The school was situated in Bond Street, a narrow side street off the Lichfield Street. It was an old-fashioned building with classrooms leading off a main hall. What had been the Headmaster’s house, on the corner of Lichfield Street and Bond Street had been taken over to provide some classrooms and accommodation for the caretaker (at that time a Mr Hudson). During my time 3 sets of semi-prefabricated classroom buildings were erected in the garden between the hall and the house; two were each made up of 2 classrooms (S & T and R & Q), the third was a new physics laboratory.

The school was situated in Bond Street, a narrow side street off the Lichfield Street. It was an old-fashioned building with classrooms leading off a main hall. What had been the Headmaster’s house, on the corner of Lichfield Street and Bond Street had been taken over to provide some classrooms and accommodation for the caretaker (at that time a Mr Hudson). During my time 3 sets of semi-prefabricated classroom buildings were erected in the garden between the hall and the house; two were each made up of 2 classrooms (S & T and R & Q), the third was a new physics laboratory.

The main door to the school was a heavy wooden door and led straight off Bond Street and, inside, up several steps into a small foyer and the corridor to the hall. The school office and Headmaster’s study was on the right of the foyer. Beyond the office a corridor on the right led to the cloakrooms, and if one turned left Room A, the home of the two Prep forms, was straight ahead with the staircase on the left again. At the top of the stairs a left turn and a few more steps would lead to the bookstore on the left, a classroom (J, which later became the staff room; previously they used the small room on the right of the stairs) straight ahead and to the right of this a large room which could be divided. The first part was equipped a normal classroom (L) but the rest was the Art Room. A right turn at the top of the stairs led one along the corridor to the Biology laboratory that was over the cloakrooms. As one walked along the corridor one could study the photographs of distinguished old boys and long school group photographs that hung on the walls. The Old Boy whose picture was at the top of the stairs was Admiral John Jervis, Earl St.Vincent, but it was more fascinating to try to recognise people in the old school groups, especially the current members of staff.

Not until one was a prefect in the VIth was one allowed to enter the school by the front door! The way in for the ‘lower orders’ was a gate a few yards further along Bond Street. Opposite this gate, on the other (south) side of the street was the Tuck Shop where we could buy sweets and drinks at break time. The gate opened onto a short passage, on the right was the single storey Woodwork room, on the left the door into the cloakroom and straight ahead was the tarmacked yard. A door on the far left of the yard led into the back of the hall, the toilets were in an outbuilding at the far end and the bicycle sheds to the right. Under one of the bicycle sheds there had been a rifle range.

The yard was the place where we congregated in the morning waiting for the bell for us to line up by form. There was a duty master and he was assisted by the prefects who fussed around the lines. When ready the forms went into school one-by-one, clearly a plan aimed at avoiding chaos in the cloakroom. Mid-morning break and lunchtime would see us in the yard once more. Various groups would huddle together and sometimes a fight ‘a scrap’ would break out and an audience would gather round to watch. More often than not the antagonists would come from the same small number of toughs. Sometimes it would be a case of bullying, but often the fight just sprung up from an argument. Sooner or later a member of staff would be alerted and come to stop the mêlée, sending the boys involved to see the Head. Mr Parkin, Tom Parkin, the Second Master or deputy head was a severe man who definitely had an aura. On occasion he would come into the yard and just stand at the entrance. For a while the noisy activity would carry on as ever but, slowly, the noise would die down as one group after another would became aware of his presence and eventually all would be dead quiet without him saying a word.

When I started at the Grammar School in autumn 1941, the Headmaster was Mr W.Fraser. However, he died after I had been at the school for only a short while so I don’t recall much about him and he had little influence on my time there. After an interregnum when Tom Parkin deputised, Mr Henry Stephen Moodey was appointed as the new Head. I believe he was 44 when he joined the school, though my recollection is of someone looking much older. He had a dark, heavy, face and appeared to scowl. My memory of him is coloured by later events, but I think he ran the school quite well.

Many of the men teachers had been called-up into the Services and the mistress in charge of Prep I, where I started, was a young lady called Miss Katy Duncan. Apart from nightly homework we were also given things to do during the holidays; Katy Duncan set us to read ‘The White Company’ by Conan Doyle.

Sometimes Mr Moodey took us for a period, whether he was filling in for an absentee or keeping his hand in and giving us some general education by encouraging us to think. During one such lesson period he asked us ‘What word do you always spell wrongly?’ There must have been some suggestions, but no answer satisfied him and he wrote on the board, W-R-O-N-G-L-Y! That was typical of him.

We had Woodwork lessons. Mr Jenkins taught us for a short while until he left (I assumed he had been called-up, but I understand he went to another school). Woodwork teaching was taken over by a newcomer to the staff, one ‘Tweak’ Hearn. He earned his nickname from his habit of coming up behind boys and taking some of the hairs on the back of their necks in his fingers and giving a sharp pull. His claim to fame was the car he drove to school each day. It was a small 3 wheeler – the single wheel was at the back, as far as I can remember. Such vehicles were based on motorcycle engines and so were economical on fuel. Wood was not easy to come by and second hand material was collected. I think our group only had Woodwork classes for two years during which time we learned how to saw and plane wood to make an accurate rectangular block and to make simple lap joints. Apart from what I picked up from observation and later from books, these lessons provided me with the basics for all the subsequent D.I.Y that I have done!

I have forgotten who was the Prep II form master. After Prep II I moved into the first form of the school proper; at that time there were two streams and I found myself in Ia along with many of the boys I had known at primary school. The Ia form room (C) was the first on the right along the corridor from the foyer to the hall. The form mistress that year was Miss Hilda Press but the room was really the domain of Mr H.H.Pitchford, ‘Horace’, and as he was senior History master, three walls of the room supported a time chart. To the best of my recollection there were 5 double rows of desks and for most of the year mine was in the second row near the back of the room. The subject of History, as I recall it, took us from Roman times to 1914 as we progressed from the Prep forms to IVa when we took the School Certificate exam.

The Prep forms curriculum was English, History, Geography, Maths, Art and Handicrafts (Woodwork). We began Physics and French in Ia. The first French teacher was Miss Hilda Press but I cannot recall who took us for Physics. Tom Parkin, the senior Physics Master, took us in IIa. The Physics Laboratory was at the back of the hall. It was typical of such labs in all schools and we sat on high stools at the benches, even for the theory lessons. The first experiment was the boiling of water! The aim was to teach us to observe and keep a record of our observations in our notebooks. We measured specific gravity, with those special little bottles with a capillary plug. These could be filled and the surface of the plug wiped dry and, because of the very small volume of liquid contained in the capillary, an accurate volume obtained. We even carried out experiments involving mercury. The health hazards had not then been fully appreciated and I remember the silver globules running all over the place, not to be lost because mercury was expensive! The Physics lab room became pretty familiar since all physics lessons took place there until one of the new semi-prefabricated buildings took over.

One day in 1944 we were in the Physics lab listening to Tom Parkin when, sitting on a stool at the end of the first bench, I suddenly found myself swaying from side to side – I suppose everyone did. Once the movement stopped Tom Parkin continued his lesson – he wasn’t easily put off, and may have seen it as important not to create any anxiety by worrying about the cause. At the time we had no idea what had happened but we soon learnt that there had been an explosion at Fauld, near Hanbury, at an old gypsum quarry used to store munitions. It was said, wrongly I believe, that the Italian prisoners of war employed there had caused it. Whatever the cause, a number of people were killed at the site and there is still a crater there. The explosion was about 5 miles away and the effect on the town was visible in the displaced or toppled church steeples. I see from a later article in the Guardian newspaper that the date was 27 November.

It was in the Physics lab that I clearly remember sitting at the rear of the back bench discussing with some others our plans for a cycling holiday, probably when we were in the Vth form. There was also the time of School Certificate in the summer term of 1946-47 when the experiments for the Physics practical exam were set out on the benches. During the exam we had to attempt two or three different experiments. Whatever they were, there was a time set for each one after which one had to stop, whether finished or not, and move on to the next. A little like musical chairs!

When Tom Parkin retired his place was taken by Mr D.N.Shorthose, a rather lugubrious man. He earned the nickname ‘the big G’ ? during one lesson he held something in his hand, probably a piece of chalk, and said, “If I let go of this it will fall”. In our ignorance we thought this was just too obvious to need saying, but in fact he was trying to get us to think! Why did it fall and not stay in the same place? By this time the Physics lab was housed in one of the ‘temporary’ buildings that had been erected in the garden.

When the temporary classrooms were built the Head decided that a small patch of ground between them and the old building should be made into a rockery. He involved us (that is, we provided the labour) and explained how to arrange the blocks of stone so that they interlocked, like canal lock gates, and so could support the weight of the earth banked up behind them. He also showed us how to put pegs into the ground in order to establish level paving.

After Ia, the progression was IIa then IVa to Va in which year we took the School Certificate Examination after 4 years. The progression was similar to that in many grammar schools and there was no IIIa. (The B stream and later, after the 1944 Education Act, the C stream took 5 years.) We took 9 subjects for School Certificate, English language, English literature, History, Geography, French, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, and Biology or Latin. We were told we were not allowed to take more! Of course, the school timetable also included time for PT (physical training, as it was then called), Games (Rugby, Athletics, Cricket), Art and Divinity (RE).

At the beginning of an academic year each form would go to the classroom upstairs next to the Art Room and opposite a small room used as a bookstore. We would each be given the textbooks required for that year’s work. We were instructed to write our names inside the front cover and it was always fascinating to see who had had the book in previous years. We also had to take the books home where we could cover each of them with brown paper so that they would last longer. George Cooper, who seemed to be in charge of the store, showed us how to do this. There was quite a skill involved in making a good job of it (preferably without the use of sticky tape). At the end of the year the books were collected and if a book had been lost or damaged a charge would be added on to the bill for fees that your parents would receive (until 1944 BGS was one of the Endowed Schools – essentially a Direct Grant school – and those without a scholarship paid modest fees; after the Education Act it became a state grammar school). I think we were expected to provide our own dictionaries and bibles when we first started at the school.

We were also given exercise books for each subject. Usually, one of each was sufficient for the year but if one needed another, one had to visit the bookstore at a prescribed time – and show some proof of the need! These exercise books were colour-coded – red for Physics, dark green for Maths, light green for Biology, buff for Chemistry and, I think, Geography notebooks were also dark green but with alternate pages of plain cartridge paper for maps. It is possible that we also had books for practical Physics with lined pages interleaved with graph paper.

The Art Room itself was presided over by Mr E.T.Spooner (I am uncertain about his initials) who also ran the Art School in Waterloo Street, part of the Education set-up in Burton. We would sit at desks, arranged in a square, painting in watercolour a still life or, occasionally, something from memory. Some of those who were good at Art went to the Art School on Saturday mornings

Mr A.C. (‘Chazzer’) Brown taught Geography to the lower forms. He was a tall man with very large feet. He cycled to school, was involved in running the Cub Scouts, and later ran the United Nations Association in Burton. The senior Geography master was Ron Illingworth who took us from IIa. He was a man of few words and a disciplinarian with a sarcastic turn of phrase. You didn’t hurriedly step out of line in Ron’s lessons. The ‘Geography’ room was down a dark corridor at the back of the hall that led past the Physics lab to the Chemistry lab. At change of lesson periods the class due in the room had to line up along the left hand side of the corridor leaving room for the outgoing class to file past. Ron would stand by the door of his room supervising the exchange with his eagle eye. During lessons Ron would sit at his desk and put his feet up while we got on with some task he had set, or while he fired questions at us. The floor of the room was steeply raked so that the desks were in tiers, presumably so that everyone had a good view of any maps displayed. It was also equipped with a large globe of the world suspended from the ceiling so that it could be pulled down when needed. Occasionally other lessons were held in the Geography room and it was during an English lesson there that we studied sonnets and learnt about Iambic Pentameters; it must have been here that we read Wordsworth’s ‘On Westminster Bridge’. It’s funny what triggers the memory! I had to give up Geography when I moved to the VIth form because it could only be taken on the ‘Arts’ side. Ron Illingworth’s main claim to fame was his ability at cricket. It was said that Ron had played for Somerset, but we were given a demonstration of his talents each year when the School 1st XI played the Staff.

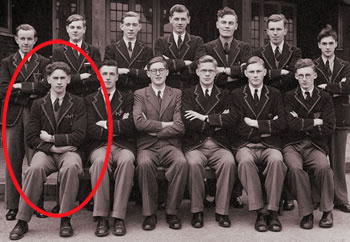

Mr G.L.‘Joey’ Daffern, as his nickname implies was a small thin man, and the subject of much teasing. He was our form master in IIa and also taught French and ‘Music Appreciation’, taking over the latter while Mr ‘Major’ Orchard was away during the war. The Music Room was a long thin room attached to the old headmaster’s house. Sometimes we would sing, sometimes listen (?) to him expound on some topic, and sometimes listen to him play the piano or a record. The occasion that has stuck in my memory was when he played to us ‘Morning’ from Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite. The other French teachers were Mr E.T.Ward and Mr Hugh Wood, the senior French master. Mr Ward was the IVa form master for the 1945-46 year. I recall little about French lessons except that Mr Ward played records of Jean Sablon, the renowned French popular singer, no doubt in the hope that our ears would become attuned to French accents. The song that sticks in the memory is ‘Le Fiacre’ all about a cab with the clip-clopping of horse’s hoofs. Quite soon after the war (1939-45) ended Mr Wood arranged summer holiday ‘exchanges’ to France for us with his contacts in Arras. Most of the boys travelled together (see the group photograph elsewhere on the website) but for some reason I wasn’t able to go at the same time. I followed later, travelling alone, and was given a large tag to pin to my coat so that I could be identified at Calais where a station official led me to the train and gave instructions about changing at an intermediate station.

For English the staff I remember were Mr Cyril Edlin and Mr J.K.‘Jake’ Hammond and later Mr Norman Cleave; at some point there was a Mr Potter. Cyril Edlin was a good actor and could use his face expressively in a way that I always associate with Alec Guinness; he also read poetry well. During English lessons we studied grammar, learning how to parse sentences, breaking them up into their different clauses. Each year we would read some fiction and we also read essays and poetry. Some of the authors I recall are E.V.Lucas, J.B.Priestley (the place ‘Bruddersford’ sticks in my memory) and Charles Lamb – who can forget the origins of roast pork?

Jake Hammond was a big man who was wont to shout at us. He also taught Latin when the original Latin master, Mr Jenkins was called up. Jake helped run ‘Games’, particularly Rugby, and the Scout troop. He must have taken my form for English when we were preparing for the School Certificate exam because we studied Milton ? ‘l’Allegro’, ‘Il Penseroso’ and ‘Lycidas’ ? with him. Mr Cleave returned to the school after his demobilisation from the forces too late for him to take me for English but he took what might be called ‘General Studies’ with the VIth . He took over the running of the Dramatic Society and produced several of the plays. He eventually became Senior Master before moving to be Head of Poole Grammar School.

The senior Mathematics master was Mr G.H.‘George’ Cooper, a tall man with slightly rounded shoulders and rather bushy black eyebrows who rubbed his hands together in a characteristic way which was often mimicked. He had been a pupil at the school before gaining a M.Sc. at Sheffield. For all of his time as a master he never married but lived with his mother, so it was quite a surprise when he married late in life; he had had to wait until his mother had died! His method of teaching us in the VIth form was to discuss a topic, writing the equations on the blackboard, explaining as he went along, and dictate notes. He made us number the pages of our notebooks and write an index to the topics. These books became our reference manual and I still have them and have often referred to them. I don’t remember using a textbook. After we had carefully transcribed his demonstration into our books he would give us problems to do which used the theorems. George also played the piano to accompany hymns at morning assembly.

The other Maths man was Mr C.F.L.Read. Frank Read, ‘Bill’ Read to the boys, was an Oxford graduate who also took some of the Games periods. He usually played scrumhalf for the staff in the annual game against the school 1st XV. He also ran the swimming. When he retired, long after I had left, he had completed 41 years at the school. In 1946-47 he ruled Va whose form room was above the library in the old Headmaster’s house.

I cannot recall who took us for Chemistry in IIa but our first experiment was to separate salt from sand; as salt is soluble it can be dissolved away leaving the sand – Q.E.D., as schoolboys might say! Mr E.C.Nicholson took us for Chemistry from IVa. ‘Nick’ was a small man and seemed to spend nearly all his time in the Chemistry lab; he was also form master for VI Science. I am sure he had lost his sense of smell after years of inhaling the various chemical vapours that enveloped the lab. We used retorts and condensers to purify solutions and learned how to test for different elements. Standard solutions were made up and titrations made using burettes to ascertain the strength of unknown solutions. The School Certificate practical exam included a number of such tests. In those days there were fewer regulations to hinder Chemistry lessons and we watched as hydrogen sulphide was made in Kipp’s apparatus and saw phosphorus and sodium react with air and water. Mr Norman Jones joined the staff to help with the Chemistry, and I believe some Physics, teaching, but he don’t think he took our group. Somehow we got to know his previous address in Pendlebury, Manchester. He was very puzzled when he received postcards at that address! Incidentally, he married Tony Morecroft’s sister.

When we moved from Ia to IIa, we had to make a choice between Latin and Biology. I chose Biology without too much hesitation but, at the lunch table, I learnt ‘amo, amas, amat, amamus, amamus, amant’ from other boys who had chosen Latin. The senior Biology master, Mr R.G.Neill, was serving in the forces and I cannot recall who took us in IIa. Eventually Mr Neill returned from serving in the Navy and taught us in IVa. His distinguishing feature was the way he walked. His body was turned so that his right shoulder always led the way! It was one of those characteristics that schoolboys pounce on to imitate. We decided that it was the result having to negotiate narrow passages during his naval service. After a while Neill left Burton to take a post in Cheltenham. He also became known as the author of a novel, ‘Mist over Pendle’, about the witchcraft in Lancashire around Pendle Hill and the secretive comings and goings of the Roman Catholics to the big houses there. Mr Moodey taught us for a while; he seemed to be able to cover for a wide range of subjects. During one of the lessons he took he pointed out that the hairs on our lower arms were angled towards the elbow. He folded his arms across his chest with the fingertips at shoulder level to illustrate how, in that position, the hairs pointed downwards. He suggested that the same was true for the apes and allowed them to shield themselves when it rained, as the water would be deflected away from their bodies.

Mrs E.Wain then took over Biology teaching. Her husband, H.J.Wain – an Old Boy – was a noted local naturalist. She made us learn the Greek and Latin terms used in biology. We learnt how to clean slides and other glassware with xylol that would evaporate so that one didn’t have to wipe it dry. We learnt about the make-up of plant and animal cells and tested potatoes for starch and protein using a variety of stains. Some of the work involved measuring rates of transpiration with tree branches we brought in. We also learnt about animals and their similarities, about Mendelian genetics, and reproduction. Our exercise books were duly illustrated with black and white rabbits! One year she took us to an old quarry near Bretby to study its natural history. Mrs Wain was succeeded by Mr Raymond Crowther, a younger man but who never looked particularly fit. He seemed to spend all his time in the biology lab preparing things or carrying out experiments.

I cannot recall all the members of staff during my time and I have forgotten even the names of some of those that taught me. I vaguely recall the name Dawson when I was in the lower school and Hilda Press was there for a while. Percy Barrett came later but never taught me. At some point Connie Walker joined the school and took us for Divinity; she had previously taught me in Primary School! ‘Gerty’ (or ‘Polly’) Lownds was also a substitute for the men serving in the forces. I think she probably taught Maths. When teachers were about to leave the school it was the practice for a collection to be made and at their last morning assembly a presentation would be made to them. ‘Gerty’ distinguished herself by reappearing in school the next term after such a presentation and being given a second leaving present after a year or so when she finally left.

Major Dai Davies rejoined the school after demobilisation and took up the PT classes as well as helping with Games; I cannot recall who took PT while he was away, possibly Jake Hammond. There would be at least one period a week for PT which we spent doing exercises in the hall. There was no gym; the hall had to be used for morning assembly, PT classes and as a dining room for school dinners! Occasionally we would be taken out into the yard for some fresh air. Sometimes there was work with ‘horses’ for vaulting and plank-like benches, which presumably tested our balance. At the end of each PT period the equipment was simply carried to one side of the hall. At some stage thick climbing ropes were installed and we were taught how to lock the rope between our feet so that we could climb to the top. These ropes were hung from a beam and when not in use had to be drawn to one side and attached to a hook in the wall. The much-improved facilities enjoyed by schools today are desirable, but they are not essential for a school to be successful.

The school did have a good playing field with a pavilion on the other side of Lichfield Street – five minutes, or less, walk away. It had been given by the Old Boy’s Association as a memorial to their fellows who had been killed during the 1914-18 war. Also, for some of my time, the school was able to use Peel Croft, the town rugby club’s field that was adjacent. There would be one afternoon each week allocated to ‘Games’ for a group of forms. Everyone took part, unless there was a medical reason and a boy had been excused (one had to bring a note from a parent). In winter the group would be divided into teams for rugby so there would be two or three separate games at one time. The better players would form an embryo school team and would receive most attention; the rest would have scrappier matches. There were House competitions each year. There were four houses, Clive, Drake, Nelson and Wellington. In order to field a house team nearly everyone had to play, whether they were any good or not. House matches usually took place on Saturday mornings.

Towards Easter everyone was made to take part in cross-country running. We would set off from the school field and follow a route down Bond Street, across the Ferry Bridge, through the Stapenhill Recreation Gardens, the ‘Rec’ – run up a road which led to the water tower, just off Ashby Road, then come back through the ‘Rec’ and over the bridge to base. Track and field athletics were also fitted in. The house competition involved, amongst other things, the accumulation of points by individuals according to what standard they achieved, and so everyone was involved. The standards would be a certain time for the various running races, a set height for the high jump and so on. Teams made up of the best in each house for various events would then compete on Sports Day. Apart from the house competition the best individuals stood the chance of being named ‘Victor Ludorum’.

Summer was the cricket season. Games days followed the same general pattern, the best cricketers would play with full equipment on the main field while the rest of us managed with whatever gear was left over – one bat, one pad and, if lucky, one glove etc. The school teams played against various other schools such as Denstone College, Repton School, King Edward VI Lichfield and Ashby Grammar School. There would be matches both at home and away throughout the season. Team lists were posted on the notice board in the hall and would be scanned avidly by the contenders for team positions. The Houses had separate notice boards but those being recruited for the inter-house matches were often less keen! When I was in the VIth form, I was asked to keep the score for the 1st XI cricket team. This suited me well as I didn’t have to take part in the normal scrappy games. As well as sitting in the school pavilion for the home matches on Wednesday or Saturday, I travelled with the teams for the away matches. We would always rate the school we visited by the sort of tea they provided and my recollection is that Denstone was pretty plain fare! One year we travelled all the way to RAF Cranwell, in Lincolnshire for a cricket match. It was while scoring for the team I first became aware of what seemed to be a magic writing instrument, the ‘Biro’, the first ballpoint pen when I was lent one.

Every year the masters challenged the school teams in both rugby and cricket matches; I guess they recognised that while they could offer weight and experience in these they had no chance in athletics! They gave no quarter in the rugby and, thanks to Ron Illingworth who was often ‘not out’, did well in the cricket.

Swimming was not overlooked either, though it probably only took place in the summer term. Each week we would be marched from school, through the water meadows, to the municipal baths that stood by the bridge over the river Trent. It must have taken 15-20 minutes to get there and the same to return, and then we had to change, so I suppose we must have been allocated a double period. We learnt to swim and dive, some of us better than others. Inter-school matches were arranged for the team and there was an annual ‘gala’ when the houses would compete. Those of us who were not taking part stood on the balcony to watch and, as ever in such surroundings, it was very noisy with sound reflecting from the water below and the glass roof above. Bill Read was the master I most associate with swimming and in my time the star swimmers were J.Hilton and Bill Mayger.

The school was, I suppose, a typical Grammar School. The discipline was strict but I never felt it oppressive. Most of the teaching was sound, if in some cases uninspiring, and it certainly provided an excellent foundation for whatever we did subsequently. Homework was set and marked regularly. At first at the end of each year, and later at the end of each term, there would be a report which usually gave our form position based on the term’s marks and, when appropriate, our exam position and a final position. Prizes were awarded for position in the form and in most of the individual subjects; some of them were named after the person who had endowed them: N.P.Allen (Physics), R.T.Robinson (Mathematics), Nellie Hatfield (Higher School Certificate), A.G.Appleby (Higher School Certificate). (Norman Allen FRS, an ‘Old Boy’, was at one time Director of the National Physical Laboratory; R.T. Robinson was a former Headmaster; I don’t know who the others were.) There would be a ‘Speech Day’ each year, presided over by the Chairman of the Governors, when the Head would present a report and an invited speaker would be asked to hand out the prizes. These events took place in the Town Hall. The staff, prefects and prizewinners would sit on the platform while the rest of the school and the parents would sit in the body of the hall. Some boys, such as Hugh Richmond, finished up with several prizes so the citation took some time! There was a ritual to these events. The Chairman of the Governors would invite the Head to present his report and this was followed by the presentation of the prizes. The recipients would step down from their seats at the rear of the platform, walk to the front on the right-hand side of the staff seats and pass in front of the presenter, returning on the other side. Everyone was carefully drilled beforehand to accept their prize(s) in their left hand so that their right hand would be free to shake hands. After the prizes had been given out the guest would make a speech, usually extolling the school or exhorting the leavers to ‘go out into the world’ and be good citizens. The boys always waited anxiously for the end of the homily because it was traditional for the speaker to call for the school to be given a half-day holiday! During the proceedings, the Prefects sat on the right hand side of the platform, with the Head Boy and his deputy at the front of the stage. When the proceedings were at an end, three of them, in turn, thrust their right hand into the air and called for ‘Three Cheers for The Speaker’, ‘Three Cheers for the Staff’ and ‘Three Cheers for the School’. I may not have remembered these exactly.

In the tradition of the Grammar School, a number of boys in the VIth form were appointed as Prefects. When appointed, prefects could add maroon and blue ribbon trim to their blazers and a tassel to their caps; all boys had to wear the school uniform of navy blue blazer and dark trousers (when I started the younger boys wore short trousers) and caps to school. The Prefects had a number of duties, some of which followed a rota. They would organise the separate forms into lines in the ‘yard’ ready to go into school at the beginning of the day. One would be Duty Prefect for the week. His main duty was to read the lesson at the morning assembly; he would stand by the door to the hall, behind the piano, and when the time came would come round in front of the piano, mount the platform and pass behind the Head to reach the lectern. It was always advisable to rehearse the reading beforehand! There were occasions when the choice of lesson was left to the reader but for the first assembly of each academic year it was traditional to read from Philippians (iv, 8) – ‘Whatsoever things are true … Think on these things’. After the reading the duty prefect would return to his station. Sometimes a boy would feel sick or feint and the duty prefect was expected to help him out to the cloakroom, though usually one of the staff would be on hand. There were other jobs too, I do not remember them all but I think one was to ring the bell at the beginning of morning and afternoon sessions, pulling on the rope which hung down at one side of the hall. Then there would be ‘dinner duty’. Another was to supervise a class when staff member was absent or called away for some reason, and so the Prefects were accorded a certain amount of authority to discipline boys.

It was the job of the Head Boy to work out the rota of duties. When I was a prefect (1948-49 & 1949-50) the Head Boys were Hugh Richmond followed by Dennis Grimsley. One day suddenly all the Prefects were summoned to take over all the forms. All we knew was that the staff had been called to an emergency meeting. After the meeting, Dennis was called to see the acting Head, Mr Pitchford who explained the situation to him. The cause of the emergency was that the Head, who had been away ill, had committed suicide by throwing himself in front of a train at Burton station. We weren’t told anymore and there was an air of mystery but we soon learnt that before killing himself Mr Moodey had brutally murdered his wife and two children.

Along with the duties, as Prefects, we were given certain privileges, for instance we could enter school through the main oak door. The main privilege was a room to ourselves, upstairs in the old headmaster’s house, so that we didn’t have to go to our form rooms at the start of the day. As well as shelves for our books there was a table-tennis table and this was well used. Dennis showed great skill!

There were other occasions for boys to take on responsibilities. Each form had a Form Captain elected by the form who would from time to time act as the spokesman for the form. As I have mentioned, the school was organised into houses, mainly for sports, each of which had to have a House Captain, House Secretary and Captains for the varies teams. There were also lunchtime duties. Trestle tables had to be erected in the hall. A senior boy would be made head of table and would be expected to keep order and supervise the putting up and taking down of the tables. There would be a ‘duty table’ each day (or each week, I forget which) and the head of table had to organise his group to do the chores.

In addition to the regular lessons, ‘English Essay’ and ‘English Speaking’ competitions were held each year for both junior and senior parts of the school. Although the competitions were open I think certain boys were encouraged to enter on the basis of their achievements in the normal course work. For the speaking, ‘qualifying’ rounds would be carried out during one of the lessons. Hugh Richmond was the star and usually carried off the prize. Even if we didn’t shine in this, when in the Vth and VIth forms, we could join the Dramatic Society and take part in the production of the annual play, either acting or helping behind the scenes. (This was always great fun and I have written about this separately.)

In my time, a period was set aside each week in the Vth and VIth forms for us gain more general experience and widen our horizons. The VIth form Society had been started by Tom Parkin in 1942; I think the Vth form Society was introduced when I reached that level and would take place during the last period of one afternoon. For the latter, ‘Bill’ Read, who was our form master, presided and each week someone would be asked to give a short talk or there would be a discussion. Over two or three sessions each of us would be called on in turn to give an unprepared five-minute talk on some subject; I think the topic was sprung on us but I may be wrong.

The VIth form Society was run more formally. All the forms, Upper and Lower, Science and Arts, would meet in the (new) Physics lab. I am sure minutes were kept and read at the next meeting in the proper way. Usually, there was an invited speaker. One boy would have to introduce the speaker, who would speak for ½ – ¾ hour, or perhaps a little longer, and at the end questions could be asked before finally another boy had to propose a vote of thanks. In the process we learnt how to conduct a meeting. The talks were obviously intended to inform us about life beyond school and, as far as I recall, were generally interesting. Why should I recall that one talk was about the use of reinforced concrete?

I’m not sure whether it was when we were in the Vth or VIth form, but one afternoon we went to the magistrates’ court housed in the domed, white stone building in Horninglow Street opposite the end of Guild Street. There a mock session of the court was enacted with a ‘volunteer’ playing the accused – my recollection is that Carey Hopkinson played that role. This was clearly aimed at showing us how society worked.

We were also encouraged to have interests outside our academic work. An annual Hobbies Exhibition was held. Boys were encouraged to enter something in one or other of the classes – Collecting, Model Making, Cooking, Art, and so on; entries ranged from a Kayak built at home to cakes. First, 2nd and 3rd Prizes were awarded for the best exhibit in each category.

There were school Cub and Scout Groups run by some of the masters – ‘Chazzer’ Brown looked after the Cubs and Jake Hammond the Scouts. We learnt about the Union Jack, knots, and several simple physical exercises, about keeping clean and tidy and would be awarded badges when the test was completed. Each year there was a national ‘Bob-a-Job Day’ when Cubs and Scouts carried out all manner of tasks in return for a standard payment of one shilling, whatever the task; of course, the donor could give more if they wished. This was an extension of the ‘good-deed-a-day’ credo of the movement and aimed at raising funds for the troop, perhaps for a charity though the time of sponsorship had not arrived then. One year the Cub pack was directed to cut the small lawn facing Lichfield Street of the old headmaster’s house, then occupied by the caretaker, Mr Hudson. All we had were several pairs of shears, most of the old type as I recall, so we spent a long time on hands and knees nibbling away at the grass

The same pattern of activities happened in the Scouts. Each year there would be a camp lasting a few days. Sometimes the troop went to Beaudesert Park on Cannock Chase. I was with a group that went to an estate at Rangemore, just outside Burton. We had to load kit onto a ‘trek’ cart and push it around. The camp was tented and cooking was done over an open fire. Some boys would be delegated for camp duty to tidy the site, keep the fire going and cook the meal. Learning to wield a felling-axe to cut down trees was one activity. Nearby in the Park there was a large pond (or small lake) in which we swam (in spite of the possibility of weeds) and on which we sailed a raft that we built. I doubt if that would be permitted today!

An opportunity to hone our social skills came when a dancing class was started while I was in the Vth form. It was held one day each week after school at the Girls’ High School. We boys would walk or cycle across town with our dancing shoes to join our female contemporaries. Millicent Simmonds, who ran a dancing school in the town, gave the instruction. We learnt all the ballroom dances, waltz, fox-trot, quickstep, tango, military two-step, valeta and so on. At the end of a session there would be a formal Ball.

A chance for the senior boys and staff to let their hair down came at the end of the autumn term when an ‘Upper School Social’ was held in the school hall. I first became aware of this when some of the lower forms were invited to watch a performance long before I was in the VIth. I remember that occasion because we were entertained by a jazz group formed by 6 or 7 of the senior boys; Bill Bennett played the clarinet, Gordon Bates, played either the clarinet or saxophone, and Tony Reynolds, the son of a local dance band leader played the drums, I think. For these events a stage had to be erected at the end of the hall. Trestles and boards were stored above the bike sheds and had to be brought into the hall to produce a platform that stretched from wall to wall; a ledge had been attached to the side walls to support the boards where a trestle couldn’t be placed. When in place the stage restricted access to the labs and end rooms as well as the passage of boys moving between lessons, but it was all in a good cause! A proscenium arch was created along one of the beams to carry the curtains and lights were attached to brackets on the walls. It was a small but quite usable stage. The know-how for building it was passed down from year to year so one felt very important when you were the one who knew how it all fitted together.

Contributions to the programme came from anyone willing to prepare something and the staff usually put on a ‘turn’. One year several of us decided to stage the sketch about trial of Guy Fawkes by the authors of ‘1066 and all that’, W.C.Sellar and R.J.Yeatman (The policeman played by Reg Hardwick presented his evidence with ‘On the night of the 5th inst. ….”; I cannot find the script, can anyone help?). The different parts were allocated and words learnt and we had to make costumes and other props. As far as I know it went down well. Then three of us, Reg Hardwick, Tony Morecroft and myself, tried our hand at song writing! We wrote words alluding to the school to fit the ‘Much-Binding-in-the-Marsh’ tune that featured in the Richard Murdoch and Kenneth Horne radio programme. We all worked on the composition – sometimes during a class! – and one Saturday met at Tony’s house finally to hone it into shape. I have never been able to sing so we asked Dennis Grimsley to join Tony and Reg for the performance. I can remember only a few words of one verse that went something like this -

At Bond Street Academy,

We have a GNUer car than any other.

At Bond Street Academy,

………

The Grammar School was in Bond Street and the physics master, Mr Shorthose, came in a car with the registration GNU. Tony tells me he can recall only the line -

At Bond Street Academy

there’s lots of boys and not much room to put them.

At Bond Street Academy,

……..

We think this refers to the additional pre-fab classrooms that were being built at the time in what remained of the garden. Dennis’s memory is better, although he can remember only the verse referring to a new man who had joined the staff from the Royal Navy, a Mr A.J.Corby who taught Physics. It went like this -

At Bond Street Academy,

We’ve got another master on our staff.

At Bond Street Academy,

He was neither in the Army or the RAF.

His discipline is pretty strict, on which he holds strong views,

and there are certain words that he’s forbidden us to use.

And phrases such as ‘Shut up, dry up’ are those we’re going to lose,

At Bond Street Academy.

(Does anyone remember any more?)

One year Fred Mallet acted as conductor of an ‘orchestra’, but although they had instruments they didn’t play a note. They mimed to music from Wagner’s ‘Lohengrin’ played on a gramophone behind the scenes. It was very good but I worried about Fred waving his arms about so energetically because I understood he was supposed to have a weak heart.

Another event was a quiz. There were two teams of two or three boys each and one of the staff acted as question master. One of the questions was, “Did it ever snow in North Africa?” The answer, of course, should be “Yes”; remember the Atlas Mountains. Another question was “What did the initial K in Mr J.K.Hammond’s name stand for?”. Whoever answered that slightly tricky question gave the right answer, K(ay). Because of they are homophones, I still don’t know whether his name was Kay or whether he simply had an initial K.

The staff contributed a sketch based on the Prefects. The stage was set to represent the Prefects’ Room with a number of posters on the walls. The setting was meant to be a ‘Wild-West’ saloon and the hand-painted posters depicted ‘Wanted’ outlaws. The outlaws, of course, were some of the Prefects and reasonable caricatures had been achieved. I was ‘Procrastinatin Pete’; I hadn’t been aware, then, of this failing! I have been trying to live up to it ever since! After the show we were given ‘our’ posters and I had mine for a long time but it is now lost. The action of the sketch was a series of interchanges with different staff mimicking individual Prefects. It was an opportunity for them to get their own back because we were always ‘taking-off’ some of them. Their observation was acute and their acting very good as they showed all the mannerisms we could recognise though may not have realised. I think Cyril Edlin mimicked Dennis Grimsley.

The Scout troop also put on ‘Gang Shows’. All I can remember of them is singing the theme tune that introduced the show,

We’re riding along on the crest of a wave and the Sun is in the sky,

All our eyes on the distant horizon look out for passers-by.

We’ll do the hailing while all the ships around us sailing.

We’re riding along on the crest of a wave and the world is ours!

I took the School Certificate exam (roughly equivalent to GCE ‘O’ level) at the end of the Vth form year, 1947 and went into the Lower VIth Science form the following September. For the Higher School Certificate (precursor of ‘A’-levels) the usual pattern was to take papers in 3 main subjects and 2 subsidiary subjects. (Note that this is long before AS-levels were thought up.) Presumably the aim was to give us as broad a base as possible and not be overloaded, as we might have been taking 4, or more, main papers. On the Science side the usual package was Physics, Pure Mathematics and Chemistry as main subjects with Applied Mathematics and Biology as subsidiary. Some took Biology as a main subject instead of Maths. For the subsidiary subjects we shared some of the lessons with those taking them as main subjects but while they did more Biology, say, we did more Maths. The budding doctors took full Biology; one I recall was Basil Shardlow.

The idea of ‘General Studies’, as at ‘A’-level, had not been introduced but each week we had at least one period when we discussed all manner of topics. We were encouraged to read newspapers and other things outside the syllabus. The Head, Mr Moodey took us for some of these and introduced us to ‘Straight and Crooked Thinking’. Here we met the fallacy “All crows are birds, all crows are black, therefore all birds are black”. He could be a bit intimidating, partly because of his position and partly because of his rather heavy, grey looking (moody?) face. After the Head’s tragic death Norman Cleave took these periods; he was not at all intimidating although a man with a definite presence.

Early in the Upper VIth year we were told about university entrance, although some boys had decided to leave a start a career, such as accountancy, on the basis of their Higher School Certificate results. UCAS didn’t exist in those days, one simply applied directly to whichever, and as many, universities as one chose. Nottingham, Manchester and Leeds were popular choices because, I expect, they were ‘northern’ universities in the NUJMB group whose School and Higher School Certificate examination papers we sat. The school had a long tradition of sending boys to Oxford and/or Cambridge and those of us considering university were asked whether we wished to try. I decided to try and, as the entrance examinations were held in the autumn, rejoined the school for the 1949-50 year while many of my contemporaries left to go to directly to university or to do their National Service first.

Some of us had visited Oxford before. Several members of staff were Oxford graduates and one, ‘Bill’ Read, had led a day trip there and shown us around. On one occasion we were shown around the Museum of the History of Science – the director, F.Sherwood Taylor had been guest speaker at one of the Speech Days. For the entrance examination we had to spend two or three days in one of the colleges. As well as the papers in our chosen subject there was a general paper for which, amongst other things, one had to translate pieces from Greek, Latin and French. My French was pretty poor and I had no chance of attempting the others as I had chosen to take Biology rather than Latin for School Certificate. After an interview I was offered a place, but told I must pass a Latin exam, since it was still a requirement for entry, whatever subject one was to read. The interviewer said, “Go away and do your National Service and learn Latin! See you in two years time”. Back at school I set about learning some Latin; Jake Hammond gave me a little help but mostly I had to work on my own. There was no chance of being ready to sit the School Certificate exam at the summer term of 1950 so, as I had not yet been called up for National Service, I returned to school the following September in the hope it would help in my attempt obtain a Latin qualification. Finally I left in November to start 2 years National Service.

I enjoyed my nine years at Burton Grammar School.

When I first went to the Grammar School in late 1946, the underground air-raid shelters were still in place as raised mounds in the area where S and T rooms and the Physics lab were subsequently built. Otherwise, the grounds were open across to M room and the house fronting the main road. Earlier in the year I had visited the school for an interview with Mr Moodey, a very disconcerting experience for a young boy as he had very penetrating eyes with dark rings under them. One was fixed with a long stare as he asked questions. I’d always been good at weighing up people, but this man was unfathomable. Still, I must have done all right as I was accepted as a student, following in the footsteps of two of my uncles, James (Jim) and John Woolley in the mid 1930s.

When I first went to the Grammar School in late 1946, the underground air-raid shelters were still in place as raised mounds in the area where S and T rooms and the Physics lab were subsequently built. Otherwise, the grounds were open across to M room and the house fronting the main road. Earlier in the year I had visited the school for an interview with Mr Moodey, a very disconcerting experience for a young boy as he had very penetrating eyes with dark rings under them. One was fixed with a long stare as he asked questions. I’d always been good at weighing up people, but this man was unfathomable. Still, I must have done all right as I was accepted as a student, following in the footsteps of two of my uncles, James (Jim) and John Woolley in the mid 1930s.

In 1948 I was lucky enough to pass the 11-plus and win a place at Burton Boys’ Grammar School, becoming a “Grammar Grub” as such achievers were called. When I left Newhall School I still lived in Wood Lane but during the summer holidays we moved to High Street, Newhall. So new house, new school coincided. My parents were faced with a large bill to finance the purchase of all the accoutrements demanded by the school. I never did acquire all that was listed on the instruction sheet.

In 1948 I was lucky enough to pass the 11-plus and win a place at Burton Boys’ Grammar School, becoming a “Grammar Grub” as such achievers were called. When I left Newhall School I still lived in Wood Lane but during the summer holidays we moved to High Street, Newhall. So new house, new school coincided. My parents were faced with a large bill to finance the purchase of all the accoutrements demanded by the school. I never did acquire all that was listed on the instruction sheet. The food was provided by the School Meals Service and was delivered in metal canisters to the caretaker’s house some distance from the School Hall. Meals cost 5d a day when I first started but had shot up to 7d by the time I left. In current money this is 10p to 15p per week. You could, if you wished, take your own cold collation. At morning break a bun and a jam doughnut were on offer at the tuck shop on the opposite side of Bond Street. This was run by the Rawlings sisters, Lily and Gertie. The cost was 3d for two buns, 1d and 2d respectively; to buy them singly was a halypenny more each. The sisters were also unofficial school nurses, tending to minor injuries.

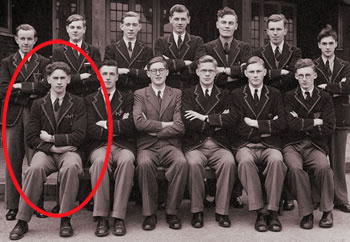

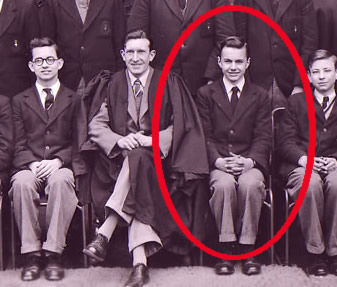

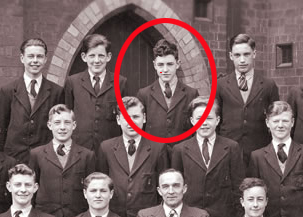

The food was provided by the School Meals Service and was delivered in metal canisters to the caretaker’s house some distance from the School Hall. Meals cost 5d a day when I first started but had shot up to 7d by the time I left. In current money this is 10p to 15p per week. You could, if you wished, take your own cold collation. At morning break a bun and a jam doughnut were on offer at the tuck shop on the opposite side of Bond Street. This was run by the Rawlings sisters, Lily and Gertie. The cost was 3d for two buns, 1d and 2d respectively; to buy them singly was a halypenny more each. The sisters were also unofficial school nurses, tending to minor injuries. I was at the school from 1945 to 1951 and in many ways the final year was the happiest of the whole time. For various reasons, mainly due to the fact that the minimum age for sitting the new GCE was 16, I repeated a year in the 5th form known as 5CII. It was there I made two very good friends, whom I’m happy to say, I still meet even now, namely Ray Gilbert (shown here with Frank on the right) and Peter Booth, whom we knew at ‘Banty’. It was also a happy year because I was familiar with the syllabus, plus a set of very fine masters, i.e. Ellick Ward for French, ‘Bomber’ Jones for History, Mr Snape, whom we referred to as the Humber Super Snape, ‘Butch’ Barrett for Religion, Norman Jones Chemistry and last, but by no means least, dear Harry Smith for Physics and Maths. Incidentally, Harry taught me for one year at Derby Tec’ for A-level Geometry and I can remember quite well when he put the alternative segment theory on the blackboard. “Come on Toon, you should know this,” was his remark. One never forgot his way of teaching us Fundamental Principles including the method for learning sines, cosines and tangents; i.e. ‘Percy Has Bought His Penny Bun’ for ‘perpendicular, hypotenuse and base’ or when we got on to what he called Ladies’ Maths, i.e. perms and combs. Lastly, when he dictated geometry homework, we would have a rectangle Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog.

I was at the school from 1945 to 1951 and in many ways the final year was the happiest of the whole time. For various reasons, mainly due to the fact that the minimum age for sitting the new GCE was 16, I repeated a year in the 5th form known as 5CII. It was there I made two very good friends, whom I’m happy to say, I still meet even now, namely Ray Gilbert (shown here with Frank on the right) and Peter Booth, whom we knew at ‘Banty’. It was also a happy year because I was familiar with the syllabus, plus a set of very fine masters, i.e. Ellick Ward for French, ‘Bomber’ Jones for History, Mr Snape, whom we referred to as the Humber Super Snape, ‘Butch’ Barrett for Religion, Norman Jones Chemistry and last, but by no means least, dear Harry Smith for Physics and Maths. Incidentally, Harry taught me for one year at Derby Tec’ for A-level Geometry and I can remember quite well when he put the alternative segment theory on the blackboard. “Come on Toon, you should know this,” was his remark. One never forgot his way of teaching us Fundamental Principles including the method for learning sines, cosines and tangents; i.e. ‘Percy Has Bought His Penny Bun’ for ‘perpendicular, hypotenuse and base’ or when we got on to what he called Ladies’ Maths, i.e. perms and combs. Lastly, when he dictated geometry homework, we would have a rectangle Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog. The school was situated in Bond Street, a narrow side street off the Lichfield Street. It was an old-fashioned building with classrooms leading off a main hall. What had been the Headmaster’s house, on the corner of Lichfield Street and Bond Street had been taken over to provide some classrooms and accommodation for the caretaker (at that time a Mr Hudson). During my time 3 sets of semi-prefabricated classroom buildings were erected in the garden between the hall and the house; two were each made up of 2 classrooms (S & T and R & Q), the third was a new physics laboratory.

The school was situated in Bond Street, a narrow side street off the Lichfield Street. It was an old-fashioned building with classrooms leading off a main hall. What had been the Headmaster’s house, on the corner of Lichfield Street and Bond Street had been taken over to provide some classrooms and accommodation for the caretaker (at that time a Mr Hudson). During my time 3 sets of semi-prefabricated classroom buildings were erected in the garden between the hall and the house; two were each made up of 2 classrooms (S & T and R & Q), the third was a new physics laboratory.