Friars Walk School

Select page to view:

Related History:

|

|

It is not certain when it first came into being but there was a ‘school house’ on the site of the Friars Walk school in 1824. At that time, it was a large single classroom with a dwelling house on one side and stable on the other; it also had its own small garden. It stood next to the graveyard that served a church which occupied almost the same position as the current Saint Modwen’s church, which was itself built to replace part of the derelict Abbey.

The house at one time housed a schoolmaster but, by this time, it was no longer fit for such purpose. It was instead rented to a poor person and the schoolmaster rented a house in High Street, as did the usher – the only other member of staff.

In the early eighteen thirties, the aforementioned Parish Church needed a classroom to accommodate its Sunday school. The trustees were approached about building one but it was decided, given that the building would only be needed on a Sunday, the best proposition would be to extend the school building so that it could be used on weekdays.

The project grew to a complete, major, renovation in conjunction with the extension and including a new schoolmaster house. The plans were for the three gabled brick Tudor house more or less as it appears today.

In 1834, the extensive renovation was completed, much of the cost being borne by the church. The cost of the renovation was £600!

Thankfully, the building is sufficiently small to make it viable for modern commercial use. The right-hand section was the masters house, the left-hand section was the stables leaving the centre section for the school itself for around sixty pupils.

Colourized reproduction (by me) of drawing by Buckler, 1830, of Friars Walk building in its

former heyday before eventually being renovated to form the ‘new’ Grammar School.

January 2008 photo following recent renovation work in order

that building could be preserved as a commercial property.

At some point, to suit the new usage after ceasing

as a school, the main doorway was relocated.

In the early nineteenth century, when photography was very much in its infancy, drawings and etchings were far more available than photographs. In 1860, Rock Brothers and Payne published a collection of etchings depicting scenes around Burton upon Trent, produced in the late 1850s by G.H. Newbold.

This rare plate titled ‘Church & Grammar School, Burton on Trent’ shows the view from Stapenhill of Saint Modwens Church and the Burton Grammar School some 20 years before Bond Street School was built.

The ‘Silverway’ branch of the river Trent, a branch off which was used by the school for swimming lessons, is today little more than a brook and the view is completely obscured by trees.

In 1861, the government set up the Clarendon Commission to inquire into public schools and make recommendations about the needed changes, in particular, any reform required to broaden education from ‘classic’ to ‘modern’ subjects such as mathematics, science, history and modern languages. In 1864, this was followed by the Taunton Commission (named after the chairman Baron Henry Taunton, not the town!) to inquire into grammar schools.

This involved a school visit from assistant commissioner, T.H.Green who made an inspection of all grammar schools in Staffordshire. Below is his report of Burton Grammar School in September 1865.

BURTON FREE GRAMMAR SCHOOL

Headmaster: Rev. Henry Day, LL.B.

Usher: Henry Hodson

In 1861, the government set up the Clarendon Commission to inquire into public schools and make recommendations about the needed changes, in particular, any reform required to broaden education from ‘classic’ to ‘modern’ subjects such as mathematics, science, history and modern languages. In 1864, this was followed by the Taunton Commission (named after the chairman Baron Henry Taunton, not the town!) to inquire into grammar schools.

This involved a school visit from assistant commissioner, T.H.Green who made an inspection of all grammar schools in Staffordshire. Below is his report of Burton Grammar School in September 1865.

The grammar school at Burton consists of two departments. At the time of my examination, there were 26 boys in the upper department and 48 in the lower. All the boys in the upper department were learning Latin, and more than half of them Greek. English grammar and analysis, French, geography and English history, as well as arithmetic, are attended to. Considering the number of subjects taught and the age of the boys, I thought the standard of this department satisfactorily high. There were only four boys turned 14. These together formed the 1st and 2nd classes. Two of them translated for me on paper 20 lines from the First Iliad, which they had been reading, with only one serious mistake each, and with considerable general neatness and accuracy. Exactly the same may be said of a translation which the same boys did from the First AEneid. Two others did a very fair translation from Caesar. The 3rd class, however, forms the hope of the school, consisting mostly of boys about the age of 12. These did translations from Ovid’s Heroides for me, both on paper and viva voce, in a way that showed a very careful grounding.

In arithmetic six boys of the upper department did the most difficult sums I could set them quickly and correctly. The rest were not so advanced, but what they did was generally done correctly.

I examined the upper four boys also in history and the analysis of Goldsmith’s “Traveller.” In history they were not positively deficient, but their knowledge did not seem fresh. In English analysis they seemed as well up as need be.

The whole upper department, I understood, did a written examination every Saturday morning. The result of this appeared in the neatness with which they did work on paper. Their writing I thought generally good, and their spelling and grammar were correct.

The lower department seemed inferior all round. Many of the boys in it were very young, and apparently of very humble parentage, who had scarcely yet learned to read properly. The upper classes did decently in history and geography, and both their ordinary writing and their writing from dictation were pretty good. The arithmetical standard I thought scarcely so high as it ought to be. Very few of the boys attempted the more difficult sums that I set them; what they attempted, however, they generally did correctly. The general tone of the school, so far as I could see and hear, was good.

The school building is very unsatisfactory for the purpose. It consists of two long, low rooms, the upper of which is used as the ordinary schoolroom, the lower as a class room. The ventilation is bad, and the offices not in a proper state. There is no playground, not even a yard, nor any house for the master. The school adjoins the churchyard, and is low and damp in situation. A man likely to know told me that he could recall 16 boys who had been taken from the school within three years on account of the situation.

On the whole, if the number of boys in the three higher classes of the upper department were more in proportion to the population and wealth of the town, the state of the school, as compared with others, might be reckoned satisfactory. As it is, the size of the upper department (which, however, had risen from 17 to 26 in a year and a quarter) scarcely suffices to justify the state of the lower.

The population of the town is supposed to be nearly 20,000, and for several years it has been eminently prosperous. On the Marquis of Anglesey’s property there, land for 500 new houses had been let during the six months previous to my visit. The magnates of brewery, of course, live in country houses elsewhere, but there are a good many professional men in the town, and a large number of men who get incomes of £500 a year and upwards as managers in the breweries. This part of the middle class seems as yet to make very little use of the grammar school, though perhaps more than it did, while on the other hand the temptation of lucrative employment at the breweries draws all the boys from the school at the age of 14.

The absence from the school of those boys who ought to fill its upper department I heard accounted for chiefly on two grounds: (1.) The professional and more respectable mercantile men objected to the mixture of their sons with those of a lower class; an objection which the separation of departments and the imposition of a £7 annual fee on boys in the upper one, established in 1858, have not yet removed. (2.) The grammar school, with its bad building and situation, could not compete with the attractions of cheap boarding schools. I also heard it stated that the head master, whose ability as a teacher all acknowledge, was thought scarcely to give enough of his time to the school.

The transfer of the school to a new building, with proper residence for the master and playground, in the suburbs would do a great deal to make it more popular with the middle class. Land for this purpose could, I believe, be readily obtained, and the feoffees of the town charities are said to have large accumulations, from which they have given freely to the elementary schools of the town. If, in addition to a new building, scholarships could be provided, tenable either at the Burton school itself, or at some other having better means of providing an education for the universities, the general character of the school, and with it the educational prospects of all the boys in the town, might be greatly raised.

Digest of Information

FOUNDATION AND ENDOWMENT. – By William Bean, Abbot of Burton Monastery, who, in 1520 built and gave money in trust for endowment of a schoolhouse for a free grammar school. Earliest deed in existence is a conveyance to trustees of land for benefit of school, dated 10th June 1745. Further endowment of £3 per annum for master and £6 for usher in 33 Eliz. (1590-1) by Elizabeth Paulett, out of a rentcharge of £10 on lands in Clerkenwell in Middlesex.

SCHOOL PROPERTY. – Farm at Breaston containing 112 acres, and another at Orton-on-the-Hill containing 120 acres. Also £187 3s.3d consols derived from sale of land to railway; and £333 6s.8d consols, called “Clerkenwell house dividends.” Annual income £452 gross, £439 net, all applied to purposes of school. Site good. Building inferior.

OBJECTS OF TRUST. – The maintenance of a free grammar school and schoolmaster in the town of Burton.

For all boys between the ages of eight and 16 years, of parents resident in the parish being able to read and write and knowing the first four rules of arithmetic, with a preference to longest residence. All (except five in each school, selected from poor as a reward for scholarship and good conduct) to pay capitation fees, viz. £7 for upper school, and for boarders and non-resident day scholars in lower school,£2 for day boys at lower school(scheme 1858).

SUBJECTS OF INSTRUCTION PRESCRIBED. – In the upper school, English, Latin, Greek, French, and German, arithmetic, mathematics, history, and geography. In the lower school, English and Latin grammar, with exercises and translation, elements of French, writing and arithmetic (with special reference to commercial rules), with rudiments of modern geography, and modern history (scheme 1858).

GOVERNMENT AND MASTER. – Scheme approved by Court of Chancery 2nd August 1858.

The trustees, 15 in number, appointed by the Court of Chancery, manage the school property subject to the scheme, appoint and dismiss the masters,and visit school. Head master required to be a member of the Church of England and a graduate of an English university. Head master has the internal regulation of the school. Cannot hold other preferment.

State of School in Second Half-year of 1864

GENERAL CHARACTER. – Classical. In age of scholars, third grade.

MASTERS. – Head master receives fees, and pays from them assistant masters and French masters. Of the surplus he retains two thirds for his own use. Total income from endowment £270 from fees £25. Usher, £140 from endowment, and may take boarders.

DAY SCHOLARS. – 74, from distances up to three miles. Upper school, 5 free; 29 paying £7 a year. Lower school, 5 free; 35 paying £2 a year.

BOARDERS. – A few boarders been with the master since Michaelmas 1866. (8th January 1868). Terms £60 to £70 per annum. Four meals a day. Meat once at least. Each boy has a separate bed. Boys rise at 7.00 a.m. and go to bed at 9.20 p.m.

INSTRUCTION, DISCIPLINE, ETC. – At admission must read and write and know the first four rules of arithmetic.

School classified by one leading subject chiefly.

School course modified to suit particular cases.

Scripture lesson Sunday for boarders. Day boys prepare lesson at home for Monday. Boys taught Bible and Church Catechism. Monitors appointed sometimes to assist in instructing the junior classes.

Promotion by marks, and examination held at Christmas by head master and at Midsummer by examiner appointed by trustees.

Marquis of Anglesey gives prizes of books to value of £5.

Punishments: caning on the hand in public and impositions.

No playground. No gymnasium. Drilling taught in summer.

School time 40 weeks per annum. Study from 28 to 30 hours per week.

The grammar school at Burton consists of two departments. At the time of my examination, there were 26 boys in the upper department and 48 in the lower. All the boys in the upper department were learning Latin, and more than half of them Greek. English grammar and analysis, French, geography and English history, as well as arithmetic, are attended to. Considering the number of subjects taught and the age of the boys, I thought the standard of this department satisfactorily high. There were only four boys turned 14. These together formed the 1st and 2nd classes. Two of them translated for me on paper 20 lines from the First Iliad, which they had been reading, with only one serious mistake each, and with considerable general neatness and accuracy. Exactly the same may be said of a translation which the same boys did from the First AEneid. Two others did a very fair translation from Caesar. The 3rd class, however, forms the hope of the school, consisting mostly of boys about the age of 12. These did translations from Ovid’s Heroides for me, both on paper and viva voce, in a way that showed a very careful grounding.

In arithmetic six boys of the upper department did the most difficult sums I could set them quickly and correctly. The rest were not so advanced, but what they did was generally done correctly.

I examined the upper four boys also in history and the analysis of Goldsmith’s “Traveller.” In history they were not positively deficient, but their knowledge did not seem fresh. In English analysis they seemed as well up as need be.

The whole upper department, I understood, did a written examination every Saturday morning. The result of this appeared in the neatness with which they did work on paper. Their writing I thought generally good, and their spelling and grammar were correct.

The lower department seemed inferior all round. Many of the boys in it were very young, and apparently of very humble parentage, who had scarcely yet learned to read properly. The upper classes did decently in history and geography, and both their ordinary writing and their writing from dictation were pretty good. The arithmetical standard I thought scarcely so high as it ought to be. Very few of the boys attempted the more difficult sums that I set them; what they attempted, however, they generally did correctly. The general tone of the school, so far as I could see and hear, was good.

The school building is very unsatisfactory for the purpose. It consists of two long, low rooms, the upper of which is used as the ordinary schoolroom, the lower as a class room. The ventilation is bad, and the offices not in a proper state. There is no playground, not even a yard, nor any house for the master. The school adjoins the churchyard, and is low and damp in situation. A man likely to know told me that he could recall 16 boys who had been taken from the school within three years on account of the situation.

On the whole, if the number of boys in the three higher classes of the upper department were more in proportion to the population and wealth of the town, the state of the school, as compared with others, might be reckoned satisfactory. As it is, the size of the upper department (which, however, had risen from 17 to 26 in a year and a quarter) scarcely suffices to justify the state of the lower.

The population of the town is supposed to be nearly 20,000, and for several years it has been eminently prosperous. On the Marquis of Anglesey’s property there, land for 500 new houses had been let during the six months previous to my visit. The magnates of brewery, of course, live in country houses elsewhere, but there are a good many professional men in the town, and a large number of men who get incomes of £500 a year and upwards as managers in the breweries. This part of the middle class seems as yet to make very little use of the grammar school, though perhaps more than it did, while on the other hand the temptation of lucrative employment at the breweries draws all the boys from the school at the age of 14.

The absence from the school of those boys who ought to fill its upper department I heard accounted for chiefly on two grounds: (1.) The professional and more respectable mercantile men objected to the mixture of their sons with those of a lower class; an objection which the separation of departments and the imposition of a £7 annual fee on boys in the upper one, established in 1858, have not yet removed. (2.) The grammar school, with its bad building and situation, could not compete with the attractions of cheap boarding schools. I also heard it stated that the head master, whose ability as a teacher all acknowledge, was thought scarcely to give enough of his time to the school.

The transfer of the school to a new building, with proper residence for the master and playground, in the suburbs would do a great deal to make it more popular with the middle class. Land for this purpose could, I believe, be readily obtained, and the feoffees of the town charities are said to have large accumulations, from which they have given freely to the elementary schools of the town. If, in addition to a new building, scholarships could be provided, tenable either at the Burton school itself, or at some other having better means of providing an education for the universities, the general character of the school, and with it the educational prospects of all the boys in the town, might be greatly raised.

Digest of Information

FOUNDATION AND ENDOWMENT. – By William Bean, Abbot of Burton Monastery, who, in 1520 built and gave money in trust for endowment of a schoolhouse for a free grammar school. Earliest deed in existence is a conveyance to trustees of land for benefit of school, dated 10th June 1745. Further endowment of £3 per annum for master and £6 for usher in 33 Eliz. (1590-1) by Elizabeth Paulett, out of a rentcharge of £10 on lands in Clerkenwell in Middlesex.

SCHOOL PROPERTY. – Farm at Breaston containing 112 acres, and another at Orton-on-the-Hill containing 120 acres. Also £187 3s.3d consols derived from sale of land to railway; and £333 6s.8d consols, called “Clerkenwell house dividends.” Annual income £452 gross, £439 net, all applied to purposes of school. Site good. Building inferior.

OBJECTS OF TRUST. – The maintenance of a free grammar school and schoolmaster in the town of Burton.

For all boys between the ages of eight and 16 years, of parents resident in the parish being able to read and write and knowing the first four rules of arithmetic, with a preference to longest residence. All (except five in each school, selected from poor as a reward for scholarship and good conduct) to pay capitation fees, viz. £7 for upper school, and for boarders and non-resident day scholars in lower school,£2 for day boys at lower school(scheme 1858).

SUBJECTS OF INSTRUCTION PRESCRIBED. – In the upper school, English, Latin, Greek, French, and German, arithmetic, mathematics, history, and geography. In the lower school, English and Latin grammar, with exercises and translation, elements of French, writing and arithmetic (with special reference to commercial rules), with rudiments of modern geography, and modern history (scheme 1858).

GOVERNMENT AND MASTER. – Scheme approved by Court of Chancery 2nd August 1858.

The trustees, 15 in number, appointed by the Court of Chancery, manage the school property subject to the scheme, appoint and dismiss the masters,and visit school. Head master required to be a member of the Church of England and a graduate of an English university. Head master has the internal regulation of the school. Cannot hold other preferment.

State of School in Second Half-year of 1864

GENERAL CHARACTER. – Classical. In age of scholars, third grade.

MASTERS. – Head master receives fees, and pays from them assistant masters and French masters. Of the surplus he retains two thirds for his own use. Total income from endowment £270 from fees £25. Usher, £140 from endowment, and may take boarders.

DAY SCHOLARS. – 74, from distances up to three miles. Upper school, 5 free; 29 paying £7 a year. Lower school, 5 free; 35 paying £2 a year.

BOARDERS. – A few boarders been with the master since Michaelmas 1866. (8th January 1868). Terms £60 to £70 per annum. Four meals a day. Meat once at least. Each boy has a separate bed. Boys rise at 7.00 a.m. and go to bed at 9.20 p.m.

INSTRUCTION, DISCIPLINE, ETC. – At admission must read and write and know the first four rules of arithmetic.

School classified by one leading subject chiefly.

School course modified to suit particular cases.

Scripture lesson Sunday for boarders. Day boys prepare lesson at home for Monday. Boys taught Bible and Church Catechism. Monitors appointed sometimes to assist in instructing the junior classes.

Promotion by marks, and examination held at Christmas by head master and at Midsummer by examiner appointed by trustees.

Marquis of Anglesey gives prizes of books to value of £5.

Punishments: caning on the hand in public and impositions.

No playground. No gymnasium. Drilling taught in summer.

School time 40 weeks per annum. Study from 28 to 30 hours per week.

At the end of the commission came a sort of ‘yesteryear OFSTED report’ providing a comparison of all Staffordshire grammar schools. There were 22 such schools at this time, unfortunately, for some reason there are no results for Tamworth, Leek, Dilhorne or Cannock Grammar Schools. It is though, an invaluable picture that paints a thousand words.

Maths was probably the most feared of all GCE ’O’ Levels. It is hard to believe looking at this example now how it could have created any level of dread!

If you are slightly confused by the lack of Calculus – there were two Joint Matriculation Syllabuses, ‘A’ and ‘B’. The latter, shown here, was for Secondary Modern schools that allowed GCE examination. Grammar Schools took Syllabus ‘A’ which also included differentiation, integration, curve-fitting and maxima/minima (dy/dx = 0).

Latin was only taken by the ‘A’ Stream so, as a ‘B’ Stream pupil, I managed to escape this particular delight.

In September 1907 I entered Burton Grammar School as a new boy, and even in those days there was talk of a new school, to be erected finally in 1957. As a small boy fresh from a tiny village school the buildings at Bond Street seemed palatine, although the manual room downstairs, and the Art room, biology room and staff room upstairs were not added till after my departure in 1911.

My previous education had taken place in one large room, in which different classes, for children of various ages were held. So I found it easy to get lost in the multiplicity of rooms at the Grammar School. The first day I was there I strayed into the wrong classroom and it was sometime before my unwanted presence was discovered. And if the grandeur of the buildings oppressed me, I was awed by the appearance of the masters in their gowns and mortar boards.

Few Scholarships

In those days the number of minor scholarships granted by the Education Authorities was extremely small. I believe that only four per annum were granted by the Education Committee at Burton, tenable at the Grammar School. I know for certain that only two scholarships tenable at the Grammar school were granted by the Derbyshire Education Committee. I remember this very well indeed, for I was placed 3rd out of 527 candidates from various schools in the county and the other entrant from Bretby School obtained seventh place. But a Swadlincote boy obtained a higher place, and the Bretby boy was not granted a scholarship. As he had done so well, however, Derbyshire Education Committee, after some pressure, granted him a scholarship tenable at a school in Derby, to which he had to travel each day from Bretby.

Scholarship Boys

At the Grammar School there was a distinction between “scholarship boys” and those whose parents paid for their education. As a rule the former came from poorer homes and were not so well-dressed, but the masters made no discrimination, and the majority of fee-paying boys were tolerant, though there were a few little snobs. Probably the latter were envious for usually the scholarship boys displayed a brighter intellect, though not all of them made the grade. On the first day of each term, an official from Talbot & Co. – a partner in the firm being Clerk to the Goveners – attended the school with a Gladstone bag in which to put the money, and a book of receipts. Each fee-paying boy stepped forward in turn, and handed over £3 6s. 8d., in cash, for there were no Treasury notes in those days.

No School Meals

There were no facilities for a hot meal at mid-day. Those boys who lived a long way from school brought their mid-day meal with them, and ate it in the school yard if the weather was fine, or in the Assembly Hall when it rained. There was no school tuck shop, but buns, lemonade and sweets could be obtained at a shop, which consisted of the front room of a cottage, opposite the school, in Bond Street. At a later date a new shop was built a little further down the street. But pennies were scarce in those days, and few of us were regular patrons.

There were a few “boarders” at the school, i.e. pupils who stayed at the Headmaster’s house throughout the term, and were looked after by the Headmaster’s Aunt. Two masters – the Rev. J. Mills and A. Rigby – who lived some distance away usually had their midday meal with the boarders.

Sporting Activities

Attendance at cricket or football was voluntary, and boys who like myself lived at some distance from the school, were not expected to attend, but any keen boy soon found his place. Wednesday and Saturday afternoons were devoted to sport, attendance at school on Saturday mornings being compulsory. There was a miniature rifle range in a shed in the playground where on certain evenings, after school hours, it was possible to obtain practice in shooting under the supervision of a master. Similarly there were facilities for swimming in the River Trent near the Stapenhill end of the Ferry Bridge. One evening a week after school hours there was half an hour’s physical training with dumbbells under the supervision of Sergeant Micky Maher. During the dinner hour, rough and tumble games of football were played in the school playground.

No Uniform Dress

There was no attempt at uniformity in dress. The only distinguishing mark of a Burton Grammar School boy was his cap, which was marked with alternate bands of red and blue, each band one inch in width. These caps were conspicuous at a distance, and any boy infringing a rule was careful to take off his cap before doing so! There were no school badges, and no prefects’ insignia, for the good reason that there were no prefects! The school was not divided into houses, and there was no school magazine since the ‘Cygnet’ had temporarily stopped, although a boarder named Drewry and myself tried to start one a new one, by carefully writing out the ‘copy’ and using a gelatine bed. I believe it ran for about half-a-dozen issues!

‘Dickie’ Robinson - Headmaster

In 1907 there were 134 boys at the school, and the staff consisted of the Headmaster and eight assistant masters, Even in those days space was limited, and not infrequently two, and sometimes three masters would teach at the same time in the Assembly Hall, which could be divided into three “rooms” merely by pulling curtains across.

The Headmaster, Mr. R. T. Robinson, M.A., B.Sc., was affectionately known as ‘Dickie’. He had a fierce bristling moustache of the type favoured in after years by R.A.F. officers. But his fierce expression was belied by a twinkle in his eye, and my four years at school laid the foundation of a lasting friendship which lasted until his death. He was just and impartial, and had the knack of imparting mathematical knowledge which stirred the dullest intellect. On occasion he did not hesitate to inflict corporal punishment. Such an incident being a rare occurrence had the greater effect upon the school.

‘Piggy’ Jeffcott - Second Master

The senior assistant master was W.T. Jeffcott, B. A., known to generations of boys as ‘Piggy’. Stout of body, ponderous in movement, and sporting a ragged yellow moustache, his brain was keen and alert, and it was a very smart boy indeed who contrived to bluff him. His particular subject was Latin, and with experience gained over many years he had reduced teaching to an art. He seemed to know instinctively what questions would appear on an examination paper, and any boy who was prepared to work benefited greatly, but a shirker felt the lash of his sarcasm.

Rev. ‘Nitty’ Mills

Another interesting character was the Rev. James Mills, who was irreverently nicknamed “Nitty”. His lean, stooping figure was garbed in clerical black or dark grey, and he had a neat grey beard. His watchful eyes immediately detected any slackness in class, and his favourite punishment was an entry in the “black book”. Three entries in this book caused the culprit to forfeit a half-holiday, and subsequent entries led to an interview with the Headmaster. Of all the masters, Nitty was the most frequent user of the book, and if it was not in its usual place in the drawer of the desk in the Assembly Hall, any master needing it would send a boy to see if Mr. Mills was using it!

‘Strongy’ Storer

Probably the most popular master was ‘Strongy’ John Storer. Small and slight in build, with a ragged

moustache, Strongy had a pair of twinkling grey eyes which missed little that went on. His subjects were chemistry with the higher forms (IV B upwards), and Natural History with the lower forms. The latter subject was his favourite and my regret I had collated Chemistry with him instead of Natural History. But we became great friends, and many specimens from his collection and in the school Biology laboratory were obtained by me. Our friendship continued long after I left school, and we enjoyed many rambles together.

‘Theta’ Rigby

And then there was the lean dark figure of Arthur Rigby, B.Sc., noted for his sarcastic remarks. His main subject was Physics, and he was nicknamed ‘Theta’ because he frequently used this symbol to denote a rise or fall of temperature during his lessons. Subsequently he became Headmaster of Coalville Grammar School. It was he who gave me my only entry in the Black Book. In practical Physics we worked in pairs, and my partner, a boy called Adams, burned the bottom out of a calorimeter. Theta was very annoyed and gave Adams an entry in the Black Book. Then, turning to me, he said, “I’m going to give you two entries, Wain. Always remember, when you have a fool for a partner, you’ve got to watch him!”

‘Pecky’ Pecquintot

The French master in those days was a Swiss named Pecquinot and nicknamed ‘Pecky’. He possessed prodigious strength, and his favourite trick was to take a batch of impositions, and tear them across repeatedly, displaying a strength of wrist and fingers I have never seen equalled. If he caught a boy not attending to him, he would seize the culprit by his ears and lift him out of his seat saying, “Ach, I will pull your cabbage-leaf for you!” Pecky spoke several languages and once confessed that Welch was the hardest to learn.

Two other masters were the Headmaster’s brother ‘Taffy’, and ‘Paddy’ Wood.

‘Tommy’ Stevenson

‘Tommy’ Stevenson was concerned with the lower forms and I never had a lesson under him. His burly form and twinkly eyes concealed a hidden sense of humour. He was a bachelor, living in lodgings and on one occasion when he was ill, two of his colleagues went to see him. “Front room upstairs”, said his landlord after they had introduced themselves. Pushing open the door, the visitors saw a mound of bed-clothes on top of which lay a wreath. “Good Lord!”, said one of them, “she might have said that he has passed away”. Then a voice boomed out from the bed, “Pleased to see you fellows”. “What is the meaning of this?”, they queried. “Oh, I felt a bit low so I sent for a wreath and lay there admiring it. I feel much better now”. And he duly recovered.

John F. Rose

On one occasion, John Rose who lived in Stapenhill came over the Ferry Bridge on his way back from school lunch. A sudden rainstorm caught him unprepared and he was wet through when he arrived back at the school. As he entered the Assembly Hall, he was spotted by the Headmaster. “Ah Rose”, he said, “you look wet, come along with me”. He took him across to the headmaster’s house and rigged him out with a spare suit of plus fours. John was a fairly big man but with the kneebands of the plus fours fastened around his ankles, he presented a startling appearance which fascinated the school for the rest of the afternoon. He was very glad to change back into his own clothes at the end of the day which had been dried for him.

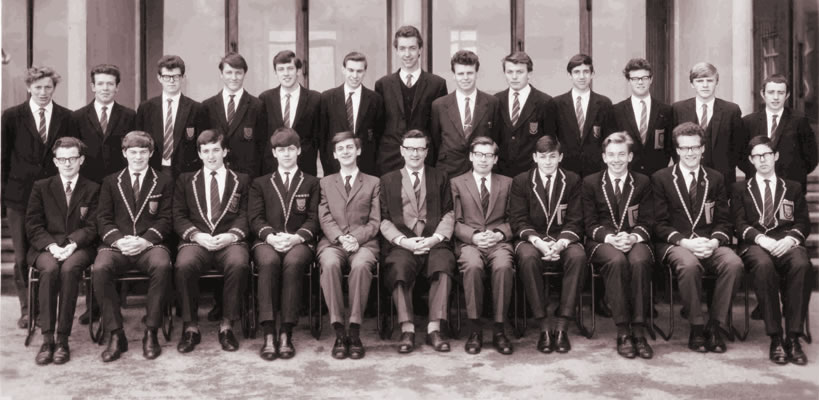

Back Row: Brian Taylor, Alex Pratt, B03, David Nutt, Whitewood, Johnstone, Peter Wallis, Shirley, Deakin, B10, B11, Boulton, Bristow

Front Row: F01, Goodhead, Alan Cure, Redfern, M.E. Smith, Hugh ‘Woody’ Wood (Form Master), R.W. Smith, Rees, Badcock, Rose, F10