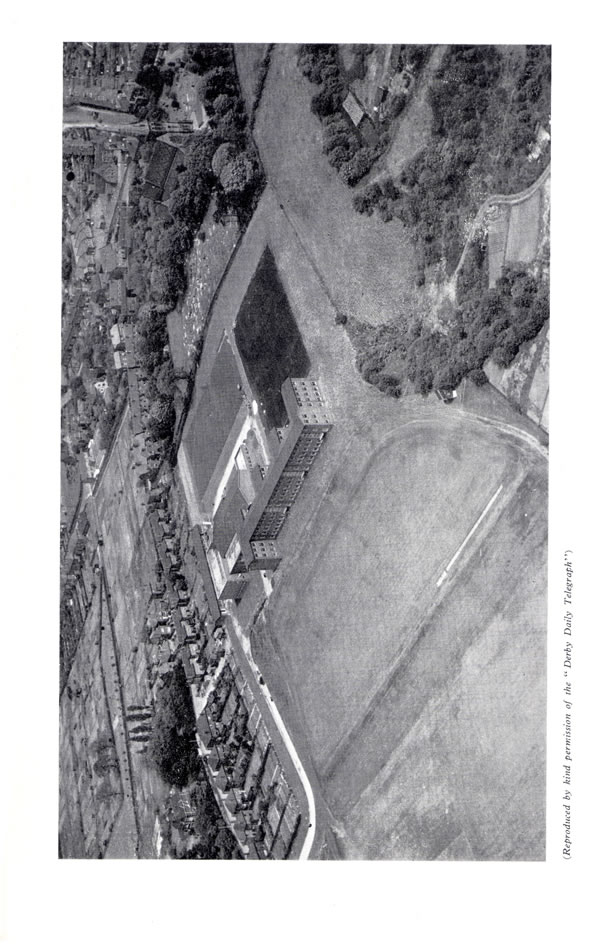

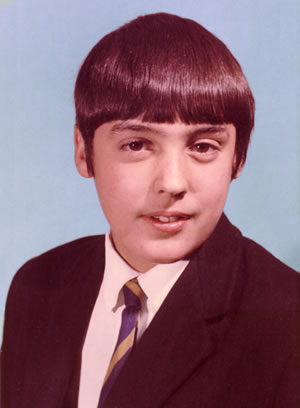

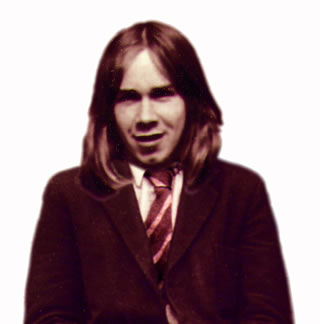

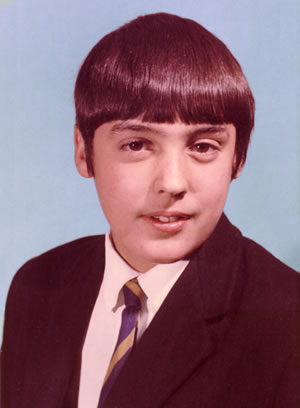

This is the only picture that has survived from my time at Burton Grammar School. I really hate it but, since I have featured a great number of faces of pupils who probably think the same way about theirs, I suppose it is only fair that I should include it.

This is the only picture that has survived from my time at Burton Grammar School. I really hate it but, since I have featured a great number of faces of pupils who probably think the same way about theirs, I suppose it is only fair that I should include it.

I joined the school in 1968 and from fairly early on, it was made fairly clear that if I didn’t achieve “Maths, English and three other ‘O’ Levels”, I was doomed to failure. That, therefore, is exactly what I achieved having opted for science subjects.

I was due to stay on to do Maths and Physics ‘A’ Levels but, due to family circumstances, I instead needed to leave and find employment.

Some of the schoolmasters here enjoyed a glorious career that long preceded my knowing them; in meeting some of them as an adult, it is clear that there was sometimes an underlying irony that went straight over the head of a young boy at school; many of them have passed on and we should “never talk ill of the dead”. Be those things as they may, as with the rest of this website, I want to provide an accurate a record as I can of my time there so I speak as I find… or should I say “found”, many decades ago.

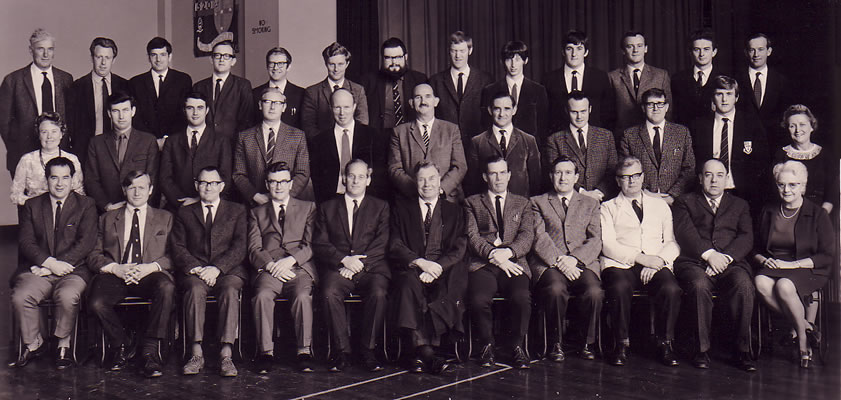

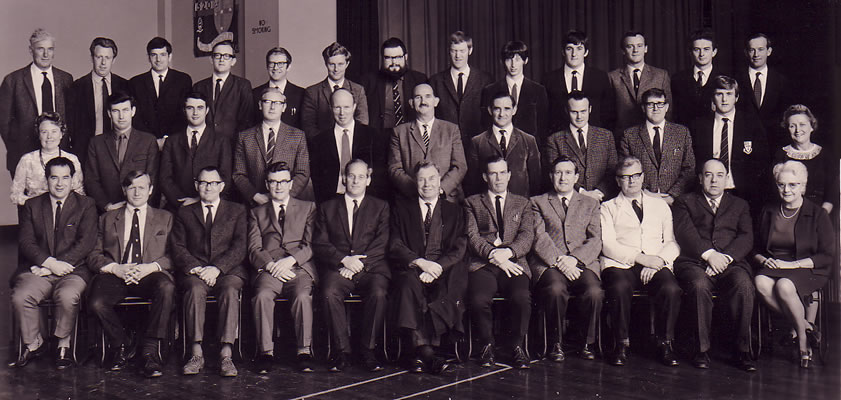

Back Row:

John Andrew (Tinman) – [Metalwork]

‘Tinman’ always seemed to have a certain anger about him. He had deep red veins in his cheeks and when he was having one of his occasional rants, they seemed to glow.

At some point or other, I think most of the class had ducked their head as he bellowed his favourite scorn “Gallagher – you blessed simpleton!!”.

Colin Bagshaw (Bogwash) – [Physics]

Colin was a generally calm and effective teacher. He was my Physics teacher for the whole of my time there and it was always my favourite subject on the timetable. This made the ‘O’ Level a complete breeze with never any doubt that I would pass it without much effort. I am not sure how much of this was down to Mr Bagshaw and how much of it was down to the fact that Physics is just (or was to me anyway), so inherently interesting. Certainly, a school full of teachers like him would make for a very easy passage.

I can remember one slightly amusing anecdote which is nothing to do with school – I used to deliver his daily newspaper to his semi-detached house in Dovedale Close and he was the one person on my round who made me walk back to the pavement and round rather than cut across his lawn.

John Long – [Latin]

I had no contact with Mr Long, nor Latin come to that; he was simply a familiar face.

David Wyatt – [Spanish]

I had to think hard if I actually did Spanish at school, certainly, I can’t count to ten in Spanish which suggests that the brief period for which I took the subject was not particularly arduous.

David was equally wishy-washy leaving a just as scant lasting impression.

John Sneyd – [Physics]

I had nothing to do with John Sneyd, neither for that matter did the rest of the staff seem to. He always seemed a bit of an outsider somehow.

Alan Brewerton (Doc) – [Chemistry]

Doc Brewerton took us for a very brief period, I am not sure if it was even a whole year. He was young and his nickname implied that he was particularly clever though I seem to remember his lessons being pretty dull and humourless.

Robin Langton (Bumble) – [English/Literature]

Bumble didn’t take me for a single lesson. I think his main subject was English Literature which was an ‘options’ subject which I didn’t take. He always seemed very jovial and pretty harmless.

Graham North – [History]

I had absolutely no contact with Graham North and needed help to fill his name in here.

John Armstrong (Louis) – [Maths]

I think Louis was a nice enough chap but completely ‘wet behind the ears’. I am pretty sure it was his first teaching post but generally, he could keep little order and was irresistible to wind up which was an unfortunate combination.

His favourite punishment was rather than dish out 200 lines of 10 words, to award 10 lines of 200 words. The idea only amused him, as a consequence, no one bothered to do them anyway.

He once told us to watch ‘Star Trek’ for homework and to make a note of any occasions where Mr Spock used logic. Unfortunately, my Dad didn’t believe me and wouldn’t let me watch it.

Alan Cure – [Geography]

I had no contact with Alan Cure but he seemed to enjoy very good popularity with those that did.

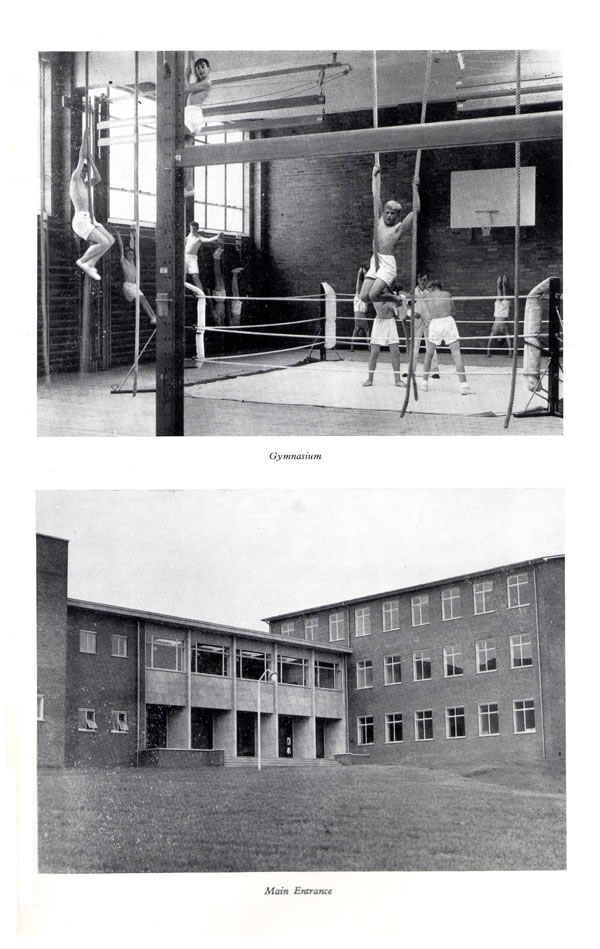

John French (Frenchy) – [PE]

Frenchy always seemed a bit fearsome with a mean one-eyed scowl which I am sure he must have practiced in the mirror. He only ever took us for games or PE and he certainly made me try for brief periods when I felt that his eyes were upon me.

Chris Aylott – [Maths]

I had absolutely no contact with Mr Aylott. Again, I had to have his name filled in here and, when it was confirmed, I had no recollection of it whatsoever.

Michael Green (Ma) – [English/Economics]

Ma took us as a stand in for occasional lessons. In this role, he was a kind of caretaker teacher and used to give us fairly menial things to do, usually read, to get through the lesson without the need to develop any kind of rapport.

Middle Row:

Barningham – [Office]

Just a vaguely familiar face in the office I’m afraid.

M02 & M03

I swear to this day, these two men are complete imposters who snook into the photo because they happened to be in the school, probably for interviews. I don’t have the foggiest idea who they are.

Chris Shepard (Shep) – [English]

Chris Shepard was a pretty good English teacher and in general, I used to enjoy his lessons. It all seemed to turn a bit sour when noises were first heard about the abolition of Grammar schools when it became obvious that he had very ‘left wing’ sentiments not shared by almost the remainder of the staff.

Peter Dawe (Jackdaw) – [Music]

I always thought that Jackdaw’s name was ‘Jack’ so it was a slight shock when it was corrected to Peter; although thinking about it now, with a name like Dawe, who would ever call their son Jack?!

As a music teacher, he was a complete and utter failure. His lessons were totally meaningless and no-one in his classes gained the slightest musical knowledge. He seemed to spend some time with the very small number of pupils that could actually play an instrument already. Aside from that, the only useful aspect of Music lessons was the chance to catch up with a few lines of the ‘I must not run in the corridor’ type.

Harry Smith (Brab) – [Maths]

I didn’t have Brab for a single lesson. I was slightly disappointed by this in some ways because there was the general air that he was an amazingly good teacher and that students of his were automatically assured of high grade results. He was always a very central character with numerous legendary attributes – such as the ability to draw an almost perfect circle with one quick twirl of the elbow.

Harry seemed to enjoy almost unanimous respect from the lowest pupil to the Headmaster.

G. Davis (Taffy) – [Woodwork/Eng.Drawing]

To say that Taffy was quiet was something of an understatement. He would demonstrate how to make a very neat rectangle hole with gentle taps of a mallet on a chisel and then quietly disappear into the woodwork (excuse the pun), leaving us all to hack a piece of wood to death in the vain attempt of imitating him.

Alan White (Chalky) – [English]

I didn’t have Chalky but he did strike me that his lessons might be fun and animated.

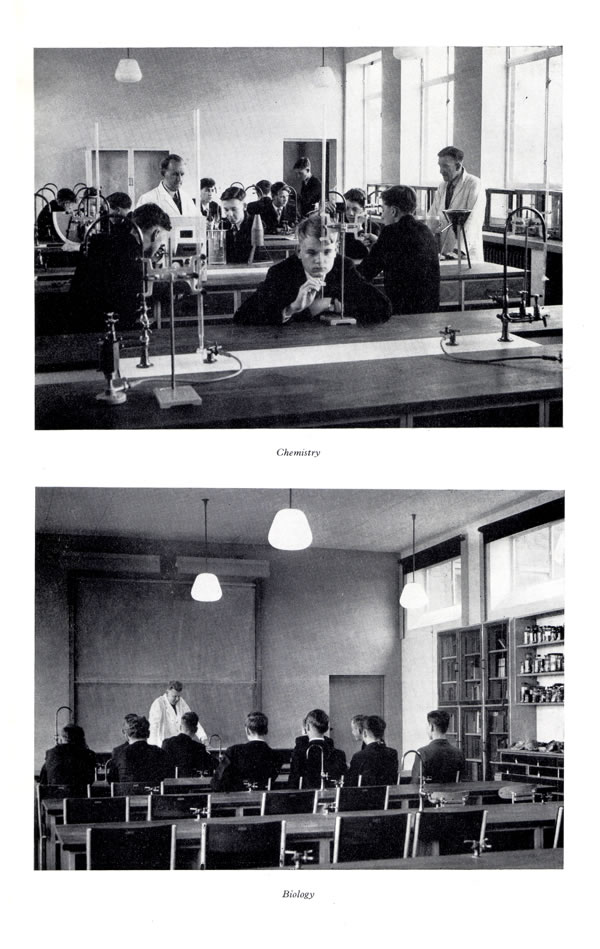

Brian Luckett (Chinner) – [Chemistry]

Brian seemed pretty unique in that he seemed to remember exactly what it was like to be a pupil and almost seemed like he would still like to be one. This had the unfortunate effect that he could generally anticipate most chemical pranks.

Robert James (Jessie) – [French/Latin]

I didn’t have any contact with Mr James but again, he seemed generally popular with everyone who did.

Coates – [Office Secretary]

Just another vaguely familiar face in the office I’m afraid.

Front Row:

Walter Chadbourne (Walt) – [Physics]

I didn’t have any contact with Walt. He only seemed to take lower streams and was probably better known to me as the Scout Leader, not that I was a member. He had a reputation for administering whacks with a gym shoe that I never saw first hand. I was actually very surprised to now learn that he had a longer service with the school than I thought. He always seemed like the Scout Master cajoled into taking a few lessons somehow.

Victor Roebuck (Vic) – [PE/English]

Vic had quite a pleasant manner about him. Firm, but you always knew that he was never really as harsh as he was making himself seem. I think he genuinely enjoyed engaging in sports with boys. I never particularly got on with him because running about on a muddy rugby pitch or, even worse, trudging around sodden farmland was never more than an unfortunately necessary evil to me.

It was actually quite a shock during this project to discover that Vic was such a first class athlete in his day, very narrowly missing out on the Olympic running team.

Ellick Ward (Ernie) – [French]

I didn’t have any teaching exposure to Ernie. I had brief experience of him when I joined the lunchtime ‘Radio Club’ so that I could join others in making a device that could be engineered into a desk to make a faint beeping noise. Four of five of us used to switch them on for a few seconds so that the whole class could delight in watching the masters ears prick up as they wrote on the black-board.

Hugh Wood (Woody) – [French]

Hugh was always friendly and seemed a genuinely nice guy. Unfortunately, his subject was French which no-one ever seemed to have the most remote interest in. Although I never got to take the ‘O’ level, I am actually surprised how much French I almost inexplicably seem to know as an adult which suggests that he was a very effective teacher and that I could have been half-proficient had I been able to muster enough interest.

When the class was noisy, he used to stand and take a pin out of his jacket lapel. We had been conditioned to know that in a few seconds, he was going to drop it and that if its faint ping couldn’t be heard as it hit the floor, the whole class would be in detention.

On one occasion, Chris Borrington deliberately coughed at the crucial moment making everyone groan at him after it was announced that we must all return at the end of school.

Geoffrey Henton (Gaff) – [Geography]

Geoff Henton had an inexplicable air about him. He never shouted – only raised his voice; not once did he ever dish out a single punishment to my recollection, and yet, the moment he entered the room or came into view, there was automatically complete silence and order.

He was a good Geography teacher and I would actually have liked to have taken it as an option but, slightly bizarrely, it was not classed as a science subject so was not available with Biology taking its place.

Bill Gillion (Beak) – [Maths] Headmaster

Bill Gillion was simply the Headmaster was never seen outside of school assembly. I did visit his office on two occasions, neither of them pleasant. On the first, he announced at the end of assembly that someone had been talking the whole way through. He pointed at me and asked me to put my hand up. Though strongly suspecting that I was his quarry, I kept my hand down. His response was to get someone in my vicinity to put their hand up; he then gave instruction, “the boy to his left, put his hand up”, “the boy in front of him put his hand up”; after a few steps, it fell to my turn and when I raised my hand, my heart sank as he announced “Yes, YOU”. I was instructed to report to his study after assembly where I was given a stern telling off. The second occasion was following the fencing accident where a small unsupervised group of us were hacking around with swords outside without wearing face-shields and Robert Whetton was badly injured. I had to go and give my account of the happenings. He did seem a kind, upstanding man though and very worthy Headmaster.

Ron Illingworth (Ronnie) – [Geography]

I had no direct dealings with Ron Illingworth which I must admit, I was slightly relieved about. I always had the impression that he would like to swipe me hard across the back of the head for the sheer pleasure of it. I felt well out of his way but don’t know if he was as fearsome as he seemed.

Norman Jones – [Chemistry]

I didn’t have Norman but he always seemed a pleasant sort.

Raymond Crowther (Joey) – [Biology]

I always thought that Joey was Mr Crowther’s proper name so it was very strange to change his name here from Joseph to Raymond. He was a fairly effective teacher though somehow strangely detached from the rest of the staff. He seemed to spend most of his non-teaching time in a small room at the back of the Biology Lab. I didn’t particularly like Biology though; it was really an imposed subject that I had to do in order to continue with Physics which was my favourite subject.

When the class was unruly, Joey used to stand a chunky table leg up on the front bench and announce something like “Signum Bellum Stat”, which he explained to us was Latin for ‘Symbol of war stands’. This was an indication that the next offender would receive a knock on the head with a wooden baton with a severity (lump size) proportional to the degree of misdemeanour.

I once received the worst punishment, referred to a ‘Crunchie’ as explained below.

Percy Barratt (Butch) – [History]

Percy was another of those familiar characters that ambled around but with whom I had no contact.

Elizabeth Radford (Fanny) – [Divinity/French]

At some point, Mrs Radford seems to have switched from ‘Gertie’ to ‘Elizabeth’ but we only ever really referred to her as Fanny which was always a bit confusing.

Divinity lessons were a complete non-event really. I can only remember pupils being instructed to read a passage from the bible with the constant farce that the next pupil instructed to take over took a while to do so because invariably, no-one but the current reader had got the foggiest idea where the passage was up to.

Questions were sometimes asked at the end with everyone smirking at the hapless victim knowing that his made up answer would be no better than any of theirs.

Missing:

The following masters are not featured in the photo but I did have direct experience of them.

Jack Playll (Pleb) – [History]

Pleb’s history lessons were all comprised as follows: we were given a page range to read from a text book “could you please read pages 112 to 119”. The class would then fall into silence as they armed themselves with elastic bands to flick at one another. Occasionally, when someone made a noise after being caught sharply on the cheek, Jack would look up from his book slightly and cough. And so it went on. Twenty minutes or so later, he would ask questions on the passage we were supposed to have read. It was only a mild dread of being asked a question because a response of “I can’t quite recall the answer sir” simply passed the book to the next person with very little repercussion. To assist things, Mr Playll tended to concentrate his answers on the small minority that were likely to be able to supply an answer and largely left everyone else alone.

He was definitely teaching History for an easy option. He used to heavily tip exam questions to ensure that marks could be easily gained, and wasn’t bothered about ‘O’ levels because most would not take History as an option and those that did would effectively be starting again.

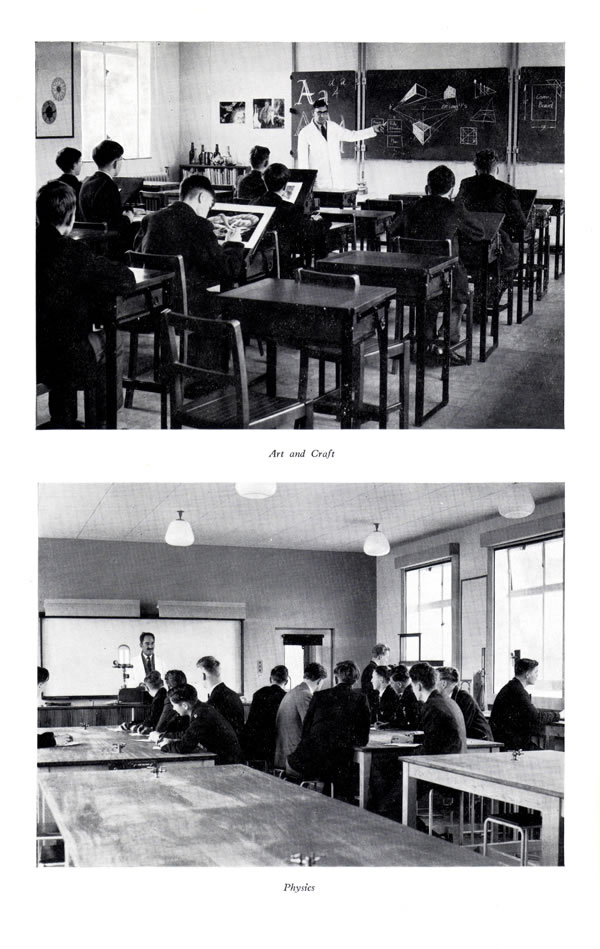

Lewis Heath (Chippy) – [Art]

I quite enjoyed art and Lewis Heath was a decent enough sort of guy. Splodging paint onto paper never really felt like a ‘real’ subject though, particularly since there was no Art ‘O’ level or further ‘lessons’ after the third form, so it always felt like a sort of recreation period for the youngest pupils.

James Moore (Jomo) – [Maths]

Jomo was absolutely legendary! His lessons were a complete riot. He had been persuaded back into service having retired as a local Maths teacher at aged 65, simply because there was a great shortage of maths teachers and the timetable could not be fulfilled.

His maths knowledge seemed such that he wouldn’t be able to pas the ‘O’ level himself and his class control was completely non-existent.

I can remember on one occasion, the adjourning door between classrooms opened and Geoff Henton stuck his head in to find several pupils standing on chairs and an unearthly din. On Gaff’s appearance, everyone immediately sat to silent order; he gave Jomo a sharp look before disappearing again and the class continued with HCFs and LCMs (the ONLY lesson Jomo knew confidently) now much more subdued – but only because of the impending threat from the neighbouring classroom.

David Mart – [Maths]

David Mart started whilst I was at the school but had a much more difficult task on his hands that he could have imagined. He had taken over from Jomo Moore who had firstly, firmly established the culture that Maths was a complete free-for-all and secondly, had left the class quite literally one whole year behind in the syllabus.

To this day, my first lesson with Mr Mart provides me with one of my clearest memories of the school as he very successfully asserted himself where Mr Moore had failed. Maths lessons were suddenly very different with a necessarily increased workload to make up for lost time.

Unknowingly, I had a reasonably strong natural ability for maths. The ‘O’ Level most had once dreaded was completely changed around into one that everyone could take with complete confidence. In a completely unprecedented gesture, I can remember the class collecting all of its tuck-shop money and presenting him with a bottle of wine.

I didn’t find out until this project that David was also an ex-pupil of Burton Grammar School and had attended at both Bond Street and Winshill. By all accounts, he was never a very exceptional student but he turned out to be a very exceptional teacher.

SCHOOL RUGBY

Burton Grammar School had a long and proud tradition of Rugby; “hard and fair play on the sports field to instil a character which carries through to the classroom as a complement to academic success”, and all that. Unfortunately, this was always somewhat lost on me and my memories of the Rugby field may not be entirely typical.

A whole year’s worth of pupils did afternoon sports which usually meant just under ninety pupils. This gave rise to three games. The first, made up of the most impressive thirty, was on the top, carefully tended pitch. The second was on the middle pitch, which was still a very impressive playing surface, inferior to the first only in that it was some distance lower down a steep bank. The third was made up of the rest of the stragglers on the bottom pitch which it would be fair to say, was sometimes ‘quite water-logged’. As you may have already guessed, this included me. I can’t now recall who used to referee the games. Vic and Frenchy took two but I can’t for the life of me remember who used to take the third.

Quite often, there were not quite enough players to make up full teams on the third pitch, sometimes; there was an odd number of players meaning that one side had an extra player, although this was usually in the form of Kenny Mycock which gave little or no advantage. I think it was him I remember one day being adorned in ridiculously ill-fitting spare kit supplied to him after he had tried to forge a letter from his parents to excuse him from the games period for an implausible (and most probably mis-spelled) ailment.

The rules of Rugby were, and remain today, a complete mystery to me. The whistle used to blow, seemingly at random and many of us huddled around in confusion trying to establish whether someone had now got to drop kick the ball or whether we had got to endure another scrum. Almost invariably, it seemed to be the latter which meant, as one of the second-row, I was anticipating getting my ears squashed again, but I didn’t know enough about the rules to question the decision. Neither did I ever really fully understanding the scoring but I learned early in my Rugby career that Mr French did not appreciate the question “Sir, who’s winning?”, so I usually waited until the end of the game where I would try to establish the final score. Not once do I ever recall contributing to it.

Despite my general lack of enthusiasm for the game, it did supply me with some treasured memories. I can remember one occasion in particular, when the field was particularly sodden with one corner being so muddy that to venture onto it meant almost for sure, that ones boots would be completely submerged. The ball plopped down in the middle and shortly afterwards, Frenchy was bellowing at the interested group of pupils standing in a circle around the mud wondering how we were to retrieve it. Frenchy made us all lie on the ground to get covered in mud. “There”, he exclaimed with some satisfaction, “now no-one need worry about getting muddy”. This sparks the memory of another incident were a heavily muddied ball escaped the catch of, I think, Duncan Andrew, and instead bounced off his chest leaving a ball shaped imprint on his previously clean shirt which he then pulled outstretched in front of him and studied it with the disdain that someone might apply to bolognaise sauce being slopped down a best shirt. One more mud anecdote before I move on, some fun was had by sharply kicking ones foot forwards to turn the mud clogged around their boot studs into a muddy projectile to splat on someone’s back. On one occasion, I can recall missing my intended target and instead catching Frenchy on the back of the head. He turned to find out who had dared to throw it; I looked as innocent as possible but was betrayed by a number of traitorous team-mates who were all sniggering in my direction. I was in the middle of trying to explain how it had somehow flown from the bottom of my boot as his sharp slap caught me briskly across the back of the head.

GOOD MEMORIES

Sports Day

I have fond memories of Sports Day. Not for the athletics you understand, ‘Skinny’ Goodwin and myself, being careful not to qualify for any events so that we didn’t have to hare around like demented whippets, devised a much more fun activity.

On Sports days, the steep banks that seperated the different levels of playing field came into play providing a large seating area. Armed with bottles filled with water from the Pavilion, we used to quietly position ourselves a few feet behind a target group, release all of the water and quietly walk away to a spot some distance away from which to observe.

As sure as day, a short while later, the group would instantly spring to their feet feeling their inexplicably wet trousers and we would crack up with as quiet laughter as possible so as not to be discovered.

Bleepers

In the electronics club (run I think by Mr Ward), we made a number of simple bleepers that made a faint bleep when two wires were touched together. These were engineered into around half a dozen desks, well distributed around the form room. At random intervals, the class sniggered as the teacher’s ears pricked up, never quite being able to establish where the faint noises playing for a few seconds were coming from.

Chemical Warfare

Skinny Goodwin found an excellent recipe for ‘nitrogen tri-iodide’, which was a highly explosive powder that could be sprinkled everywhere to produce a loud crack when, for example, a ruler was dropped on it.

The entire stock was eventually confiscated and Chinner Luckett and Doc Brewerton took it to a distant border of the playing fields where they very gingerly disposed of it wearing face masks.

Sledging

I have absolutely no idea where they appeared from but one snowy winter, there was a small fleet of corrigated iron sheets fashioned into sledges with a bent up front and enough space for around four passengers. They were used to hurtle down the bank from the Winshill Church graveyard wall down onto the playground.

It would then be dragged back up and passed to the next waiting team and we would take our place at the back of the queue again.

Unintelligible Questions

There was a short fad where pupils would raise their hand and ask some unintelligible question. When they could stall no longer, the gabble was replaced with a question like “Can I fill my pen please Sir”.

Kudos was gained for a) How long the gabble could be. b) How many times it could be repeated before a proper question was asked. c) The level of fear of the involved teacher (very little for Jomo, maximum points for Gaff Henton).

Army Cadets

I joined the Army Cadet Force with one objective in mind – to fire a gun. I was prompted to join after hearing an account from someone in my class that was already a member that they had spent the previous night on the firing range firing real army guns which was enough to persuade me along.

It turned out to be somewhat duller than I hoped and in fact, .303 rifle shooting was something of a rare treat. Far more time was spent on the playground doing ‘drill’ with Captain Playll shouting (to the best of his ability) “Squad, fa-ace left” whereupon, after the stamping of boots, I would usually end up facing David ‘Numb’ Sherratt wondering which of us was wrong (usually him).

I can remember it being demonstrated how to strip an automatic gun (could be a ‘sten gun’ but don’t quote me) and re-assemble it as quickly and efficiently as possible following which, we all took it in turns. I think the record was around twenty minutes if it could be accepted that the sight was facing the wrong way.

Andrew Bodger seemed to take things seriously and genuinely believe that he was the first line of home defense; thankfully, it was never put to the test.

We spent a few days on an army camp once. My main recollection was getting very comfy on a grass bank with my legs either side of a small mount making a comfortable saddle. The type of gun however, had a much greater recoil than anticipated which brought home most forcibly why this was a very bad idea.

BAD MEMORIES

Fencing Accident

I was a friend of Robert Whetton at Joseph Clark primary school. At the Grammar School, we got split up because he was in the ‘A’ stream, I was in the ‘B’. Though not particularly close friends, I had been to his house in Balmoral Road on numerous occasions. His Mum was always very nice and taught piano. It was there that Robert taught me how to play chess.

I was a friend of Robert Whetton at Joseph Clark primary school. At the Grammar School, we got split up because he was in the ‘A’ stream, I was in the ‘B’. Though not particularly close friends, I had been to his house in Balmoral Road on numerous occasions. His Mum was always very nice and taught piano. It was there that Robert taught me how to play chess.

On this particular day, Mark Osman was playing in the National Schoolboys Rugby Final at Twickernham. Mr Gillion and Mr Henton, all of the games masters and a number of selected pupils had gone on a coach trip to watch.

It was an ‘easy’ afternoon for those of us that remained and a small group of us, including Robert and myself, went outside as a small unsupervised group having decided to do fencing. Although fencing helmets were provided, we didn’t bother wearing them because you couldn’t see through them very well!

In a very unskilful hack around with Robert, my bowed blade somehow flicked off his and hit him in the face. He dropped to the floor and at first, it didn’t seem serious; everyone expected him to get up and laugh it off. However, he didn’t move and vomit began trickling from his mouth. Myself and Steve Goodwin went to report the incident and an ambulance came and took him away.

It transpired that whilst the foil had only inflicted very minor damage, he had hit his head hard on the floor when he fell which had caused brain damage. As a result of the incident, Robert suffered permanent disability. To this day, it has been one of my greatest regrets and I have thought of him countless times. To some extent, this website is dedicated to him.

First Day

On my very first day at Burton Grammar, I turned up very bewildered by it all, with my school cap. In my allotted main corridor cloakroom area, I was approached by Kelvin Russell who tried to snatch the folded cap out of my pocket. I managed to grab it so we both ended up pulling on it. In the stalemate, I was hoping that he would simply let go; instead, he pushed me in the face which caused me to let go and he disappeared up the corridor laughing, throwing it to someone else rugby style.The cap was never seen again and I got a major roasting for losing a garment we could ill afford when I got home. This has always stuck in my mind; it is amazing how much older second year pupils seemed at the time!

Spoiled Blazer

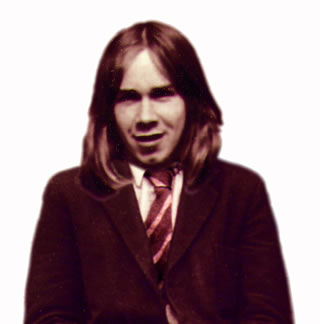

Times were pretty hard at my house, my Dad being a coal-miner in very troubled times. My clothes seemed to have to last much longer than most people’s and were sometimes shabby. I was fairly proud therefore, to be wearing an overdue new blazer.Going upstairs after assembly, I felt a number of firm strokes down my back. When I turned around, John ‘Scabby’ Sharpe (pictured) gestered that he had done it with his finger. After it was pointed out by others however, I took my blazer off to discover that he had drawn chalk marks as hard as possible all over it.My parents were furious, I got a good beating from my Dad and the marks never did come out fully.

Times were pretty hard at my house, my Dad being a coal-miner in very troubled times. My clothes seemed to have to last much longer than most people’s and were sometimes shabby. I was fairly proud therefore, to be wearing an overdue new blazer.Going upstairs after assembly, I felt a number of firm strokes down my back. When I turned around, John ‘Scabby’ Sharpe (pictured) gestered that he had done it with his finger. After it was pointed out by others however, I took my blazer off to discover that he had drawn chalk marks as hard as possible all over it.My parents were furious, I got a good beating from my Dad and the marks never did come out fully.

Cross Country

Myself, Jez Stevens (now living in Carlisle) and someone else from Dalebrook Estate whose name escapes me, skipped cross country a few times by lingering to the back and diverting through ‘winshill dales’ where we used to play in the third boy’s house. At the appropriate time, we went back and re-joined the home runners when there was a suitable gap.On one particular occasion (maybe because someone had grassed), Frenchy stood by a stile at Bladon House Farm ticking names off.When we got back, looking as exhausted as possible, it became obvious that we had been rumbled and we were forced to stay behind and run around the whole school perimeter ten times. Worst of all, I missed my evening paper-round and almost got the sack.

Canoeing

One year, I can remember opting for Canoeing as a summer-time Games activity. I had already conjured up the image of gliding around on the river, jabbing my oar in the water on one side or other to force the boat to sharply turn on my command.

It turned out that we had been suckered; we had to report to the Metalwork room where we discovered that the Canoes were in kit form and our first task was to build them. Now when I say “kit form”, I don’t mean two halves that join neatly together and a seat that clips firmly into place – I mean bales of fibre, cans of resin and uncut lengths of wood.. the sort of thing you would complain bitterly to PayPal about if it had turned up off eBay.

For reasons I don’t now understand, the group was a mixture of pupils from my year and pupils from the next year up, including Keith Large, Robert Large and Stephen Johnson. I always thought that each year did games on a different afternoon.

Summer came and went by which time, we hadn’t managed to construct anything that looked remotely sea-worthy, so we never got to actually experience floating on water.

GOOD/BAD NOT SURE MEMORIES

Methane Bubbles

In the chemistry lab., the benches had twin methane taps for use with Bunsen burners. Chinner used to disappear into the small room at the front of the lab for inordinately long periods which we, correctly or otherwise, referred to as ‘fag breaks’. On one such reprieve, someone behind us was going “Aaahh” and an increasing number of pupils were sniggering as they turned around. I joined them when I saw that someone had lit the tap and had an eighteen inch flame roaring towards him as he rubbed his hands, apparently enjoying the warmth. When the distrurbance grew too loud, it was quickly extinguished when Mr Luckett suddenly appeared at the door to investigate. I seem to be far more concerned about the possibility of a flash-back into the supply as it was turned off now that I was then.

This soon progressed to soap bubbles filled with methane to coax into the air and ignite. Eventually, a large methane bubble was quietly manoeuvred to behind someone’s head; one person tapped him on the shoulder as the other lit it to provide the impression that the world had come to a flaming end. Someone tried the same ploy on me but, now alerted to the possibility whenever we were left alone, I turned to spot the bubble which was just as well because Chinner reappeared forcing the perpetrators to burst it – choking me with methane instead. “Get back to your seats”, ordered Mr Luckett. “Gallagher, why have you turned green?” (I made the last question up).

Crunchie

As indicated above, Joey Crowther used to administer punishment in the form of the whack on the head with a special baton, specially chosen I feel for making the loudest possible ringing tone when a cranium was struck.

I think there were five different degrees, ranging from a light tap to a good strike, depending on the seriousness of the offence. The largest was known as a ‘Crunchie’ which I received on one occasion. It was for flicking something slimy (I think a piece of frog) to startle someone as it landed on their exercise book in front of them. My amusement turned to dread when I faced forwards and saw that Joey had been watching the whole proceedings. I was actually surprised how much it actually hurt and felt that it was close to doing some real damage. It certainly brought tears to my eyes.

School trips

Huh?! I have been slightly surprised to read about the exotic trips to Europe and places. I don’t recall any such opportunities (although I would generally have expected to be in the small group that always got left behind to do lessons because my Dad couldn’t/wouldn’t pay the ten bob).

I have a very vague recollection of a trip with the new drama teacher to a theatre that could have been in Leicester, but was equally possibly Nottingham to see some kind of performance. I can’t recall any singing which probably rules out an Opera; I seem to remember not having a bloody clue what was going on, which suggests it may have been a classic Shakespeare play; and I have no recollection of any laughs so it was probably not one of his better works.

CONCLUSION

There are generally strong sentiments that it was a grave government mistake to abolish Grammar Schools, and in some ways, so it was. Comparing my account of the school to much earlier ones however, I get the feeling though, that the ‘rot had already set in’. One of the key indicators of this I feel was the discontinuance of Class 5X.

For a short period in the nineteen-sixties, Burton Grammar School enjoyed one of its finest hours. It was a period of strong Oxford/Cambridge success and an overall academic success that out-performed nearby Repton School – one of the most esteemed Private Schools in the country. Due to enormous pressures, Mr Gillion however, he had to abandon his thoughts of Academic excellence by the top stream of pupils, leaving the lower streams with much less attention. Instead, the reverse was imposed – to bolster a National average deficiency, there was a shift in ethos to making sure that as many pupils as possible received the ideal of five good pass ‘O’ levels. The brighter students could achieve that with much less guidance.

Gone was the overall feeling of great aspiration by those that had it within their grasp; instead, there was the much diminished feeling that everything was geared to trying to ensure that as many as possible got the requisite five ‘O’ levels, ideally including the most esteemed Maths and English, anything above that was a bonus.

True, I got my ‘Maths, English and three others’ which provided me with the minimum requirement for some Higher Education, but I was never one of the pupils that shone – it was they who really suffered.

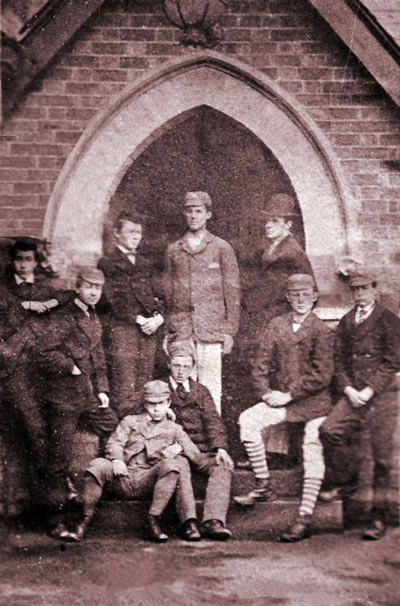

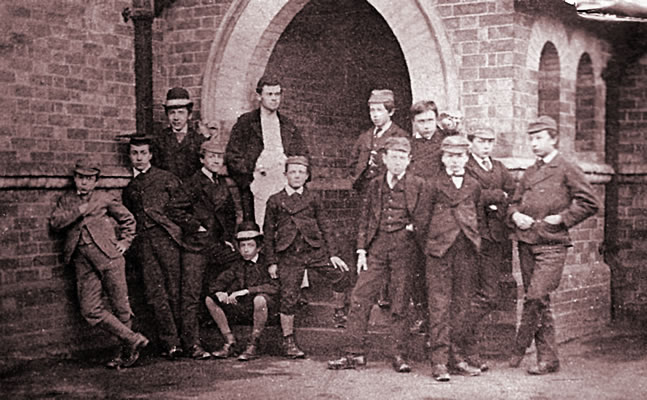

I was at the school from 1945 to 1951 and in many ways the final year was the happiest of the whole time. For various reasons, mainly due to the fact that the minimum age for sitting the new GCE was 16, I repeated a year in the 5th form known as 5CII. It was there I made two very good friends, whom I’m happy to say, I still meet even now, namely Ray Gilbert (shown here with Frank on the right) and Peter Booth, whom we knew at ‘Banty’. It was also a happy year because I was familiar with the syllabus, plus a set of very fine masters, i.e. Ellick Ward for French, ‘Bomber’ Jones for History, Mr Snape, whom we referred to as the Humber Super Snape, ‘Butch’ Barrett for Religion, Norman Jones Chemistry and last, but by no means least, dear Harry Smith for Physics and Maths. Incidentally, Harry taught me for one year at Derby Tec’ for A-level Geometry and I can remember quite well when he put the alternative segment theory on the blackboard. “Come on Toon, you should know this,” was his remark. One never forgot his way of teaching us Fundamental Principles including the method for learning sines, cosines and tangents; i.e. ‘Percy Has Bought His Penny Bun’ for ‘perpendicular, hypotenuse and base’ or when we got on to what he called Ladies’ Maths, i.e. perms and combs. Lastly, when he dictated geometry homework, we would have a rectangle Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog.

I was at the school from 1945 to 1951 and in many ways the final year was the happiest of the whole time. For various reasons, mainly due to the fact that the minimum age for sitting the new GCE was 16, I repeated a year in the 5th form known as 5CII. It was there I made two very good friends, whom I’m happy to say, I still meet even now, namely Ray Gilbert (shown here with Frank on the right) and Peter Booth, whom we knew at ‘Banty’. It was also a happy year because I was familiar with the syllabus, plus a set of very fine masters, i.e. Ellick Ward for French, ‘Bomber’ Jones for History, Mr Snape, whom we referred to as the Humber Super Snape, ‘Butch’ Barrett for Religion, Norman Jones Chemistry and last, but by no means least, dear Harry Smith for Physics and Maths. Incidentally, Harry taught me for one year at Derby Tec’ for A-level Geometry and I can remember quite well when he put the alternative segment theory on the blackboard. “Come on Toon, you should know this,” was his remark. One never forgot his way of teaching us Fundamental Principles including the method for learning sines, cosines and tangents; i.e. ‘Percy Has Bought His Penny Bun’ for ‘perpendicular, hypotenuse and base’ or when we got on to what he called Ladies’ Maths, i.e. perms and combs. Lastly, when he dictated geometry homework, we would have a rectangle Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog.

This is the only picture that has survived from my time at Burton Grammar School. I really hate it but, since I have featured a great number of faces of pupils who probably think the same way about theirs, I suppose it is only fair that I should include it.

This is the only picture that has survived from my time at Burton Grammar School. I really hate it but, since I have featured a great number of faces of pupils who probably think the same way about theirs, I suppose it is only fair that I should include it.

I was a friend of Robert Whetton at Joseph Clark primary school. At the Grammar School, we got split up because he was in the ‘A’ stream, I was in the ‘B’. Though not particularly close friends, I had been to his house in Balmoral Road on numerous occasions. His Mum was always very nice and taught piano. It was there that Robert taught me how to play chess.

I was a friend of Robert Whetton at Joseph Clark primary school. At the Grammar School, we got split up because he was in the ‘A’ stream, I was in the ‘B’. Though not particularly close friends, I had been to his house in Balmoral Road on numerous occasions. His Mum was always very nice and taught piano. It was there that Robert taught me how to play chess. Times were pretty hard at my house, my Dad being a coal-miner in very troubled times. My clothes seemed to have to last much longer than most people’s and were sometimes shabby. I was fairly proud therefore, to be wearing an overdue new blazer.Going upstairs after assembly, I felt a number of firm strokes down my back. When I turned around, John ‘Scabby’ Sharpe (pictured) gestered that he had done it with his finger. After it was pointed out by others however, I took my blazer off to discover that he had drawn chalk marks as hard as possible all over it.My parents were furious, I got a good beating from my Dad and the marks never did come out fully.

Times were pretty hard at my house, my Dad being a coal-miner in very troubled times. My clothes seemed to have to last much longer than most people’s and were sometimes shabby. I was fairly proud therefore, to be wearing an overdue new blazer.Going upstairs after assembly, I felt a number of firm strokes down my back. When I turned around, John ‘Scabby’ Sharpe (pictured) gestered that he had done it with his finger. After it was pointed out by others however, I took my blazer off to discover that he had drawn chalk marks as hard as possible all over it.My parents were furious, I got a good beating from my Dad and the marks never did come out fully.