Robert James was educated at Newcastle (Staffordshire) High School. From here he went to the University of Durham (Grey College) where he gained a degree in French Language and Literature and Post-graduate Certificate of Education. He played cricket for the university for four years and became captain in 1970.

Robert James was educated at Newcastle (Staffordshire) High School. From here he went to the University of Durham (Grey College) where he gained a degree in French Language and Literature and Post-graduate Certificate of Education. He played cricket for the university for four years and became captain in 1970.

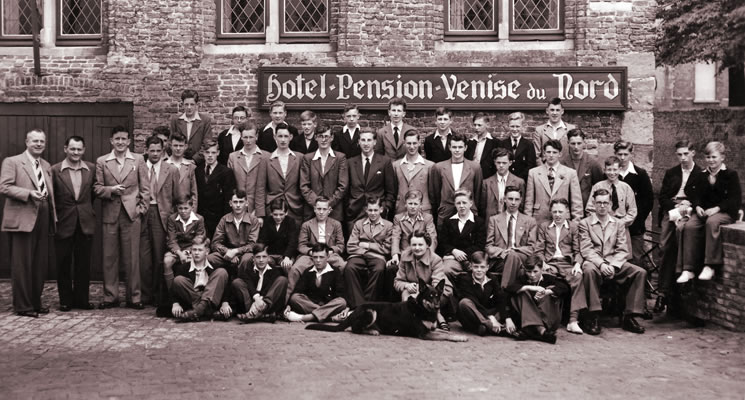

He spent one year in France at the Lycee Marceau, Chartres, as English assistant. This coincided with the student riots of May-June 1968. There was a general strike for a short time and Sixth Formers occupied the school, so effectively he had a month off work.

Bob also played cricket for Staffordshire and Derbyshire 2nd XI, played in North Staffs and South Cheshire League as both an amateur (Longton CC) and professional and was professional at the same club (Norton) where Sir Frank Worrell, Sir Garfield Sobers and Jim Laker had been professional. He also played hockey for Burton in the 70s.

His first experience of Burton Grammar School was as an opponent in a cricket match played at the Mill Hill Lane site when he was a pupil at Newcastle (Staffordshire) High School. He remembers being impressed by the view from the pitch over the Trent valley, but Burton itself seeming singularly unattractive, even to someone brought up amongst the smoke and grime of North Staffordshire.

It was therefore somewhat ironic that he was destined to spend five years as a master at the school and a further thirty-one on the same site at the Abbot Beyne School. By the time he retired, having been acting Head for a short while the previous year, he was beginning to feel like Mr Chips.

It was on a damp miserable Friday in March 1970, having made what seemed an interminable journey from Durham, that Bob had found himself being interviewed for the post of assistant French master at the school. A misty shroud enveloped the town, and the unique Burton aroma of malt, rubber and Robirch permeated everything. It did not make for a very welcoming atmosphere.

Having found his way from the station to the ‘Swan’ as a reference, he finally located the school. In fact, he arrived early for the interview, and was asked to wait in the corridor outside the office. Deputy Headmaster, Geoff Henton appeared but what he expected to be a preliminary interview turned into a pleasant chat about sport, especially rugby, as the school was agog at the prospect of the match the following day at Peel Croft – the Rugby County Championship final. It is a competition which no longer exists in these days of professional rugby, but it was in those days a major event in the sport’s calendar. Against all the odds Staffordshire, coached by one Vic Roebuck, had reached the final, a final which they were to win.

He was then shown around the French department and interviewed by Bill Gillion. To his surprise, he was offered the job. To Mr Gillion’s surprise, Bob asked for time to think about it. It was clear that here was a good department in a good school, but the thought of living in Burton on Trent was not appealing. The smell of Marmite was still in his nostrils.

Given the good prospects for a young French master, taking into account the age profile of the department, Bob’s motives for accepting the post were rather less career-orientated. He was captain of the cricket team at Durham University and a full fixture list beckoned for the summer. He didn’t want to waste time travelling around the country for interviews when he could be playing cricket!

Having accepted the post, he started in September in this prestigious school which had just celebrated its 450th anniversary. The French department was well-managed by Hugh Wood, who managed to combine old-fashioned academic rigour with new-fangled methods such as a language laboratory and an audio-visual course in the first year. He was superbly organised and the syllabus set out exactly what was to be done. Hugh was always supportive and helpful. The other members of the department were Ellick Ward and Betty Radford, who like Hugh were approaching the end of their careers. Ellick was always jovial, often making a gift of his bottles of home-made wine to his colleagues.

Having accepted the post, he started in September in this prestigious school which had just celebrated its 450th anniversary. The French department was well-managed by Hugh Wood, who managed to combine old-fashioned academic rigour with new-fangled methods such as a language laboratory and an audio-visual course in the first year. He was superbly organised and the syllabus set out exactly what was to be done. Hugh was always supportive and helpful. The other members of the department were Ellick Ward and Betty Radford, who like Hugh were approaching the end of their careers. Ellick was always jovial, often making a gift of his bottles of home-made wine to his colleagues.

Mr James also had to teach some Latin, a prospect which he did not relish, as he had studied the subject at university only as a subsidiary, and had not touched a Latin book for three years. Fortunately, John Long had only allocated him a small set of Lower Sixth pupils who had failed ‘O’ level because they had missed out the third year in order to take GCE early. They were therefore extremely bright and motivated because they needed the qualification for Oxbridge matriculation. The lessons took quite a while to prepare; he remembers spending ages sorting out the first lesson – a double – and running out of material half-way through. The lads however, sailed through the November re-sits and later went on to Oxbridge.

His first French lesson was a total disaster. It was with a first year group in the French room using the audio-visual course. After a couple of minutes the drive-band on the tape-recorder, a reel-to-reel machine which was at the cutting edge of technology at the time, broke. As one spool spun totally out of control, the desk was soon covered with yards of tape. He carried on as best he could without the machine until the bulb in the projector blew. Fortunately the lessons were only forty minutes long in those days and he somehow survived but hasn’t trusted technology since.

Living in Burton was something of the culture shock that he had feared. He rented a small bed-sit in an old house on Ashby Road owned by the Renwick family which is now an old people’s home. After four years in Durham and one in Chartres, woken each day by the sound of bells and looking out on to two of the most magnificent cathedrals in Europe, it was loud drone of beer lorries struggling up Ashby Road and the view of the water tower which now greeted him each morning.

Still, Burton had its compensations in the form of the excellent school. He was able to settle into the swing of things and was soon enjoying the work.

The staff was the usual mix of the experienced ‘doyens’ and the younger masters who definitely knew their place in the hierarchy. Amongst the former were, as well as Hugh Wood, Norman Jones, Harry Smith and Ron Illingworth. The latter was a luminary. During Robert’s first week in the school, a fearful first-former, waiting outside the Geography room, asked “Sir, is it true that Mr Illingworth throws boys out of the window?” Brave was the boy who would dare to put a foot wrong in one of Ronnie’s lessons. A shared interest in cricket meant that Bob and Ron got on well.

Harry Smith, of course, was already a legend. His teaching was inspirational and a steady stream of Sixth-formers made their way to the best universities in the country to read Maths. He also made his colleagues laugh with his deep fund of anecdotes.

All these men had great presence and were awe-inspiring to newcomers, but once Bob got to know them, they were the epitome of kindness and good humour. What struck him was the fact that many of the staff had great talents outside of their subject specialisms, whether it was in the arts or sport. Experts in their subjects they certainly were, but they were also well-rounded and cultured men.

Many of the younger staff were also gifted sportsmen and would willingly take on a team, which, in the case of rugby, meant three practices a week and a match every Saturday from the end of September to the beginning of March. The present generation of teachers, sadly, are too busy with one initiative after another to take on such tasks, and in any case, school sport nationally suffered enormously in the 80s, never to recover, despite the government’s finally waking up to the fact that competitive sport is not necessarily the evil which many progressives think it is.

Quite apart from the dedicated PE staff (the inimitable Vic Roebuck and John French) Alan Cure, a former pupil and Cambridge graduate, was a Staffordshire prop and trained the Under 15s. John Long, who could turn his hand with equal facility to rugby, tennis or cricket, took the under 14s in the winter and a tennis or cricket team in the summer. Colin Bagshaw could be seen every Saturday morning in the rugby season refereeing a match before turning his attention to cricket in the summer.

It was no surprise then that the school produced a steady supply of rugby players for the county and even the England teams. The Osman brothers, Peter Nelson and Pete Orton represented their country in the early 70s. Mr James remembers being asked by Geoff Henton if he would help him to transport some of the Under 15 team to a county match one Saturday. Half the Staffordshire side seemed to be from school. Two names that emerge from the mists of time as well as Orton were Tony Hair and John Sharpe.

Bob’s own small contribution to sport was to help John French with senior cricket coaching and take the Under 12s rugby squad. The latter was an innovation, and normally the Loughborough student would lend a hand. The first was John Appleby who became assistant head at Paulet. They were amazed at one early training session when a young lad started popping over kicks from both sides of the pitch with either foot. His name was Russell Osman, later like his elder brother Mark, to represent England Schools at rugby. He then found fame as an England and Ipswich Town centre-half. Other members of that side included Jes Redfern and Paul Green, who both made their mark on local cricket.

As far as cricket was concerned, lads such as Bob Lathbury, Graham Parkinson, Graham Milnes and David Marshall were all accomplished players, with the latter two enjoying considerable success after they left school with Bass and Burton CC respectively.

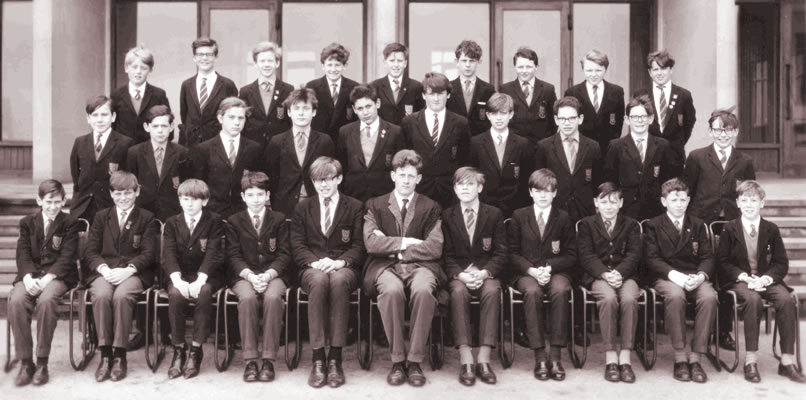

Bob was form master of one group of pupils for several years. He taught them French from 2B to ‘O’ level as well. He found them a pleasant group who worked hard (under suitably applied pressure!) and with whom you could share a joke at the same time. Names that spring to mind are Mark Turner, Paul Johnston, Dave Granville, Steve White, the Markeys, Chris Talbot and “Sam” Salt to name but a few. It was a class of over 30, much to be frowned on these days. The marking was time-consuming but the results were excellent. He had to admit to feeling very old when Chris Talbot’s son (along with Tony Di Gravio’s lad) turned up in his Citizenship group in his last year of teaching.

The final year of the Grammar School intake produced some outstanding pupils both academically and on the sports field. Graham Shaw went on to read Vetinary Science at Cambridge and played hockey in an outstanding Abbot Beyne XI which included Mick Emery, Ian Jones and Steve Morrison. (John Mills, a future Scottish international, was also in that side, but he had arrived at the school after re-organisation.)

The final year of the Grammar School intake produced some outstanding pupils both academically and on the sports field. Graham Shaw went on to read Vetinary Science at Cambridge and played hockey in an outstanding Abbot Beyne XI which included Mick Emery, Ian Jones and Steve Morrison. (John Mills, a future Scottish international, was also in that side, but he had arrived at the school after re-organisation.)

BGS ran smoothly. Bill Gillion was a typical grammar school headmaster of the time, paternalistic in his approach. Staff meetings were few and far between; the masters simply got on with the job. Bill’s deputy, Geoff Henton, was always calm and extremely helpful to young staff. Little did Bob realise that he would one day succeed him as Deputy Head. That was in 1984 after serving as Head of Department for the previous ten years.

Bob finally retired in the summer of 2006. David Mart had retired the previous year leaving Bob as the last staff link between Abbot Beyne School and Burton Grammar School.

Despite his original impression of Burton, Bob still lives locally. He is married to Yvonne with two sons. The elder son Mark did a degree at York before doing a Master’s at Loughborough before training as an accountant. Younger son Michael read Law at Cambridge. He is spending his retirement watching sport and doing some occasional sports writing (football and cricket) for both the press and websites, and coaching cricket at Rolleston CC and for Derbyshire U17s and other age-groups.

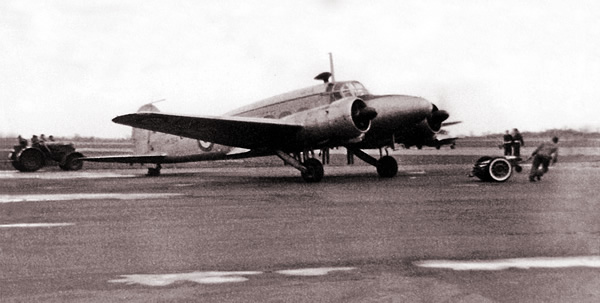

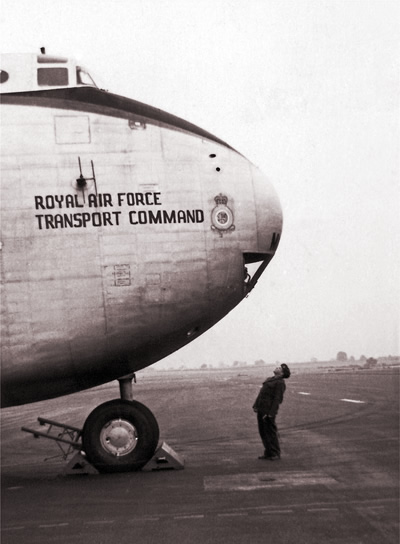

In the 1950s the RAF seemed to be very exciting. The new RAF fighter planes the Supermarine Swift and the Hawker Hunter broke several world records. The new Gloster Javelin all weather fighter had a delta wing and new Air-to-Air missiles. The iconic V-bombers were entering service. The first V-bomber was the Valiant painted in ‘anti-flash’ white. A year later there were the delta winged Avro Vulcans, then a year after that the last of the V-bomber types, the crescent winged Victors. Even RAF Transport Command had a jet transport squadron by the time I joined the Grammar School.

In the 1950s the RAF seemed to be very exciting. The new RAF fighter planes the Supermarine Swift and the Hawker Hunter broke several world records. The new Gloster Javelin all weather fighter had a delta wing and new Air-to-Air missiles. The iconic V-bombers were entering service. The first V-bomber was the Valiant painted in ‘anti-flash’ white. A year later there were the delta winged Avro Vulcans, then a year after that the last of the V-bomber types, the crescent winged Victors. Even RAF Transport Command had a jet transport squadron by the time I joined the Grammar School.

Robert James was educated at Newcastle (Staffordshire) High School. From here he went to the University of Durham (Grey College) where he gained a degree in French Language and Literature and Post-graduate Certificate of Education. He played cricket for the university for four years and became captain in 1970.

Robert James was educated at Newcastle (Staffordshire) High School. From here he went to the University of Durham (Grey College) where he gained a degree in French Language and Literature and Post-graduate Certificate of Education. He played cricket for the university for four years and became captain in 1970. Having accepted the post, he started in September in this prestigious school which had just celebrated its 450th anniversary. The French department was well-managed by Hugh Wood, who managed to combine old-fashioned academic rigour with new-fangled methods such as a language laboratory and an audio-visual course in the first year. He was superbly organised and the syllabus set out exactly what was to be done. Hugh was always supportive and helpful. The other members of the department were Ellick Ward and Betty Radford, who like Hugh were approaching the end of their careers. Ellick was always jovial, often making a gift of his bottles of home-made wine to his colleagues.

Having accepted the post, he started in September in this prestigious school which had just celebrated its 450th anniversary. The French department was well-managed by Hugh Wood, who managed to combine old-fashioned academic rigour with new-fangled methods such as a language laboratory and an audio-visual course in the first year. He was superbly organised and the syllabus set out exactly what was to be done. Hugh was always supportive and helpful. The other members of the department were Ellick Ward and Betty Radford, who like Hugh were approaching the end of their careers. Ellick was always jovial, often making a gift of his bottles of home-made wine to his colleagues. The final year of the Grammar School intake produced some outstanding pupils both academically and on the sports field. Graham Shaw went on to read Vetinary Science at Cambridge and played hockey in an outstanding Abbot Beyne XI which included Mick Emery, Ian Jones and Steve Morrison. (John Mills, a future Scottish international, was also in that side, but he had arrived at the school after re-organisation.)

The final year of the Grammar School intake produced some outstanding pupils both academically and on the sports field. Graham Shaw went on to read Vetinary Science at Cambridge and played hockey in an outstanding Abbot Beyne XI which included Mick Emery, Ian Jones and Steve Morrison. (John Mills, a future Scottish international, was also in that side, but he had arrived at the school after re-organisation.)

The Secretary of State for Education at the time however, refused to re-open the direct grant list. Given that person’s later education policies, this may seem surprising – it was none other than Margaret Thatcher. Fifteen years or so later, her government’s Education Reform Act set up Grant Maintained Schools to free schools, if they so wished, from the dead hand of local authority control. By that time, the old Direct Grant Schools had been forced by the previous administration to choose either to go totally independent or be subsumed into the local authority system.

The Secretary of State for Education at the time however, refused to re-open the direct grant list. Given that person’s later education policies, this may seem surprising – it was none other than Margaret Thatcher. Fifteen years or so later, her government’s Education Reform Act set up Grant Maintained Schools to free schools, if they so wished, from the dead hand of local authority control. By that time, the old Direct Grant Schools had been forced by the previous administration to choose either to go totally independent or be subsumed into the local authority system. Everything happened at break-neck speed. The new school had to be up and running within months. There was no investment in facilities apart from botched-up conversions of toilets. One group of parents attempted to halt the re-organisation by seeking an injunction. It was the middle of August when a judge in chambers ruled that to unpick the re-organisation at that stage would have been more harmful than to let it go ahead. Until then, we didn’t know for certain what awaited us at the start of the autumn term.

Everything happened at break-neck speed. The new school had to be up and running within months. There was no investment in facilities apart from botched-up conversions of toilets. One group of parents attempted to halt the re-organisation by seeking an injunction. It was the middle of August when a judge in chambers ruled that to unpick the re-organisation at that stage would have been more harmful than to let it go ahead. Until then, we didn’t know for certain what awaited us at the start of the autumn term. The vast majority of staff, especially the younger ones, were pragmatic. If they wished to teach in a grammar school, then they had to look towards the independent sector. This was not appealing to many of those who had been educated and had taught in the state system. Staff had to do their utmost, for the sake of all pupils, to make the slit-site system, imperfect though it was, work.

The vast majority of staff, especially the younger ones, were pragmatic. If they wished to teach in a grammar school, then they had to look towards the independent sector. This was not appealing to many of those who had been educated and had taught in the state system. Staff had to do their utmost, for the sake of all pupils, to make the slit-site system, imperfect though it was, work.