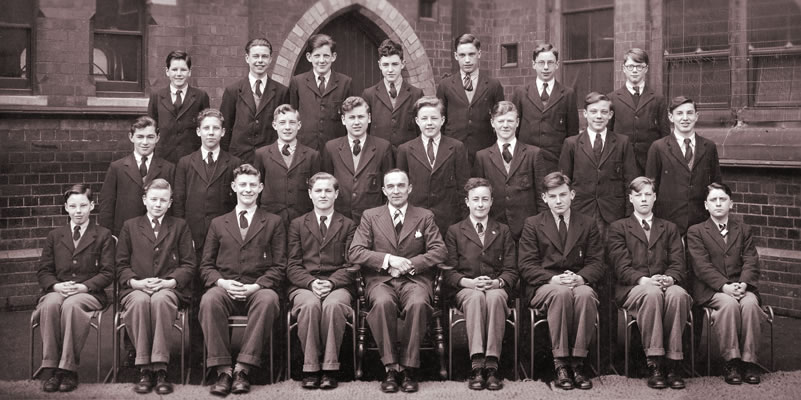

Group photo 1958

Group photo 1958

Back Row: John Gosling, D. Ball, John Slack, K. Redfern, Watson, Keith Humphries, Mellor, Dunn, T. Hill, T. Jones, Geoff Booth, T. Elks, John Cork

Middle Row: Quayle, D. Pritchard, D. Fletcher, R. Bucknall, Clowns, M. Tracey, M07, J. Birch, J. Buxton, Wadsworth, Rod Alexander, Graham Arnold, C. Freebury, S. Lawrie

Front Row: Smith, R. Hancey, A. Cloves, Yates, R. Fletcher, Flight-Lieutenant Frank Read, Major D.M. Davies, P. Boulter, Yarranton, M. Campbell, P. Rutland, Gilchrist, D. Shrubbs

Front: Woosnam-Savage, David Horsley, John Price, F04, E. Gillespie, A.D. Hughes

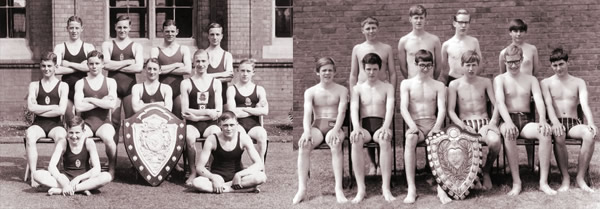

Group photo 1961

Group photo 1961

Back Row: B01, B02, Rod Moore, Griffin, B05, Terry Butler, B07, B08, Tim Hill, B10, Griffiths, B12, B13, B14, B15, B16

Third Row: T01, T02, T03, T04, T05, T06, T07, T08, T09, T10, T11, T12, T13, T14, T15, T16

Second Row: S01, S02, S03, David Liggins, Jim Roberts, S06, S07, S08, S09, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15

Front Row: F01, F02, Bob Bucknall, F04, Howard Ratcliffe, Charles Freebury, Ian Quayle, Flight-Lieutenant Frank Read, Major D.M. Davies, L.C. Rees (English), F11, John Price, Noel Poxon, F14, Robin Langton, John Goodhead

The following year, in an attempt to keep some pupil activity going, a new detachment of the ACF (Army Cadet Force) was formed and affiliated to the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

Captain John (Jack) Playll, seen on the far left in the above photo, was soon to join the school as a History teacher and was persuaded to take over the running of the cadets which he did with some success from 1966 to 1970. Perhaps most notably, in 1967, Seargant F.M. Airey and Corporal John Clark were both awarded Gold in Duke of Edinburgh’s Awards.

Captain John (Jack) Playll, seen on the far left in the above photo, was soon to join the school as a History teacher and was persuaded to take over the running of the cadets which he did with some success from 1966 to 1970. Perhaps most notably, in 1967, Seargant F.M. Airey and Corporal John Clark were both awarded Gold in Duke of Edinburgh’s Awards.

In 1968, Seargant F.M. Airey and Lance-Corprol F.C. Burrows were selected to train with the 16th/5th Queen’s Royal Lancers Regiment stationed in Germany, visiting camps in Hamburg, Celle, Hanover, Belsen and Luneburg. Sgt. F.M. Airey is pictured here in the top of a scout vehicle.

Finally, Sergeant J.E. Simnett received the Charles Black Shooting Trophy on belhalf of Burton Grammar School Troop.

Captain Playll (far left) was followed by a succession of officers, some of whom took the post with some reluctance. Although offering the chance for pupils to engage in such activities as canoeing, camping, rifle shooting, drill, weapon training, and fieldcraft, never really reaching its earlier heights as the relevance of training young men for the eventuality of future combat grew thankfully weaker.

In 1948 I was lucky enough to pass the 11-plus and win a place at Burton Boys’ Grammar School, becoming a “Grammar Grub” as such achievers were called. When I left Newhall School I still lived in Wood Lane but during the summer holidays we moved to High Street, Newhall. So new house, new school coincided. My parents were faced with a large bill to finance the purchase of all the accoutrements demanded by the school. I never did acquire all that was listed on the instruction sheet.

In 1948 I was lucky enough to pass the 11-plus and win a place at Burton Boys’ Grammar School, becoming a “Grammar Grub” as such achievers were called. When I left Newhall School I still lived in Wood Lane but during the summer holidays we moved to High Street, Newhall. So new house, new school coincided. My parents were faced with a large bill to finance the purchase of all the accoutrements demanded by the school. I never did acquire all that was listed on the instruction sheet. The food was provided by the School Meals Service and was delivered in metal canisters to the caretaker’s house some distance from the School Hall. Meals cost 5d a day when I first started but had shot up to 7d by the time I left. In current money this is 10p to 15p per week. You could, if you wished, take your own cold collation. At morning break a bun and a jam doughnut were on offer at the tuck shop on the opposite side of Bond Street. This was run by the Rawlings sisters, Lily and Gertie. The cost was 3d for two buns, 1d and 2d respectively; to buy them singly was a halypenny more each. The sisters were also unofficial school nurses, tending to minor injuries.

The food was provided by the School Meals Service and was delivered in metal canisters to the caretaker’s house some distance from the School Hall. Meals cost 5d a day when I first started but had shot up to 7d by the time I left. In current money this is 10p to 15p per week. You could, if you wished, take your own cold collation. At morning break a bun and a jam doughnut were on offer at the tuck shop on the opposite side of Bond Street. This was run by the Rawlings sisters, Lily and Gertie. The cost was 3d for two buns, 1d and 2d respectively; to buy them singly was a halypenny more each. The sisters were also unofficial school nurses, tending to minor injuries.

Life is punctuated by defining moments, how many defining moments we are allotted in life I have no idea, but do we recognise them when we experience them? Well, looking back on my life I can trace several, but at the time, they came and went without even registering a flicker on the Richter scale of defining moments. Apart from my birth being the first, the next must have been the year 1945, when as a 7 year old, the ending of the second world war was signalled by having a victory party held in the street where I lived, races were held, and during the 60 yard sprint I stumbled at a critical moment, it robbed me of victory my Uncle always told me. I only mention this, because 6 years of grinding war had passed me by almost unnoticed.

Life is punctuated by defining moments, how many defining moments we are allotted in life I have no idea, but do we recognise them when we experience them? Well, looking back on my life I can trace several, but at the time, they came and went without even registering a flicker on the Richter scale of defining moments. Apart from my birth being the first, the next must have been the year 1945, when as a 7 year old, the ending of the second world war was signalled by having a victory party held in the street where I lived, races were held, and during the 60 yard sprint I stumbled at a critical moment, it robbed me of victory my Uncle always told me. I only mention this, because 6 years of grinding war had passed me by almost unnoticed. The Cadet Company was first recognised by the Staffordshire territorial army in December 1917, and continued doing drills and exercises until 1931 when the ministry of war discontinued it, ostensibly to replace it with a new organisation. This, however, did not materialise until 1942, when the ATC finally came into existence made up of sixty-nine boys who were a mixture of past and present members of the school.

The Cadet Company was first recognised by the Staffordshire territorial army in December 1917, and continued doing drills and exercises until 1931 when the ministry of war discontinued it, ostensibly to replace it with a new organisation. This, however, did not materialise until 1942, when the ATC finally came into existence made up of sixty-nine boys who were a mixture of past and present members of the school. Ex-Grammar school pupil, D.A. Richards was awarded the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) in 1945. K. Rodbourne and C.B. Douglas later added to this role of honour. In 1946, the headmaster of the school at the time, Harold Moodey, recorded in his Speech Day Report “the heights reached by the 351 Squadron during the war deserve permanent commendation in the school annals“.

Ex-Grammar school pupil, D.A. Richards was awarded the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) in 1945. K. Rodbourne and C.B. Douglas later added to this role of honour. In 1946, the headmaster of the school at the time, Harold Moodey, recorded in his Speech Day Report “the heights reached by the 351 Squadron during the war deserve permanent commendation in the school annals“.

Captain John (Jack) Playll, seen on the far left in the above photo, was soon to join the school as a History teacher and was persuaded to take over the running of the cadets which he did with some success from 1966 to 1970. Perhaps most notably, in 1967, Seargant F.M. Airey and Corporal John Clark were both awarded Gold in Duke of Edinburgh’s Awards.

Captain John (Jack) Playll, seen on the far left in the above photo, was soon to join the school as a History teacher and was persuaded to take over the running of the cadets which he did with some success from 1966 to 1970. Perhaps most notably, in 1967, Seargant F.M. Airey and Corporal John Clark were both awarded Gold in Duke of Edinburgh’s Awards. All his life Beethoven was obsessed with this theme — the right of humanity to freedom and liberty, and it is to be found in many of his large scale works, notably the 3rd and 5th Symphonies. The overture is programmatic in design — the sombre opening bars which lead to a tense and agitated section portray the oppression of the Dutch and their struggle for freedom.

All his life Beethoven was obsessed with this theme — the right of humanity to freedom and liberty, and it is to be found in many of his large scale works, notably the 3rd and 5th Symphonies. The overture is programmatic in design — the sombre opening bars which lead to a tense and agitated section portray the oppression of the Dutch and their struggle for freedom.