I started at Burton Grammar School around 8-45am on September 7th 1950. Mick Johnson who also lived in Albert Street, and I, were the first boys from there to attend BGS. It was a street of terraced houses of Victorian origin, with two double bedrooms and one single bedroom, cold running water in the kitchen, a coal fired copper to obtain hot water which could be ladled out into the tin bath or used for doing the washing, and an outside flush toilet next to the coal house in the yard.

I started at Burton Grammar School around 8-45am on September 7th 1950. Mick Johnson who also lived in Albert Street, and I, were the first boys from there to attend BGS. It was a street of terraced houses of Victorian origin, with two double bedrooms and one single bedroom, cold running water in the kitchen, a coal fired copper to obtain hot water which could be ladled out into the tin bath or used for doing the washing, and an outside flush toilet next to the coal house in the yard.

Mick and I travelled to school on a number 5 Corporation bus which fortunately took us from Derby Street at the top of our street, to the bus stop in Lichfield Street almost outside the old Headmaster’s House of the Grammar School.

I had heard that new boys were given a rough ride on their first morning, but I cannot remember anything untoward happening to us on our arrival. Despite the mention in the letter, received by my parents, of tests to determine which class we would enter, I don’t recall any form of testing, I and 30 other boys were allocated a place in 1A and Mick went to 1B.

After a few days I made friends with Tony Yarranton, also in 1A, who lived in Victoria Street, which was an adjoining street to where I lived, so we sat together on the bus, if seats were available. Mick Johnson and I never associated with one another in school again until we were reunited in 5X in 1955. It was very much a ‘Class System’, boys very rarely mixed with members of other forms and each form had a designated area of the schoolyard which they assumed as they progressed through the school.

My parents had bought me a full sized bicycle for passing the 11+; it was a Hercules Sports, with 3 speed hub gears, cable brakes and included a saddle bag and bell. I found out after I had owned it for a day that the reflector on the rear mudguard was missing, but returning to the vendor, a shop on the corner of New Street and High Street, to have one fitted, I met with strong resistance but with promises to get one in, which came to nothing and I eventually gave up. Anyway the bike was in superb condition, despite the absence of a rear reflector, due to a weekly clean and polish whether it needed it or not, and I was rather loath to take it to school.

My parents had bought me a full sized bicycle for passing the 11+; it was a Hercules Sports, with 3 speed hub gears, cable brakes and included a saddle bag and bell. I found out after I had owned it for a day that the reflector on the rear mudguard was missing, but returning to the vendor, a shop on the corner of New Street and High Street, to have one fitted, I met with strong resistance but with promises to get one in, which came to nothing and I eventually gave up. Anyway the bike was in superb condition, despite the absence of a rear reflector, due to a weekly clean and polish whether it needed it or not, and I was rather loath to take it to school.

There were bicycle racks under cover in the area of the schoolyard near the toilets and the CCF rifle range, some wooden and others concrete. The racks in the rifle range were all wooden ones, while the shed next to it had both wooden and concrete racks, the latter being to the outside nearer the open side facing the school yard, thus bicycles were usually parked on either side of the length of the sheds with the rear wheels facing towards the centre where there was a gap of about a yard. I had seen bikes get damaged by boys being chased through the open sided shed and accidently running into a bike and buckling the front wheel. The rifle range shed was only open at one end and was therefore rather dark after about half way and is was known for items to go missing from 1st formers’ bikes parked in the dark. With this in mind I decided to use Burton Corporation Transport until I got into the 2nd form and my bike was more like the rest of those owned by older boys.

Our form master in 1A was Percy ‘Butch’ Barratt and our form-room was D Room, the entrance leading off the Hall. The windows, in groups of about four on the two outside walls, were tall but only two panes wide facing the schoolyard. It was impossible to see through to the yard as the bottom panes were frosted and the windows were set rather high up and defensively covered with wire mesh on the outside. Heating was by large (4-5 inch) hot water pipes, the boiler house being just outside D Room, near to an outer wall of the Hall. The Classroom was arranged with single desks down each side and two lines of double desks in the centre all five deep except for the left side single line which had 6 desks to accommodate the 31st pupil.

Our form master in 1A was Percy ‘Butch’ Barratt and our form-room was D Room, the entrance leading off the Hall. The windows, in groups of about four on the two outside walls, were tall but only two panes wide facing the schoolyard. It was impossible to see through to the yard as the bottom panes were frosted and the windows were set rather high up and defensively covered with wire mesh on the outside. Heating was by large (4-5 inch) hot water pipes, the boiler house being just outside D Room, near to an outer wall of the Hall. The Classroom was arranged with single desks down each side and two lines of double desks in the centre all five deep except for the left side single line which had 6 desks to accommodate the 31st pupil.

We were seated in alphabetical order from the front left (Adams) to the back right (Yarranton). Desks were the sturdy type, oak and cast iron, all in one with attached, hinged seat and lifting lockable lid. We were issued with at least one text book for most subjects, each containing a label stuck inside the front cover to be filled in by the user and the condition noted by the teacher. The information required was date, name, form, condition and initials. Exercise books were also issued, one for each subject, which were of a specific colour depending on the subject and a General Work Book. As the formroom was not used for all the lessons during the day, books not required were left in the desk and it was necessary, certainly in the 1st year, to have a lock on the desk lid. The biggest challenge to anyone using a room with locked desks was to see who could pick the lock in the quickest time!

Entry into school was around 8-50am, registration at 9-00am after the monitor had collected the register and the detention card from the office. Morning Assembly was in the Hall at 9-10am where we stood in designated places depending on the form, lower forms nearer the front. The Head would lead with a prayer followed by a hymn, the Lord’s Prayer, a reading by the Head Boy or Deputy, ending with any notices from the Head.

Lessons of 40 minutes duration commenced at 9-30am, morning break was 15 minutes at 10-50am, when, after consuming the free third of a pint of milk, most queued up at the tuck shop across the road from the schoolyard gate for an iced bun or doughnut or both from Gertie Rawlins and costing less than 2p in today’s money for both. Two more periods took us to lunch time at 12-25pm.

The Assembly Hall was also used as the Dining Room, the trestle legged tables were stacked around the wall of the Hall when not in use, these were now arranged in rows down the Hall supervised by prefects and dinner was delivered in large chrome plated vessels, which contained mashed potatoes, meat/gravy, veg., then pudding and custard, as I never stayed school dinners, having been subjected to them in 1944 when I started infants’ school, I cannot say what variations diners could expect throughout a week. I also assume that plates and cutlery were brought in with the meal and dirty plates etc. taken away as there was nowhere that any amount of washing up could be done.

Afternoon lessons started at 1-55pm and finished after three periods with no break at 3-55pm.

Subjects taken in 1A and teachers were Maths (Bill Read), Physics (The Brab), English (Jack Adams), French (Ernie), History (Butch), Geography (Ron), R.E. (Horace), Art (Mrs Biddulph), Woodwork (Taffy), P.E. (Dickie Starling), Games (Bill,Taffy, Jack, Bomber & Ron) and occasionally Music (Dickie).

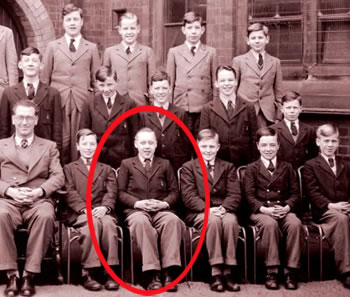

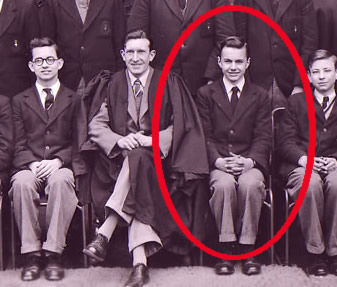

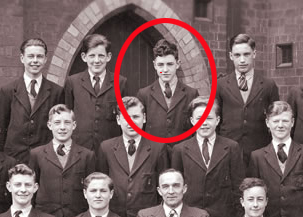

Staff members that were at the school when I started were as the 1952 staff photo with the exception of Whisky and Vic.

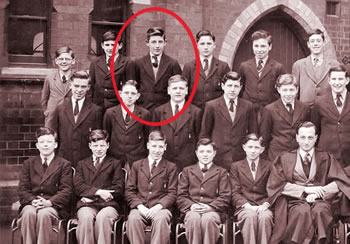

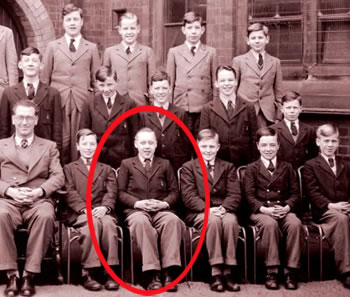

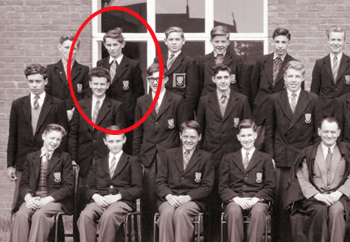

The BGS Staff in March 1952

The Staff photo was taken in the corner of the schoolyard. The small arched windows are of the junior cloakroom, the arched doorway was not generally used. The windows to the right side are those in ‘C’ room.

Back Row:

Percy ‘Butch’ Barratt, taught us History and was our form master in the first year. He got us through a difficult time settling in at a new school with very different principles to those we had been used to. I found him to be a thoughtful sort of man, coaxing answers rather that twisting your arm, he only took us for the first year, Whisky McEwan arrived the following year and undertook our Historical education. I was pleased to see Butch, who supported Nelson as Housemaster was still there at ‘the end’.

Peter ‘Tom’ Snape, taught English but I never came in contact with him. Must have left around 1954 and succeeded by Norman Roe.

Cyril Edlin, was Senior English Master and taught our form in the Senior School. Cyril was quite a character, well read on subjects of the Arts and involved with the Dramatic Society. I remember that Cyril produced rather more saliva than most while he was speaking and would remove the offending dribble from the corner of his mouth with a crooked index finger, which of course was picked up by the form wags when they did the inevitable impressions of masters. One of his favourite sayings, used by his mimics was, ‘Put it away boy!’, referring to the ruler which usually lay on the desktop with pen and pencil and was often fiddled with when answering Cyril’s question. He tragically died at his desk in 1959 aged 56.

G.A. Wain, taught French, but as with Tom Snape I never came in contact with him.

‘Whisky’ McEwan, was our History master from 2A through to 5A and I found him a very able teacher, looked forward to his lesson. He took us on an enjoyable trip Up North to visit museums which housed machinery invented during the Industrial Revolution, like Hargreaves Spinning Jenny and Crompton’s Mule, we also stopped outside a cotton mill or two. Whisky was also the BGS Scout Troop’s Leader and was our form master in 4A in ‘M’ Room.

Harry ‘Brab’ Smith, so called because of the ears, the latest large wingspan (230ft) plane being the Bristol Brabazon. Arguably the best Physics master at BGS at that time, he left under a bit of a cloud in 1953. Maths was his main subject, but he never took our form for it, but he did ‘prove’ once or twice during Physics lessons that 1=2 or 1=0 or some value that we all knew wasn’t correct! He had a wicked sense of humour and soon weighed me up, calling me Leathery and Sarky Simpson – names he addressed me by for the time he and I were together at Bond Street. Brab as Captain Smith was second in command of the Army Section of the BGS CCF, a more than able assistant to Major ‘Taffy’ Davies. He returned to BGS under better terms in 1959. He was an able teacher of whichever subject he undertook and one of the masters at BGS that left a lifelong impression on many of the students they taught.

Vic Roebuck, joined as Games master after the departure of Dickie Starling (who was really Music) in 1952. Vic’s arrival sparked a new approach to Games and Physical Education and fitness. Gone were the arms up and down, legs astride type exercises, circuit training was introduced and games lessons took on a new urgency, we even got appraisals for PE on the reports. BGS produced some notable sporting athletes in the 50’s – Mick Croft springs to mind due in no small way to Vic’s influence.

Centre Row:

Jack Adams, a tall man of impressive physique, taught English to our form until the 5th, and was our form master in 2A when we were housed in ‘Z’ Room one of the prefabs through the rifle range/bike sheds behind the lace factory. Jack was an Old Boy of the school and came to teach in 1939, was engaged in military service from 1940 to 1947, after which he returned to continue as Junior School English teacher and to be master in charge of rugby. He founded and was in charge of the Junior Dramatic Society. Jack left BGS for the Technical High School in 1956 to teach Geography, obviously another string to his bow.

Alf ‘Bomber’ Jones, started at BGS in January 1950 teaching History with some English and Games. He never taught me, but I got the impression that he was something of a disciplinarian. Alf left in 1956 to teach at Shirebrook G.S.

Ken Parkin, taught Geography but never to our form, so know little about him, must have left in 1953 when Gaffer Henton succeeded him.

Norah Mitton, was the diminutive but energetic School Secretary, efficient, helpful, discreet and fiercely loyal to the School, Staff and Boys. Norah started in 1941 when air-raid sirens disrupted the day and night, she became the ideal confidential secretary, who knew all the answers and where everything was kept, she was unflappable, even in the mayhem of the move from Bond Street to Winshill, she was the calming influence. As Winshill was some distance from where she lived and there were no direct bus routes she bought a motor scooter to enable her to get to work. She died in 1963 while on an outing with Burton Rambling Club at Sutton Park.

Mrs Biddulph, took Art, which was a subject that we (in the A form) all took for the 1st year but had to opt for Art or Woodwork in the second year, after the end of which we gave up the option in favour of Biology or Spanish in 4A. I enjoyed Art and did quite well for the two years I took it. I think Mrs. Biddulph must have left in 1953.

Mrs Edlin?/Miss Brunt?, taught Spanish, but as our form was not introduced to the language until the 4th form and then only for the modernists, I did not come into contact with her and I believe she left in late 1952/early 1953 making room, eventually, for KT Harris.

A.J. ‘Killer’ Corby, took Physics, mainly for the B & C forms I think. Wielded a pretty mean gym shoe by all accounts, thankfully never taught by him. I think he left in 1954, after which Walter Chadbourne arrived.

Ralph Hodson, second Chemistry master to Norman Jones, after 1952, started in 1950 but Norman took our form through the school so know little about Ralph. Not on the 1956 roll so I assume he left between 1953 and 1955, Reg Hardwick taking his position.

Raymond ‘Joe’ Crowther, Biology Master extraordinaire, never really strayed very far from the first floor of the ‘old’ school building, for this was where the Biology Lab and Joe’s little prep room/office were situated, together with the staff room and staff cloakroom. Those who opted for Biology in 4A would find Joe’s lessons to be interesting and sometimes eventful, especially after marked homework was handed back, anyone with less than 60% would get a whack from Joe using a thick bamboo cane/pointer (which had been wrapped with tape at the end) called Percy. One of his sayings that amused us was ‘It’s all my eye and Peggy Martin’, when someone was waffling not really knowing the correct answer. As we progressed through the school and got more confident we would rib him about Peggy Martin, making out it was some female he knew!

Despite not completing his Degree Course (thanks to Hitler) Joe decided to teach after demobilisation rather than return to University, finally joining BGS in January 1948. Joe’s work was recognised by biologists all over the country and corresponded with scientists at Oxbridge, London and Aberdeen Universities, and was invited to join the Gulbenkian Committee for the reform of the GCE ‘A’ Level syllabus in Biology. He inspired many a student to take up a career in Biology, two of whom were in my form, both becoming professors at the University of Calgary.

Looking back, Joe reminds me now of someone akin to Inspector Morse, with his love of classical music, and playing several musical instruments, together with his apparent preference for quite a lot of his own company. He died one evening in 1972 at the age of 52, after a normal day’s work at BGS, despite being in poor health for some time, he continued with his teaching until the end.

Norman Jones, took our form in the second year, on our introduction to Chemistry as opposed to Physics or Science (1st year). Norman was a Lancastrian, born in Greater Manchester, where his father was headmaster of the local Junior School. He came to BGS after graduation and war work in 1945, working under Mr. Nicholson. On Nick’s retirement in 1952, Norman was promoted to Head of the Chemistry Department.

Norman was firm but fair, as was necessary in an environment of hazardous substances, and willing to help anyone who needed it. He had a dry sense of humour, I remember we were doing an experiment as 2nd formers in the Chem Lab, Norman demonstrating something on his bench where the apparatus was set up. He was running through the apparatus so we could write up the experiment later, when someone asked the name of a specific piece of the equipment which was supporting the receiving vessel, without a change of expression Norman said it was a ‘doofer’. Not knowing any difference our diagrams of the apparatus in our Chemistry Books showed the item labelled doofer, doofah, dewfer or spelt whatever way we had perceived it. Norman never corrected it in anyone’s book and never mentioned it again.

Norman took my form through the school from the 2nd year and was responsible for my passing Chemistry ‘O’ level, making me finally understand that some work was needed to be done by myself to get a pass, – they don’t give you one for turning up, lad!

Ellick ‘Ernie’ Ward, was known to virtually every student as Ernie and I never knew that the ‘E’ stood for Ellick until around 2002, when I saw it on Tom Casey’s website.

Ernie was responsible for our French education all through the school to GCE ‘O’ level. I found him an excellent teacher, one that got work out of you with the minimum of fuss. I can’t recall him getting angry with anyone, yet he maintained a quiet discipline in the classroom.

He was interested in radio and ran the Radio Club as well as the Stamp Club, two of the several after school activities which ‘kept us off the streets’. He organised exchange visits of French students and annually took a group of BGS students to Belgium or France during one of the end of term breaks.

Front Row:

Gertrude ‘Polly’ Lownds, started in 1943 and although qualified in English, History and French, she taught Maths, her main subject, to the Junior School B and C forms.

She was involved in a rather unsavoury incident around 1953 when she was physically attacked by a student in the classroom, an act for which the student was publicly suspended; I’m not sure whether he was eventually expelled.

Polly was involved with the production of the Junior Dramatic Society plays, and in charge of National Savings collections. She was also a stalwart of the School Choir. She retired in 1960.

Joseph ‘Jake’ Hammond, the fearsome (to the younger boys) Latin Master arrived to teach ‘Classics’ in 1932. He was fervent about his subject, which was required to be passed for entrance into Oxbridge until some time in the sixties I believe, therefore it was only taught to the A stream and study began in 2A. Latin was a subject that was a novelty to begin with but after a few weeks of learning vocabulary, genders, verb conjugations and noun declensions etc., several of us with no aspirations of applying for Oxbridge, questioned the validity of the subject. Not so Jake, but to his credit he never gave up on us (strugglers), well not until 4 years’ later when I was ‘not required’ to take Latin at GCE O level. Jake was a staunch supporter of BGS, its tradition and reputation and was ready to defend ‘The School’ whenever necessary. As well as his academic background in the Classics, he was sportingly gifted, playing cricket and rugby for Burton clubs, and coaching school sides in the earlier years and Housemaster of Wellington.

There was something about Jake that made boys fearful, it was probably built out of the huge respect they felt for someone so at home with what they felt was such a difficult subject. I don’t remember him hitting anyone, he may have raised his voice once or twice, he was blunt and he told you if he disapproved, so you knew where you were with him. One of his favourite words, especially when marking your work, was ‘Chump’! Jake died in 1966 at the age of 60.

David ‘Taffy’ Davies, took us for Woodwork in the 1st year, after which I opted for Art. I didn’t lose contact with Taffy though because he was involved with games, rugby in particular and was ever present on the field in the winter afternoons refereeing during Games periods. If the weather was such that the field was unfit to play on, he would explain the rudiments of The Game to us, gathered in the Woodwork Workshop.

Taffy had a great sense of humour and a lively wit, which was appreciated by the students, who found Taff as one of the masters they could really talk to. During my time Major D.M. Davies T.D., was an able and respected CO of the Army section of the school CCF, of which I was a member, and enjoyed at least one summer camp with him and Captain Brab Smith together with about 30 other cadets, before I transferred to ‘The Brylcreem Boys’ section.

Taffy was also a major force in the Junior Dramatic Society, and also, as one would expect of a Welshman, the School Choir. He died in 1967, aged 62.

George ‘Black Hawk’ Cooper, so named as he looked like a hawk waiting to swoop on its prey, in his black gown, with his slight stoop and glasses on his hooked nose. George was at the same school, boy and man for almost 50 years, with only a break for University, a record that very few can have equalled let alone surpassed. He served as Second Master for the last eighteen of his forty three years as a master, it was a position awarded to someone with intimate and long experience of the running of the School, and it was abolished when GHC retired in favour of the now familiar Deputy Head, who did not necessarily need that qualification.

George taught us Maths in the sixth form when his administrative duties would allow, he was absolutely dedicated to the School as one would expect of someone with an association that went back so far.

H.H. ‘Horace’ Pitchford, started at BGS in 1926 and became Headmaster following the demise of Mr. Moodey, in 1950, the same year that I arrived. It was difficult to tell that Horace had not been in the position for years. He obviously loved the School and all it stood for and woe betides any boy who let the School down in any way, shape or form. According to Horace you were a Grammar School Boy whether in uniform or not, in Burton or not, in England or not and you had a tradition, reputation and standard to maintain. He always arrived at school dressed in a suit and mackintosh (mostly), wearing a trilby and always carrying a small brown suitcase. He walked to school usually as he lived on Branston Road between Trent Street and All Saints’ Church, around half a mile away.

He would occasionally deputise for an absent master, and once or twice took us for RE. On one occasion, during a part of the lesson when we were reading a passage from the Bible, Horace would suddenly ask a question completely unrelated to the subject we were studying, like ‘Who succeeded James I as monarch of this Country?’ As this was when we were in the 1st form and were a little fearful of the Head, and probably didn’t know the correct answer anyway, we were absolutely dumb. Horace drummed the desktop with his fists and retorted, ‘Come on now, you don’t know your cigarette card History!’ Another time he asked for any boy to spell ‘syzygy’, well, no-one in the class had heard the word before let alone be able to spell it, although one or two did have an unsuccessful try. Anyway Horace finally spelled the word and gave us the definition. Strangely, four years later when I was in 5A for a second year, he took us again for RE and this time there was a different set of pupils with me, Horace asked for the dictionary definition of syzygy. Every boy had a dictionary as part of their standard issue of books, so we all opened them, most in bewilderment and I think Horace was most surprised to see my hand raised after about 15 seconds, and give forth with the definition. The spelling of the word has stayed with me ever since that day in the 1st form in 1951. HHP retired in 1958.

A.C. ‘Chazzer’ Brown, came to Burton Grammar in 1920, after four years in Flanders during WWI. He taught Geography and History to the B and C forms. He was a keen tennis player and angler, a cyclist, walker, camper, beekeeper, gardener and book lover. It was because of the latter that he enjoyed the position of Librarian at the school from 1926-1959. If ever he was needed at school, the first place to look would be the library.

C.F.L. ’Bill’ Read, took us for Maths up to ‘O’ levels and was our 5A form master in Q Room, one of the prefabs in the garden of the old Head’s House. I enjoyed the subject to a certain extent, as arriving at 10+ instead of 11+, I had missed the final year at Junior School and had no knowledge of algebra and found the mechanics of it difficult to grasp, in arithmetic I could just about hold my own but geometry was my forte and had no problem with that. So I was a bit of an enigma to Bill and others and it was put down to my not really putting in the necessary effort. It took four years of verbal chastisement by one or two masters before I finally put in the effort (in most subjects) required.

I remember Bill would pick on someone in the class to factorise (a-b) 2 and stroke the back of his head as he recited each part of the answer, if he went wrong, he got a smart smack (a kep) to the head. Bill had a lighter side to his nature though, showing us card tricks one afternoon at the end of term form period just before Christmas.

Bill, who started at BGS in 1929 was a keen sportsman and Drake was his House (mine too), in his younger days he had been a swimmer, rugby and tennis player. He refereed rugby matches in Games periods and inter-house. When he was in charge of Swimming, the team was almost invincible and the Tennis six took some beating too. Bill devoted a lot of time in connection with the ATC and then, the CCF RAF section where he was Flt. Lt. Read.

Yet another master who loved his subject, his School and the people associated with it. Bill Read died suddenly, shortly after retirement in 1970.

Ron Illingworth, was our Geography master, it was a subject that I never really got to grips with so never enjoyed. Whether it was the layout of G Room in which Geography was always taught, with its tiered levels of desks rising from front to back, (it was previously the Chemistry lecture room) that made you feel there was nowhere to hide, I don’t know. Ron was always so laid back, rarely getting out of his chair behind his desk, the former defying the laws of gravity as Ron tilted further and further back. He never seemed to use text books or notes and everything came out so easily, he was certainly a master of his subject. Whenever he did find it necessary to stand in front of the class, he would almost always have at least one hand in his pocket, fiddling with whatever was in the pocket. This of course caused a stir and furtive glances by some in the class, and much discussion after the lesson.

Ron was a very good cricketer, with a perfect technique and great timing, and a hard hitter, he was very critical of batsmen that ‘didn’t get in line’. He also played rugby at County level in his younger days and his knowledge and expertise was useful to the School fifteens, he was Housemaster for Clive. Ron retired in 1972 after 36 years at BGS.

H.C. ‘Woody’ Wood, senior French Master arrived in 1945 and was there at the ‘end’. Didn’t take us in the junior school at all for French, but I remember having him for Music Appreciation once where we listened to ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’, or whatever it’s proper title is, in the Upper Sixth’s room in the old house; probably the only place in the school where there was a record player! I always think of that day when I hear the piece or see the Mickey Mouse cartoon of it.

Woody was an active member of the Alliance Francaise which promoted the French Language and culture around the world, and was honoured more than once for his work with the organisation. He was another of the masters who would go on to enjoy a very long career at the school spanning both the Bond Street and Winshill schools.

Three masters who are not on the photo are Dickie Starling, Senior Physics master D. Shorthose and The Rev P.V. Appleton, Music & RE:

D. ‘The Drip’ Shorthose, Senior Physics Master, took us after Brab left in 1953. He was a much respected member of the staff, but I had the feeling that he was looking more towards retirement than encouraging those who were finding Physics hard work. I’m not sure whether he left early or went to his birthdate as his replacement, Ezra Somekh started after the New Year in 1956.

D. ‘The Drip’ Shorthose, Senior Physics Master, took us after Brab left in 1953. He was a much respected member of the staff, but I had the feeling that he was looking more towards retirement than encouraging those who were finding Physics hard work. I’m not sure whether he left early or went to his birthdate as his replacement, Ezra Somekh started after the New Year in 1956.

P.V. ‘Pippinhead’ Appleton, became Music/RE Master in 1952 after Dickie Starling left at the end of the Winter Term in 1951. He was also Vicar of Rangemore and Dunstall and an Old Boy of the School. He possessed an extremely versatile singing voice and would sing any part to demonstrate the effect he required when training the choir for Speech Days and Carol Services. He left in 1960, to become Succentor of Lincoln and Head of the Cathedral Choir School at the end of Winter Term.

P.V. ‘Pippinhead’ Appleton, became Music/RE Master in 1952 after Dickie Starling left at the end of the Winter Term in 1951. He was also Vicar of Rangemore and Dunstall and an Old Boy of the School. He possessed an extremely versatile singing voice and would sing any part to demonstrate the effect he required when training the choir for Speech Days and Carol Services. He left in 1960, to become Succentor of Lincoln and Head of the Cathedral Choir School at the end of Winter Term.

As new boys at BGS, we found ourselves as very much the smallest and insignificant group of boys, quite a change from our standing at the Junior Schools we had just left. I cannot recall any bullying or abnormal abuse by boys in higher forms, prefects may have shouted and perhaps occasionally resorted to physical punishment, but that was usually a light ‘kep’ and anyway it came with the territory.

We were expected to respect the teachers at all times, both in and out of school, if a teacher was encountered outside the surrounds of the school and the boy was in school uniform, he was expected to doff his cap and greet the teacher in a civil way. They would be addressed as ‘sir’ or ‘miss/mrs/mr’ followed by their surname, and although every teacher had a nickname, which we soon discovered, we never dared call them it to their face.

One of the most difficult things to get accustomed to was the fact that our form room was not necessarily the room in which we were having the lessons, as in previous schools. We were given a timetable to fill in s with the lessons for each day of the week and the rooms they would be in. It was then our responsibility to ensure that we turned up at the right place at the right time and with the appropriate books for the lesson we were about to have. We were able to return to form rooms at morning break and again at dinner time, but we could be carting books around in our satchel for up to 3 periods in the afternoon as there was no break.

Several boys looked forward to Games, and playing on the School’s own playing field which was situated together with a pavilion, behind Peel Croft on Lichfield Street. It was a totally new experience having to play rugby football instead of soccer, which most of us had played at junior school, several boys representing their school in Ellis Shield matches. Many of us were interested in the newly formed local team Burton Albion, who played in the Birmingham League on the Lloyds’ Foundry football field which was down Wellington Street extension (then). A gang of BGS 1st and 2nd years would congregate behind the goal at the Railway End on most Saturdays and shout our advice to the players and the referee sometimes. We would watch most home games of the Reserves on the Saturdays that the first team played away as few could afford the coach or train fare to travel and hardly anyone had access to a car ride, although we used to bike it to see the matches against Gresley Rovers. Our interest in soccer was greater than that for rugby, but some did eventually manage a foot in both camps, although one in particular never wavered. Toff Neal played in goal for Grange Street Junior School and has been a staunch supporter of Burton Albion since 1950, he never let rugby interfere with his true love. He also played over 500 games for Winshill FC from 1960 travelling from Birmingham for each match.

During the first three or four years at BGS, the FA diehards (mainly Toff) would organise an inter form or inter year football match during a term or half term break. A proper field would be used – can’t remember how we got it – and I presume a proper ref. I remember playing on a field off the left hand side of the Trent Bridge, (facing Winshill) on a couple of occasions and well remember getting my nose broken in a collision with, I think, Bob Warrington, in a match on Shobnall Fields, which necessitated my spending the rest of the morning and most of the afternoon in Burton Hospital A&E.

We were told by Horace that rugby was played at BGS because it was a game that relied much more on teamwork than soccer and would instil in the boys that it was necessary to work together to achieve the best results. It didn’t stop a group of us changing quickly and getting out on the field to play ‘popping in’ with the oval ball and the H posts during that first term.

The rules of the game were not that difficult to learn apart perhaps for offside which seemed to be about as contentious as the same rule in soccer, we were also given instruction by Taffy Davies in the woodwork workshop on afternoons when it was too wet to play.

I remember that later on, when we played ‘proper’ 15-a side games, more pitches were required and one match had to be bussed to Shobnall Fields up by Marston’s Brewery. This meant that after changing, the two teams playing ‘away’ would walk back down the drive to board the awaiting Corporation double-decker bus for the journey. The most direct route, via Moor Street couldn’t be taken because of the low headroom of Moor Street railway bridge, so the journey took that little bit longer via Station Street and Wellington Street and of course back again, making for a shorter games period.

Cross-country was introduced to us after Christmas and was something completely different, I suppose it was character building; I found it exhausting. As juniors the course was not too demanding to those who were fit – from the pavilion on the BGS playing field behind Peel Croft, we went across Lichfield Street, down to Bond End, along the Ferry Bridge, down onto the Ox-Hay, up to the Cherry Orchard gate then back across the Ox-Hay via the path, under the Ferry Bridge, across to the pill box by the Trent, round that then down past the pumping station to the pill box near the school end of the Ferry Bridge and then back along the same course to the Silverway, up onto the bridge and back to the pavilion. Sometimes there would be someone at the end of the bridge to ensure everyone had done the proper course and give them their finishing position as they crossed the finishing line. Other times the master might delegate a prefect to ensure all went round the Bond End pill box, then he would clear off back to school or home. The thing was with cross-country that once finished and showered(?) and changed we could go home.

The Summer Term was for cricket and athletics. Many of us had played cricket either on the ‘Recs’ or in the streets (very few vehicles about in those days), but hardly any had done serious athletics, especially field events. There were three or four cricket games being played at the same time so it was sometimes difficult to know which fielders belonged to which game, but didn’t reduce the enjoyment. I remember on one occasion, no-one in our side had kept wicket so I was volunteered. I decided to stop most of the balls that weren’t hit by the batsman with my pads, this worked very well until the games period was over and we got changed and went to get our bikes to go home. I had been struck so many times on and around the knees that fluid had built up around the joint such that I couldn’t bend my knees to ride my bike. I had to leave it at school and take the bus home and have two days off sick. It didn’t deter me from keeping wicket, as I played for Drake junior and senior league teams as wicket keeper and for my village and works sides after leaving school, until I found I was a useful seam bowler.

Athletics wasn’t taken too seriously to begin with as the potential of the new boys was not really known. It was left until after Standards and Sports Day before the budding athletic performers were selected.

‘Standards’ was the pre-competition before Sports Day. Each discipline was given a time or distance for each age group (Class) which was set as the target, this, if achieved or bettered, gained a point for the competitor’s House. In this way a House which could encourage the most members to get the Standards could carry a large number of points forward to Sports Day, perform only reasonably well, and the win the shield, as it was the House with the highest total of points at the end of the day that triumphed.

The School produced some outstanding local athletes during my time there, probably the most outstanding being Michael (Mick) Croft who held the school records for 100yards, 220yards, long jump and the shot. What a pity he lost his life in a road accident before his full potential was realised.

Throughout the year there were occasions when School teams would play against teams comprised of Old Boys. The two main events were Rugby and Cricket matches, with, I think, a game between the Staff and the 1st XI.

Weather permitting; those in the school not involved with the matches were taken over to the games field or Peel Croft to watch. I suppose it was somewhat of a social occasion as far as the adults were concerned and there was probably some form of entertainment later on, but we boys regarded it as an afternoon off school even though the air temperature for the rugby match could be approaching zero.

On one these occasions in the summer we had taken our bikes over to the game for a speedy getaway, parking them in the driveway up to the School field, as the event had taken place on Peel Croft. Some boys had climbed over the fence on the clubhouse side of the field and had dropped down on the other side onto the bonnets of cars parked in the driveway, obviously damaging them. We climbed over on the opposite side to get to our bikes in the sports field driveway and rode away home. The next day there was hell to pay; Horace wanted all the boys who climbed over the fence to see him, so we went, knowing by now what it was all about and that we were in the clear, but no, we had committed the sin of climbing over the fence and although we had damaged nothing we got a Saturday morning DT for our misdemeanour.

Inter-House rivalry was quite strong with competitions in Cricket, Rugby, Cross Country, Swimming and Athletics. Cricket matches were usually played on a Saturday morning, starting quite early, when there was still a bit of moisture in the wicket, I remember a match against Clive when we (Drake) skittled them out for about 10 on such a wicket, and won by 10 wickets. Rugby was also played on Saturday morning, although I do remember playing a Sevens competition in school time, but Cross Country was done during school time in an afternoon. Athletics has been covered above, but I believe Swimming had a similar format to Athletics using Standards and culminating in an inter-House Gala in the evening.

During my time Drake and Wellington were the most successful Houses overall, so it was alright (cool in today’s jargon) to be in either of those, Nelson was OK and Clive, well I won’t mention Clive.

There were several after school clubs and societies that boys were expected to join, but I was keener to get home. I was frequently reminded that it would be beneficial to participate in after school activities, so I joined the Stamp Collecting Club as I had been given a stamp album for Christmas by an aunt. I think I went for about a term then I got a paper round, regarded by Horace as a Cardinal Sin, to help with the repayments on the new bike I’d got on the never-never. This meant that to get home in time for tea I needed to start my paper round by about 4-30 pm, so I couldn’t spare the time for Stamp Club.

My paper round was for a newsagent in Horninglow Street and we were expected to be at the shop when it opened at 6 am. As a new boy, my papers were numbered for the first two weeks after which I was expected to know the street and house numbers and the newspaper that I delivered. I would then count out the number of each newspaper required, from each pile and would be given the magazines, which were numbered. The evening round was only of Burton Mails so once learnt then I just picked up my pile, checked the number and was away. The shop was near Victoria Crescent and my round started on Tutbury Road and down Kitling Greaves Lane, so there was a fair way to go before I started and about a third of it uphill. As a relatively fit 12 or 13 years old, that wasn’t a bother until Thursday mornings when the main magazines of those days, Woman and Woman’s Own, together with the Radio Times – no ITV yet – were delivered. I needed to rest my bag on the crossbar as it was so heavy. We worked 6 days a week for 7/6d (thirty seven and a half pence). Sometimes if I went back to the shop after finishing the round, the boss would ask if I would go to the wholesaler (WHSmith) in Station Street and collect an order of a magazine or paper, and earn 2/- (10p).

Fortunately we moved house about a year later and it was too far to go, so I quit and later got a job delivering the papers for the shop in the area where I lived, for 10/- a week, got a cup of tea and a biscuit and didn’t start until 7 am.

In between the time of leaving one job and starting the next I joined the Junior Dramatic Society (JDS) as I had been in one or two plays at my Junior School. After getting a part in a forthcoming Polly Lownds’ production and attending a couple of readings, I got the chance to go on the 5th Form trip to London. Although I was only in 4A at that time, they were short of 5th formers needed to make the trip viable, so members of the 4th form were given the opportunity. Anyway it turned out that the trip would be at the same time as the performance of the play, so I missed the chance of sharing my acting talents with paying members of the general public.

The trip to London was five full days there and I believe we must have gone down by coach as I certainly remember us being bussed each day to and from the place where we stayed, which seemed like a small holiday camp in Chingford or Chigwell. I remember there was an outdoor swimming pool with diving boards and a games room inside. We had breakfast and an evening meal there.

There were usually organised or programmed visits for each morning and afternoon, except for one day when we went to Lords Cricket Ground to watch the play in the Gentlemen v Players match. As we were arriving at the ground I remember spotting Denis Compton walking in, so several of us trooped off the bus to get his autograph. We were chaperoned by Bill Read and Norman Jones (I think) and at lunch times we were told where and at what time to reassemble and left to our own devices to find somewhere to eat. There were about four of us from 4A who kept together most of the time, and we usually went to a Lyons’ Corner House and took advantage of the novelty of self-service. We usually finished our meal with loads of time to spare before meeting the rest, so we would find the nearest tube station and buy a ticket for 2d and catch the first train to come in, travel for about 5 minutes then get off at the next station, change platform and get a train back to where we started, give the ticket in to the collector and make our way to the rendezvous. Of course in those days, security was not like it is today and the price of tickets anywhere near as expensive!

Some of the other places we visited were the Science Museum, the National Maritime Museum, the Houses of Parliament and Windsor Castle. Strangely, when I was in 5A the following year, I don’t remember there being a similar trip.

One after school activity I did join and remained in for about four years was the CCF. All recruits joined the Army section, we did the usual things to start with like standing at attention, at ease and easy, then left and right and about turn, progressing to marching, about turning on the march, wheeling, halting and marking time. We learnt how and whom to salute and how to dismiss.

We were given .303 rifles and instructed how to perform the above tasks with the rifle and how to slope, order and present arms. We learnt how to clean a rifle as well as our brasses and told how to Blanco belt and gaiters, once we had been issued with a uniform.

After satisfactorily practising marching up and down in the school yard, together with several halts and right and left wheels not forgetting a mark time or two, we were deemed ready for our first route march which was duly undertaken the following week around the streets of Burton (in the vicinity of BGS).

Rifle shooting was done on the school premises in the bike shed in the yard near to Y and Z rooms. I only remember performing there once when I failed to hit the target with any of my five shots but did have the distinction of being the only one to shatter the drawing pin that held the target to the board!

We did have a session at the Butts which were off the left side of the Trent Bridge looking towards Ashby Road. I think we probably marched there via the Hay and had an afternoon off from lessons. We were instructed in the safety aspects of the range and learned the signals of the markers after each shot as they signalled the result back to the firing line – Bull, Inner, Magpie, Outer or Miss. Those not firing, manned the targets, letting them down after a firing round had been completed, to be inspected for hits. Once a hit had been confirmed and accredited, the hole would be patched over, the target hauled back into position then the marker would make the appropriate movement with his ‘disc on a stick’ then indicate where the target had been struck by placing the disc over the newly patched hole.

I attended, together with around thirty others, a summer camp at Kinmel Park which was near Rhyl in North Wales. We travelled by train from Burton and had a carriage to ourselves. We were met by Army transport at Rhyl station and taken to what was to be our ‘home’ for the next ten days or so. After we had been allocated our tent (yes we were under canvas) our first task was to draw a palliasse and get it stuffed with straw, there needed to be enough stuffing so the duckboards wouldn’t be felt, but not too much such that it was too hard and even more uncomfortable than it would be if correctly filled.

One or two things that stick out in my mind from that time are, the first or second night there was a violent thunderstorm, the rain beating on the tent together with the thunder and lightening woke any of us that had managed to get to sleep. As we were camped on the side of a hill, together with several other cadet forces from around the country, it wasn’t very long before the water started to run down the hill and underneath the duckboards, which luckily were about six inches off the ground. Eventually the whole hillside was a torrent and we could do little else but stand and watch the river of rainwater gushing under our feet. The next day on an exercise, running over some heathland I inadvertently ran into a boggy area which had been much refreshed by the overnight rain and sank to my waist in black oozy squelch before being pulled out by one of the Army squaddies that were positioned around the area for such eventualities.

I was excused duties that afternoon while my uniform was dried and cleaned.

The ablutions were outside and consisted of several cold water taps, a trough and a wooden shelf which ran the length of the trough which was used to put your stuff on whilst washing. The toilets were a ‘terrace’ of wooden built cubicles with canvas sheets on three sides and the infamous plank with a hole over a pit.

We were allocated a time for our meals and we needed to assemble outside the canteen/cookhouse area with our plates, mugs and cutlery ready to move in as soon as the eating area was clear. It was Hobson’s choice as far as the food was concerned, if you wanted it you were given a dollop of it and that was it. After the meal we had to wash our dirty plates and stuff in what probably started out as a tank of hot water outside the cookhouse, by the time we used it, it was usually lukewarm and covered with a film of greasy globules.

Evening times were usually spent in the NAAFI, where we could get a drink of something fizzy, a bite to eat and have a smoke, there may have even been a jukebox. There were some regular army members in there and they took pity on our smallest cadet, Sutton, who wasn’t much over 4 feet tall, buying him Mars Bars and giving him cigarettes.

At the weekend, on the Sunday after morning Church Parade, we were allowed the rest of the day off, but had to be back in camp by a certain time. Army transport was available to take us into Rhyl and would pick us up in time to get us back to camp before the deadline. Anyone missing the pickup was responsible for getting back by the deadline or else! Luckily no-one from our group was late back.

We were allowed to wear civvies and obviously had to fend for ourselves as regards meals. Most of us spent our time in the Funfair and on the beach, the tide went out a long way I recall, then finally a walk along the prom eating fish and chips from a newspaper, before reassembling to catch the MT. It had been an enjoyable break, and we were thankful that we had been blessed with the best day of the week so far as weather was concerned.

Each of the two weeks were packed with marches, exercises and demonstrations, one of the latter being tank warfare with in particular the use of flamethrowers which was quite exciting. In the second week we took part in a night exercise where we were the defensive force attempting to repel invading paratroopers. We needed to get our faces and hands blacked up and remove cap badges and belts. I think most of us enjoyed that and the being up all night more than the actual exercise, which, as far as I can recall, meant us secreting ourselves in some wooded area, waiting for about an hour then either capturing the invader or being ‘shot’ by him.

At the start of the second week I caught a cold and on the Wednesday night after a bout of coughing and sneezing, my nose started bleeding. Nosebleeds were a common occurrence with me until I was around eighteen, so I was quite used to it, but as I did not like swallowing the blood, I would let my nose drip until it eventually stopped. Well this particular night, I poked my head out of the tent flap and let the old conk drip. The Regular Army sentry came round and saw me and asked if I was OK and as I told him that I was, he continued his patrol. The next time he came round I was still there and he was a bit concerned and reported in to his superior, which resulted in me being taken in to the Camp Hospital on a stretcher. After being examined by the MO, I was kept in overnight, under observation. The best thing about it was that I got to sleep on a proper bed with a regular (for those days) mattress and sheets and blankets. In the morning I got a full English with toast and marmalade afterwards and was released back to my unit at about 11 am feeling much better. For about an hour after I had told them about it I was the envy of the lads in my section.

We returned home the day after, and the experience had, for me, been something I would not forget.

Later on in the next school year, I, with several other cadets, took Cert. A part 1. I had decided that when I passed I would exercise my option to join the RAF Section, which was under the command of Flt. Lt. Frank ‘Bill’ Read, as at that time, National Service was in operation, and I thought that my experience in the RAF Section would enable me to join ‘The Brylcreem Boys’ if I got called up, as that would be a cushier number. (As it happened National Service was abolished before I reached the call up age of 18).

Later on in the next school year, I, with several other cadets, took Cert. A part 1. I had decided that when I passed I would exercise my option to join the RAF Section, which was under the command of Flt. Lt. Frank ‘Bill’ Read, as at that time, National Service was in operation, and I thought that my experience in the RAF Section would enable me to join ‘The Brylcreem Boys’ if I got called up, as that would be a cushier number. (As it happened National Service was abolished before I reached the call up age of 18).

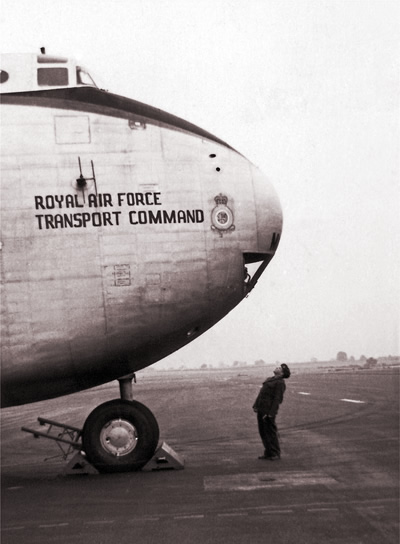

Strangely I can’t remember very much of what we did in the RAF Section, other than parading in the school yard for roll call and the one Camp that I attended. That camp was at RAF Andover in Hants and it was different from Kinmel Park in almost every respect.

We slept in a hut with beds and mattresses, the floor was covered with heavy duty lino which had to be buffed every day, for which we had a rota. There was a hut inspection every day by someone in authority and our blankets had to be folded in a particular way and arranged with the rest of the bedding neatly on top of the mattress together with mug and cutlery. Anyone who hadn’t done it correctly had to start over until it satisfied the inspecting officer. One thing that was similar to the army camp was the washing facilities, there was still only a cold water tap, trough and shelf, but we were partially covered this time. We dined in a brick built Mess-hall with the regular RAF personnel and had choice of cornflakes or porridge, followed by fried breakfast (which always featured baked beans) and bread and marmalade, the mid-day and evening meals were equally palatable.

Most of the evenings as I recall were spent playing cricket or some other ball games on the grassy bit outside the billet, before calling in at the NAAFI for something refreshing. Occasionally we would wander up to the airstrip to see what planes were taking off or landing. During the weekend the word went round that it would be worthwhile being up at the strip at a certain time on Sunday. We duly attended and were given an exhibition of some breathtaking stunt flying, by, I think, the MO nicknamed ‘Mad Mitch’, which ended with a flat out fly-by at an altitude of only a few feet. This manoeuvre, it was rumoured, could only be performed when the Station Commander was not on site.

I can only remember a couple of things that we did whilst at RAF Andover, one was an Orienteering exercise, although I doubt it was called that then. We were split into teams of three, I suppose there must have been seven or eight teams, and each team was given a sealed packet, which, we discovered later, contained a compass and an ordnance survey map of the local area. We were dressed in singlet and shorts and running shoes (plimsolls), loaded into a covered RAF transport lorry which was well sealed so we couldn’t see where we were going, and driven several miles out of the camp. While we were travelling the RAF servicemen who were organising the exercise explained the rules. After a while the lorry would be stopped, the time taken and the first team let off with the instruction to find their way back to the gatehouse using any method desired, but recommended utilising the contents of the packet. This would be repeated until all the teams had been dispersed. Under no circumstances was anyone allowed to cross the airfield to get to the gatehouse, nor trespass on private property, and there would be a monetary prize to those that got back quickest.

Our group consisted of Jonathan Underhill, John Hollins and I. We were first off the lorry and soon into our task, thanks mainly to Johnty Underhill, who obviously had used compass and map before, as it was not long before we identified an object that was shown on the map and got ourselves oriented and were making tracks in the direction of the Camp. The expertise and determination paid off because after all the times had been worked out, we were declared the winners and received the princely sum of 2/6d (12.5p) each, which probably bought 10 cigarettes, a packet of crisps and a fizzy drink in the NAAFI that night!

The other thing I remember was a trip to Boscombe Down, an MoD aircraft testing establishment. We were to fly there in an Avro Anson twin prop engined plane used by the RAF for Coastal and Bomber Command in WWII and later for pilot and bomber crew training and light transport roles. For most of us this was going to be our first flight, and though we were looking forward excitedly to the experience, we were secretly wondering if we would disgrace ourselves by being sick, and if they had the infamous brown paper bag in the RAF. As the plane was used for training, the seating wasn’t quite economy class, but we didn’t care, once we’d been shown how to fasten the seat belt and told where the brown paper bag was (phew!) everything was fine and all we were waiting for was to get into the air.

The relatively short journey, flying at around 150 mph was over all too soon and most of our stomachs were well behaved. We were much more interested in what we could see through the fuselage windows to think about being sick. Once out of the Anson we were escorted (bearing in mind there was some hush-hush stuff on site) around some of the aeroplanes on the ground, in particular the Supermarine Swift, a jet fighter which was the forerunner to the Hawker Hunter and held the world speed record of 737.7 mph for a few hours, before it was beaten by an American fighter plane in 1953. We were allowed to sit in the cockpit of the Swift and have a play with the controls. There were fewer dials and displays than there are now, as automatic computer control etc. were yet to come. One thing that did interest us was the ejector seat control button as well as the fire buttons for the armament, 2 x 30mm cannon and provision for rockets and bombs. After the tour we repaired to the Mess for refreshments before returning to RAF Andover.

Also while in the 5th form we went on a trip to the Theatre at Stratford-on-Avon to see Othello (I think), we travelled by coach and I remember that in the theatre we sat high up in the gods so it was not that easy to hear everything and the actors looked quite small. I don’t know whether some of the party managed to get to the bar during an intermission but during part of the performance some students had to be rebuked by one of the supervising members of staff for making too much noise.

As I have mentioned earlier, the lunch break lasted for around one and a half hours, so those who stayed at school for lunch, especially sandwiches, had quite a time to kill before afternoon lessons. While we were in 5A some of us set up a lunchtime league playing shove ha’penny and table tennis, In our formroom, Q room, one of the prefabs in the old garden, there was more than enough space for the average size class of around 30 pupils, which meant that there was quite a large open area between the blackboard, which was on the wall at the front, and the first row of desks. There were also a couple of tables pushed against the wall at the far side. These were pulled out for use as shove ha’penny ‘pitches’ or placed side on to Bill Read’s desk, which was turned through 90 degrees, to make a table-tennis table, with text books, set like ridge tents, across the central table as the net. There would be matches arranged between those in the league at specific times suitable to the competitors, as it wasn’t confined only to those staying at school over lunchtime, although I usually took sandwiches or rushed back on days that I was involved in a match.

I don’t recollect us getting stopped playing the lunchtime games, so it must have petered out after the champions in the particular ‘disciplines’ had been duly recognised.

After only passing four ‘O’ level subjects in the GCE, Horace thought I should go into the sixth form and take two science subjects later, but I thought I would prefer to spend a year in 5X to get the required subjects and perhaps some others, so this is what occurred. The form was comprised of about ten pupils from each of 5A and 5B plus around five from 5C, there may have been the odd one from the previous year’s 5X.

There was a mixed bag of subjects taken, those from the A stream would usually be taking less of the ‘standard’ subjects and making up with the ‘non standard’ ones like Art and English Literature combined with study periods. Those from the B stream would be taking more ‘standards’ and C stream even more. I was taking eight subjects which included PE/Games and RE, compared with the ten I took in 5A.

I enjoyed the year in 5X probably more than any other year, as there was not really that much pressure and with the study periods, much of the homework could be completed at school. As I was heavily into sport at that time, playing school sports and local badminton at junior and senior levels, together with watching Burton Albion at every opportunity, not to mention the fairer sex beginning to make an impression, the less time needed to stay in doing homework the better! We were treated more like sixth formers in as much as we could use the garden gate to access our formroom (S room – complete with coke burning cast iron stove which stood at the back of the classroom), and park our bikes in the garden, and weren’t hounded by prefects at break times, meaning we didn’t need to use the school yard at all.

Jack Adams was our form master in what was to be his final year at BGS before moving to the Technical High School to teach Geography. Strangely, I hadn’t remembered that he had left until I read it in my one surviving Cygnet when looking through stuff for Tom Casey’s website around 2001. He was my form master in my second and penultimate years, in my House (Drake) and was at school with my mother!

One notable arrival during my year in 5X was Ezra Somekh, he started in the New Year of 1956. I had struggled previously with Physics under Drip Shorthose having just failed in 5A and not doing much better the second time around. Ezra brought a new vigour to the subject and in the few months from his arrival to the time of the exam, certainly whipped me into shape, enabling me to pass where, but for him, it would have been a certain failure.

My year in LVISc is very much a blur, I presume we studied mainly Maths, Physics and Chemistry with PE/Games and things like Music Appreciation with Hubert Wood, German with Sap Greenwood, although I was excluded from his lessons after a few weeks, and the Sixth Form Society thrown in.

I can remember Maths with George Cooper, when he was able to turn up, as he was increasingly standing in for Horace as Head, because The Beak was much involved with the now imminent move to Winshill. Most of the lessons were in T room, which like its mirror image S room had the coke burning cast iron stove. When it was obvious George was either going to be late or not come at all, we would have a game of cricket with the coke shovel as bat and pieces of coke as ball. The gangway was covered with fragmented pieces of coke and if George did turn up he would crunch down the gangway with every step, but never did say a word. Another thing we did, like scores of other classes before us, was to open up the bottom air vent on the stove and get it so hot that the body of the stove glowed. George would come in and shut the vent and open a window and carry on with the lesson.

Ezra was Physics at BGS from the time he arrived until he left. I would think that perhaps he and Joey Crowther had a similar dedication to their subject and many scientists who are Old Boys of BGS from the mid 50’s to late 60’s owe much to Ezra Somekh for the way that he taught his subject.

Chemistry was with Dennis Grimsley who had just returned back to the school after University, Teacher Training and National Service. I remember that, as someone not much older than us, especially as some were seventeen and eighteen years old, Dennis was easier to talk to and it was a much lighter atmosphere than with the longer serving masters. We called Dennis Chief or Chiefy, rather than sir, and he accepted that alright, whether others had another nickname for him I don’t know. Being in the Sixth, we did seem more isolated as regards the rest of the school than before, we only saw other pupils in school at Assembly or Games, not even integrating with other sixth form students in school except for the Sixth Form Society, so the communication chain that existed throughout the lower school, was not quite so well maintained later on.

During that year in LVISc, I had made friends with someone who came up from 5A as well as another from 5X and we kept in our own little clique most of the time, we all three decided that we were going to leave at the end of the year. As the end of the Summer Term and the final days of BGS at Bond Street approached, normality began to disappear as plans were executed to make the move as easy and as quick as possible, some students in the senior school with bicycles were utilised in moving books and stationery up to Winshill. I together with one of my friends were so employed, no school for about a week while the weather was fine, a leisurely ride up to Mill Hill Lane three or four times a day and home about an hour earlier than usual.

I don’t recall being at the final assembly and singing ‘Lord Dismiss Us’ for the last time at Bond Street and I’m sure there must have been something special on that last day that I would have remembered, if there was then I wasn’t there. What I do remember is three departing BGS sixth formers throwing their caps (which we still had to wear as part of the uniform) into the Trent down by the Ice Factory at Bond End and going home ‘improperly dressed’.

Looking back, there are many things throughout my time at BGS that I wished I had done differently, and looking at the situation now I think that the decimation of the Grammar Schools and the move away from that method of education was the biggest educational disaster this country has made.

When I first went to the Grammar School in late 1946, the underground air-raid shelters were still in place as raised mounds in the area where S and T rooms and the Physics lab were subsequently built. Otherwise, the grounds were open across to M room and the house fronting the main road. Earlier in the year I had visited the school for an interview with Mr Moodey, a very disconcerting experience for a young boy as he had very penetrating eyes with dark rings under them. One was fixed with a long stare as he asked questions. I’d always been good at weighing up people, but this man was unfathomable. Still, I must have done all right as I was accepted as a student, following in the footsteps of two of my uncles, James (Jim) and John Woolley in the mid 1930s.

When I first went to the Grammar School in late 1946, the underground air-raid shelters were still in place as raised mounds in the area where S and T rooms and the Physics lab were subsequently built. Otherwise, the grounds were open across to M room and the house fronting the main road. Earlier in the year I had visited the school for an interview with Mr Moodey, a very disconcerting experience for a young boy as he had very penetrating eyes with dark rings under them. One was fixed with a long stare as he asked questions. I’d always been good at weighing up people, but this man was unfathomable. Still, I must have done all right as I was accepted as a student, following in the footsteps of two of my uncles, James (Jim) and John Woolley in the mid 1930s.

In 1948 I was lucky enough to pass the 11-plus and win a place at Burton Boys’ Grammar School, becoming a “Grammar Grub” as such achievers were called. When I left Newhall School I still lived in Wood Lane but during the summer holidays we moved to High Street, Newhall. So new house, new school coincided. My parents were faced with a large bill to finance the purchase of all the accoutrements demanded by the school. I never did acquire all that was listed on the instruction sheet.

In 1948 I was lucky enough to pass the 11-plus and win a place at Burton Boys’ Grammar School, becoming a “Grammar Grub” as such achievers were called. When I left Newhall School I still lived in Wood Lane but during the summer holidays we moved to High Street, Newhall. So new house, new school coincided. My parents were faced with a large bill to finance the purchase of all the accoutrements demanded by the school. I never did acquire all that was listed on the instruction sheet. The food was provided by the School Meals Service and was delivered in metal canisters to the caretaker’s house some distance from the School Hall. Meals cost 5d a day when I first started but had shot up to 7d by the time I left. In current money this is 10p to 15p per week. You could, if you wished, take your own cold collation. At morning break a bun and a jam doughnut were on offer at the tuck shop on the opposite side of Bond Street. This was run by the Rawlings sisters, Lily and Gertie. The cost was 3d for two buns, 1d and 2d respectively; to buy them singly was a halypenny more each. The sisters were also unofficial school nurses, tending to minor injuries.

The food was provided by the School Meals Service and was delivered in metal canisters to the caretaker’s house some distance from the School Hall. Meals cost 5d a day when I first started but had shot up to 7d by the time I left. In current money this is 10p to 15p per week. You could, if you wished, take your own cold collation. At morning break a bun and a jam doughnut were on offer at the tuck shop on the opposite side of Bond Street. This was run by the Rawlings sisters, Lily and Gertie. The cost was 3d for two buns, 1d and 2d respectively; to buy them singly was a halypenny more each. The sisters were also unofficial school nurses, tending to minor injuries. Life is punctuated by defining moments, how many defining moments we are allotted in life I have no idea, but do we recognise them when we experience them? Well, looking back on my life I can trace several, but at the time, they came and went without even registering a flicker on the Richter scale of defining moments. Apart from my birth being the first, the next must have been the year 1945, when as a 7 year old, the ending of the second world war was signalled by having a victory party held in the street where I lived, races were held, and during the 60 yard sprint I stumbled at a critical moment, it robbed me of victory my Uncle always told me. I only mention this, because 6 years of grinding war had passed me by almost unnoticed.

Life is punctuated by defining moments, how many defining moments we are allotted in life I have no idea, but do we recognise them when we experience them? Well, looking back on my life I can trace several, but at the time, they came and went without even registering a flicker on the Richter scale of defining moments. Apart from my birth being the first, the next must have been the year 1945, when as a 7 year old, the ending of the second world war was signalled by having a victory party held in the street where I lived, races were held, and during the 60 yard sprint I stumbled at a critical moment, it robbed me of victory my Uncle always told me. I only mention this, because 6 years of grinding war had passed me by almost unnoticed. I started at Burton Grammar School around 8-45am on September 7th 1950. Mick Johnson who also lived in Albert Street, and I, were the first boys from there to attend BGS. It was a street of terraced houses of Victorian origin, with two double bedrooms and one single bedroom, cold running water in the kitchen, a coal fired copper to obtain hot water which could be ladled out into the tin bath or used for doing the washing, and an outside flush toilet next to the coal house in the yard.

I started at Burton Grammar School around 8-45am on September 7th 1950. Mick Johnson who also lived in Albert Street, and I, were the first boys from there to attend BGS. It was a street of terraced houses of Victorian origin, with two double bedrooms and one single bedroom, cold running water in the kitchen, a coal fired copper to obtain hot water which could be ladled out into the tin bath or used for doing the washing, and an outside flush toilet next to the coal house in the yard. My parents had bought me a full sized bicycle for passing the 11+; it was a Hercules Sports, with 3 speed hub gears, cable brakes and included a saddle bag and bell. I found out after I had owned it for a day that the reflector on the rear mudguard was missing, but returning to the vendor, a shop on the corner of New Street and High Street, to have one fitted, I met with strong resistance but with promises to get one in, which came to nothing and I eventually gave up. Anyway the bike was in superb condition, despite the absence of a rear reflector, due to a weekly clean and polish whether it needed it or not, and I was rather loath to take it to school.

My parents had bought me a full sized bicycle for passing the 11+; it was a Hercules Sports, with 3 speed hub gears, cable brakes and included a saddle bag and bell. I found out after I had owned it for a day that the reflector on the rear mudguard was missing, but returning to the vendor, a shop on the corner of New Street and High Street, to have one fitted, I met with strong resistance but with promises to get one in, which came to nothing and I eventually gave up. Anyway the bike was in superb condition, despite the absence of a rear reflector, due to a weekly clean and polish whether it needed it or not, and I was rather loath to take it to school. Our form master in 1A was Percy ‘Butch’ Barratt and our form-room was D Room, the entrance leading off the Hall. The windows, in groups of about four on the two outside walls, were tall but only two panes wide facing the schoolyard. It was impossible to see through to the yard as the bottom panes were frosted and the windows were set rather high up and defensively covered with wire mesh on the outside. Heating was by large (4-5 inch) hot water pipes, the boiler house being just outside D Room, near to an outer wall of the Hall. The Classroom was arranged with single desks down each side and two lines of double desks in the centre all five deep except for the left side single line which had 6 desks to accommodate the 31st pupil.

Our form master in 1A was Percy ‘Butch’ Barratt and our form-room was D Room, the entrance leading off the Hall. The windows, in groups of about four on the two outside walls, were tall but only two panes wide facing the schoolyard. It was impossible to see through to the yard as the bottom panes were frosted and the windows were set rather high up and defensively covered with wire mesh on the outside. Heating was by large (4-5 inch) hot water pipes, the boiler house being just outside D Room, near to an outer wall of the Hall. The Classroom was arranged with single desks down each side and two lines of double desks in the centre all five deep except for the left side single line which had 6 desks to accommodate the 31st pupil.

D. ‘The Drip’ Shorthose, Senior Physics Master, took us after Brab left in 1953. He was a much respected member of the staff, but I had the feeling that he was looking more towards retirement than encouraging those who were finding Physics hard work. I’m not sure whether he left early or went to his birthdate as his replacement, Ezra Somekh started after the New Year in 1956.

D. ‘The Drip’ Shorthose, Senior Physics Master, took us after Brab left in 1953. He was a much respected member of the staff, but I had the feeling that he was looking more towards retirement than encouraging those who were finding Physics hard work. I’m not sure whether he left early or went to his birthdate as his replacement, Ezra Somekh started after the New Year in 1956. P.V. ‘Pippinhead’ Appleton, became Music/RE Master in 1952 after Dickie Starling left at the end of the Winter Term in 1951. He was also Vicar of Rangemore and Dunstall and an Old Boy of the School. He possessed an extremely versatile singing voice and would sing any part to demonstrate the effect he required when training the choir for Speech Days and Carol Services. He left in 1960, to become Succentor of Lincoln and Head of the Cathedral Choir School at the end of Winter Term.