John P Bull (1927-34) – Natural History became Biology

Until the late nineteen twenties, it was Natural History taught by the greying and kindly Mr Storer who lived handily in a large house at the Bond Street end of High Street. Appropriate to his subject but not to the man was the nickname ‘Pongo’. Lessons seemed to be in the late afternoon in the draughty classroom/laboratory on the first floor beyond the Masters’ common-room. The wind rattled the dark blinds and, by the blackboard, hung a roll-down picture of the ‘Corvidae’; the group of birds that contains the crows, ravens, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs and nutcrackers. On this a large rook presided over the lesson as did the portrait of John Jervis, Admiral Lord St. Vincent at the head of the stairs outside. The textbook was an impenetrable work by Stenhouse and, like the Corvidae, it was seldom referred to in the lessons. We were encouraged to report the various wonders we had seen, or imagined we had seen, like white blackbirds and unusual nesting sites – a selection would later be published in ‘The Cygnet’.

Until the late nineteen twenties, it was Natural History taught by the greying and kindly Mr Storer who lived handily in a large house at the Bond Street end of High Street. Appropriate to his subject but not to the man was the nickname ‘Pongo’. Lessons seemed to be in the late afternoon in the draughty classroom/laboratory on the first floor beyond the Masters’ common-room. The wind rattled the dark blinds and, by the blackboard, hung a roll-down picture of the ‘Corvidae’; the group of birds that contains the crows, ravens, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs and nutcrackers. On this a large rook presided over the lesson as did the portrait of John Jervis, Admiral Lord St. Vincent at the head of the stairs outside. The textbook was an impenetrable work by Stenhouse and, like the Corvidae, it was seldom referred to in the lessons. We were encouraged to report the various wonders we had seen, or imagined we had seen, like white blackbirds and unusual nesting sites – a selection would later be published in ‘The Cygnet’.

Mr Storer had also assembled much of the collection that used to reside in the cabinets leading to the Biology lab at Bond Street.

Then suddenly Mr Storer disappeared, the subject became Biology and the teacher a young Cambridge graduate, R G Neill (pictured), fresh from research work at the Plymouth Marine Biology Station (and, I believe, free also from the ‘benefits’ of teacher training). Soon the Corvidae and the white blackbirds were replaced by the different sources of evidence for Evolution and the latest chemistry of Photosynthesis. The genetics of Drosophila were just being explained in terms of genes and chromosomes. Sturtevant, one of the American researchers came to England on a lecturing visit and somehow we got specimens of the fruit-flies and tried to repeat some of his work, feeding the tiny insects on a banana mixture in jam jars.

Then suddenly Mr Storer disappeared, the subject became Biology and the teacher a young Cambridge graduate, R G Neill (pictured), fresh from research work at the Plymouth Marine Biology Station (and, I believe, free also from the ‘benefits’ of teacher training). Soon the Corvidae and the white blackbirds were replaced by the different sources of evidence for Evolution and the latest chemistry of Photosynthesis. The genetics of Drosophila were just being explained in terms of genes and chromosomes. Sturtevant, one of the American researchers came to England on a lecturing visit and somehow we got specimens of the fruit-flies and tried to repeat some of his work, feeding the tiny insects on a banana mixture in jam jars.

Neill (‘Reggie’) had an awkward manner but his penetrating intelligence and devotion to his task made many who might come to scoff remain to learn. His lessons were soon assembled and published in his admirable ‘Aids to Biology’, a miraculous alternative to ‘Stenhouse’. His writing style was precise; he was an admirer of H L Menchen and a favourite quotation was that some claim was ‘neat, plausible and wrong’.

The ‘Biology Sixth’ particularly appreciated the clear scientific approach and his enterprising new schemes. There were weekly excursions on bicycles to Hoar Cross to take measured samples of pond life; the counts of animals were correlated with records of pH and temperature. To keep the catch we constructed a series of aquaria with an aeration tower some ten feet high for the water circulation. Another ambitious construction provided the stage which could be erected in the Hall for dramatic performances (I recall that the generous lighting we organised demanded 30 amp wiring). Mr Davies and Mr Neill collaborated in writing and producing the shows.

Some remember that ‘Reggie’ Neal’s desk in the Biology lab stood on a platform. whcih no one was allowed to step on. If they did they were told in no uncertain terms “get off my quarter deck boy.”

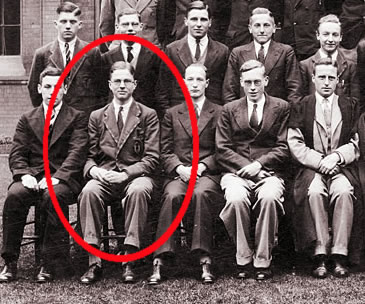

Mr Neill was also responsible for taking groups of Grammar School pupils on field trips. One such excursion was a summer cycle-camping holiday to the Lake District. This photo shows him standing with C.H. May and Frank Shotton with (left to right) James Woolley, WMN, CM and John P. Bull seated.

Mr Neill was also responsible for taking groups of Grammar School pupils on field trips. One such excursion was a summer cycle-camping holiday to the Lake District. This photo shows him standing with C.H. May and Frank Shotton with (left to right) James Woolley, WMN, CM and John P. Bull seated.

Another outstanding trip was to the Port Erin Marine Biology station in the Isle of Man. What could be a more enjoyable way to study than to row round a sunny bay and pick up samples of Sea Urchins from the clear pebbly sea floor!

Another of Neill’s literary favourites was ‘The Hunting of the Snark’ and we vied with one another to find appropriate quotations for the various adventures on our journeys – there was never any doubt as to who the ‘Bellman’ was.

Reggie Neill left the school during the war years, being replaced as Biology master during his absence by teacher from Newhall called Connie Illsley. Mr Neill returned to the school after the war.

It seemed incongruous that RGN was knowledgeable about spiritualism; we never knew whether his claim to have an aunt who levitated was just a spoof, but he turned such matters to good advantage in his historical novel ‘The Witches of Pendleton’. After marrying late in life, he retired to his beloved Lake District where he continued with success his third career as a novelist.

His first novel under the name of Robert Neill was ‘Mist over Pendle’, published in 1951. The success of this led to other novels, including ‘Moon over Scorpio’. By the time of his last book, ‘The Devil’s Door’, being published in 1979, he had sixteen books published.

Robert Neill made good contribution to the life of Burton Grammar School and to the achievements of many of its pupils. Several, such as Dr J.P. Bull C.B.E, C.H. ‘Bert’ May, whose prize giving book can be found elsewhere on the website, and Archie Grain who tragically did not survive the War; also John Woolley, Research Chemist with ICI and expert on photography and caves. His brother Jim and Noel Perks who both became teachers and Frank Shotton an Agricultural Scientist all feel endebted to Mr Neill for his influence and teaching.